Valerian has a calming effect on both townie and tourist.

Dear friends:

Our town modestly celebrated its 250th anniversary last year. I say modestly because we know we can’t take the credit for all that history, but we are surpassingly grateful for it.

Around the world small towns, small churches, and small schools are caretakers of a rich heirloom seed-bank of viable human values that have been tested for thousands of years, long before the first city appeared. We are keeping alive some very old, very vigorous strains of community life that will one day be desperately needed to inoculate and heal the diseases of venality, violence, materialism, and meaninglessness that have infected the human race and are making it mortally ill. These heirloom seeds of community life are beginning to find their way into post-modern awareness with an ironic twist, showing just how radical conservatism can be.

Illustrations by Candice Hutchison

The ancient tribal council that evolved into the church and town meeting, lo and behold, is now touted as an innovative form of “participatory democracy.” The ageless value of thrift, with its motto, “Waste not, want not,” is updated into the 21st century as “economy of scale.” The old aphorism of our great-grandparents: “Use it up, wear it out, make it do, or do without,” is now put forth as a trendy “voluntary simplicity.” The tribal hunting ground or pasture that evolved into the village common is now presented as a “green zone” or a “land trust.” Ancestral places of worship are now called “voluntary spiritual communities” and “faith-based organizations.” Old-fashioned natural home remedies are resurrected as “alternative medicine.” The volunteer fire department is now raised up under the rubric of “volunteerism.” The perennial potluck public supper to which everyone brings what they can and eats all they want, with the leftovers sent home with someone who needs them, is now hailed as “cooperative local economy.” The old practice of getting your eggs, milk, meat, and vegetables from your garden and your neighbors is now touted as “community-based agriculture.” And yet, small towns and villages have been doing these things forever. It’s very old, very good, and very simple, really.

Illustrations by Candice Hutchison

The ancient tribal council that evolved into the church and town meeting, lo and behold, is now touted as an innovative form of “participatory democracy.” The ageless value of thrift, with its motto, “Waste not, want not,” is updated into the 21st century as “economy of scale.” The old aphorism of our great-grandparents: “Use it up, wear it out, make it do, or do without,” is now put forth as a trendy “voluntary simplicity.” The tribal hunting ground or pasture that evolved into the village common is now presented as a “green zone” or a “land trust.” Ancestral places of worship are now called “voluntary spiritual communities” and “faith-based organizations.” Old-fashioned natural home remedies are resurrected as “alternative medicine.” The volunteer fire department is now raised up under the rubric of “volunteerism.” The perennial potluck public supper to which everyone brings what they can and eats all they want, with the leftovers sent home with someone who needs them, is now hailed as “cooperative local economy.” The old practice of getting your eggs, milk, meat, and vegetables from your garden and your neighbors is now touted as “community-based agriculture.” And yet, small towns and villages have been doing these things forever. It’s very old, very good, and very simple, really.

Field and forest report, mid July

The more delicate spring flowers have faded at the coming of the heat, making way for the tougher high-summer blooms of black-eyed Susan, Queen Ann’s lace, magenta fireweed, and sweet-smelling valerian.

The valerian, also called “heliotrope” in these parts, is a gift to the harried native and the frenzied rusticator alike. Its dreamy, soporific odor has a calming effect on both townie and tourist, leading them to forget what it was they were so anxious about just a moment ago. For centuries, valerian root has been recognized as an herbal remedy for anxiety. It is no wonder that the modern pharmaceutical Valium is derived from this plant.

More natural and un-natural events, early May

Motherhood is a most natural event, and war is a profoundly un-natural event.

Julia Ward Howe is best known for her stirring Civil War hymn “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” which she wrote after the first battle of Bull Run in 1861, when many thought the war was glorious and would end in a few weeks. But after watching four years of that brutal War Between the States leaving two-thirds of a million dead and millions maimed, as well as the nearly 200,000 killed in the Franco-Prussian War, Julia Ward Howe had a profound change of heart.

Town report

We offer our thanks to our road commissioner, who is given the onerous task of upgrading the town’s roads and bridges just when they are most heavily used. With plowing and salting occupying crews during the winter, improvements must be done in summer. Patience is the watchword for all concerned.

Freshwater report, mid July

Green frogs and bullfrogs call from the ponds, while snapping turtles ever so slowly cross the roads, seeking suitable places to lay their eggs. Give them the right of way; they have earned it by being here first, by several million years.

Natural events, late July

Ramblers around town or along the shore these days soon discover fallen feathers of crows or gulls or other fowls of the air, gifts from the sky. This is molting season for adult avians, the time when old feathers are replaced by new, usually after brooding and while food is still abundant. If you are like me, it is hard to pass up a recently dropped feather; it is an exquisite treasure of natural design and construction begging to be taken home.

Field and forest report, mid July

The more delicate spring flowers have faded at the coming of the heat, making way for the tougher high-summer blooms of black-eyed Susan, Queen Ann’s lace, magenta fireweed, and sweet-smelling valerian.

The valerian, also called “heliotrope” in these parts, is a gift to the harried native and the frenzied rusticator alike. Its dreamy, soporific odor has a calming effect on both townie and tourist, leading them to forget what it was they were so anxious about just a moment ago. For centuries, valerian root has been recognized as an herbal remedy for anxiety. It is no wonder that the modern pharmaceutical Valium is derived from this plant.

More natural and un-natural events, early May

Motherhood is a most natural event, and war is a profoundly un-natural event.

Julia Ward Howe is best known for her stirring Civil War hymn “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” which she wrote after the first battle of Bull Run in 1861, when many thought the war was glorious and would end in a few weeks. But after watching four years of that brutal War Between the States leaving two-thirds of a million dead and millions maimed, as well as the nearly 200,000 killed in the Franco-Prussian War, Julia Ward Howe had a profound change of heart.

Town report

We offer our thanks to our road commissioner, who is given the onerous task of upgrading the town’s roads and bridges just when they are most heavily used. With plowing and salting occupying crews during the winter, improvements must be done in summer. Patience is the watchword for all concerned.

Freshwater report, mid July

Green frogs and bullfrogs call from the ponds, while snapping turtles ever so slowly cross the roads, seeking suitable places to lay their eggs. Give them the right of way; they have earned it by being here first, by several million years.

Natural events, late July

Ramblers around town or along the shore these days soon discover fallen feathers of crows or gulls or other fowls of the air, gifts from the sky. This is molting season for adult avians, the time when old feathers are replaced by new, usually after brooding and while food is still abundant. If you are like me, it is hard to pass up a recently dropped feather; it is an exquisite treasure of natural design and construction begging to be taken home.

Our fire chief and gifted amateur bird carver, Denny Robertson, was marveling recently about the immensely complicated structure of even the simplest feather. Not only do they have a stem and veins like a leaf, but each vein has feathery edges, too, so that they lock together in flight. On owls the leading edges of the wing feathers are soft and downy, allowing the birds to fly in silence. Ducks and sea birds have an oil gland that helps them groom their feathers so water rolls off the duck’s back, literally.

A fallen feather taken home becomes a talisman tying us in with the rest of Creation. Native people have used feathers for ornamentation for millennia. So did Victorian ladies. Even my mother’s generation wore feathery hats to church or when traveling, though they didn’t molt all that much.

While adult birds are shedding, the young are fledging. Last year we watched a crow’s nest in the big sugar maple behind the town hall for a couple of months, the adults faithfully feeding their fledglings for weeks on end. Then, about this time last year, the end of their labors drew near; it was time for flying lessons in the orchard. Awkward, squawking youngsters bumbled about trying out their new feathers, still white at the base. Flapping frantically, they careened from the oak tree into the branches of a lilac bush, then blundered into an apple tree, groaning and griping but obviously elated, while the parents cawed encouragement.

Meanwhile, down behind the dam on the mill brook, fledgling mallards paddled along behind their mothers, preening and looking over their shoulders, admiring their fluffy new coats.

Field and forest report, late July

While the birds of the air are earning their wings, the beasts of the field and forest are sending their young forth to an uncertain future. It’s heart-breaking to see how many young mammals become road-kill, though we know that far more survive.

If you hit an animal or see one in the road, couldn’t you stop and put it off to the side in the long grass if it is dead? If it is alive and might survive, contact your nearest animal rehabilitator. If it must be put out of its misery, a sharp blow to the head may suffice as the ultimate act of mercy. Then you will become a member of the order of St. Francis, the saint who ministered to the birds and the beasts, and they all will honor you.

Rank opinion II

We are slowly remembering what the ancients knew well: that every creature is kin. We have relatives wherever we look and wherever we go. We never need be alone or lonely again. We are daily invited to one great, wild family reunion. All we have to do is say yes to the invitation, and start getting to know everyone again.

More seedpods to carry around with you

From Bernd Heinrich: “We are social animals. We like to feel a part of something of beauty and power that transcends our insignificance. It can be a religion, a political party, a ball club. Why not also Nature?”

From Annie Dillard: “We are here to witness the creation and to abet it.”

And a final one from Woody Guthrie: “If you play more than two chords, you’re showing off.”

That’s the almanack for this time. But don’t take it from us—we’re no experts. Go out and see for yourself.

Our fire chief and gifted amateur bird carver, Denny Robertson, was marveling recently about the immensely complicated structure of even the simplest feather. Not only do they have a stem and veins like a leaf, but each vein has feathery edges, too, so that they lock together in flight. On owls the leading edges of the wing feathers are soft and downy, allowing the birds to fly in silence. Ducks and sea birds have an oil gland that helps them groom their feathers so water rolls off the duck’s back, literally.

A fallen feather taken home becomes a talisman tying us in with the rest of Creation. Native people have used feathers for ornamentation for millennia. So did Victorian ladies. Even my mother’s generation wore feathery hats to church or when traveling, though they didn’t molt all that much.

While adult birds are shedding, the young are fledging. Last year we watched a crow’s nest in the big sugar maple behind the town hall for a couple of months, the adults faithfully feeding their fledglings for weeks on end. Then, about this time last year, the end of their labors drew near; it was time for flying lessons in the orchard. Awkward, squawking youngsters bumbled about trying out their new feathers, still white at the base. Flapping frantically, they careened from the oak tree into the branches of a lilac bush, then blundered into an apple tree, groaning and griping but obviously elated, while the parents cawed encouragement.

Meanwhile, down behind the dam on the mill brook, fledgling mallards paddled along behind their mothers, preening and looking over their shoulders, admiring their fluffy new coats.

Field and forest report, late July

While the birds of the air are earning their wings, the beasts of the field and forest are sending their young forth to an uncertain future. It’s heart-breaking to see how many young mammals become road-kill, though we know that far more survive.

If you hit an animal or see one in the road, couldn’t you stop and put it off to the side in the long grass if it is dead? If it is alive and might survive, contact your nearest animal rehabilitator. If it must be put out of its misery, a sharp blow to the head may suffice as the ultimate act of mercy. Then you will become a member of the order of St. Francis, the saint who ministered to the birds and the beasts, and they all will honor you.

Rank opinion II

We are slowly remembering what the ancients knew well: that every creature is kin. We have relatives wherever we look and wherever we go. We never need be alone or lonely again. We are daily invited to one great, wild family reunion. All we have to do is say yes to the invitation, and start getting to know everyone again.

More seedpods to carry around with you

From Bernd Heinrich: “We are social animals. We like to feel a part of something of beauty and power that transcends our insignificance. It can be a religion, a political party, a ball club. Why not also Nature?”

From Annie Dillard: “We are here to witness the creation and to abet it.”

And a final one from Woody Guthrie: “If you play more than two chords, you’re showing off.”

That’s the almanack for this time. But don’t take it from us—we’re no experts. Go out and see for yourself.

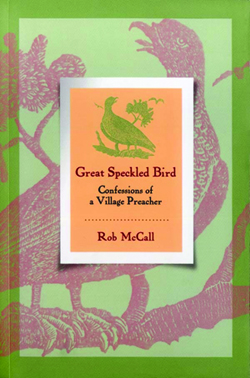

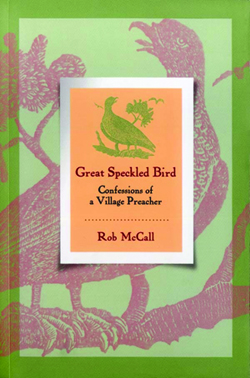

Rob McCall is a journalist, naturalist, and fiddler, and pastor of the First Congregational Church of Blue Hill, Maine UCC. This column derives from his weekly radio show on WERU, 89.9 FM, Blue Hill and 99.9 Bangor. The author’s latest book, Great Speckled Bird: Confessions of a Village Preacher (Pushcart Press), is available through your local bookstore. Readers can contact him directly via e-mail: awanadjoalmanack@gmail.com or post a comment using the form below.

Illustrations by Candice Hutchison

Illustrations by Candice HutchisonI am out to sing songs that will prove to you that this is your world and that if it has hit you pretty hard and knocked you for a dozen loops, no matter what color, what size you are, how you are built, I am out to sing the songs that make you take pride in yourself and in your work. —Woody Guthrie

Rank opinion I

This could be dismissed as nostalgia for a forgotten past, except for one undeniable fact: There are hundreds of thousands of small towns and villages world-wide still holding to, fighting for, and thriving with their ancient conservative radical values, still striving to provide a good life for their children and elders, still leaving their houses unlocked, still in touch with their neighbors, still carrying on through the ages, through war and peace, through the rise and fall of great cities and empires, through drought, famine, fire, flood, panic, boom, and bust.

After the family, the village is the oldest human institution on earth. And today there are thousands of disenchanted urban and suburbanites flocking to these shrines of ancient wisdom for the well-being of themselves and their children. Many have found, and will find, a calling to labor daily in local agriculture, churches, schools, and town government in these small nurseries of human well-being, our truest insurance into the future.

A seedpod to carry around with you

From Joyce Dennys: “Living in a small town...is like living in a large family of rather uncongenial relations. Sometimes it’s fun, and sometimes it’s perfectly awful, but it’s always good for you. People in large towns are like only children.”

Field and forest report, mid June

The dandelions have gone by, and the orange and yellow hawkweed, buttercups, red and white clover, and ox-eye daisies are taking over. In the woods, the wild viburnum, sometimes called “high-bush cranberry,” shows its rosettes of white flowers. Ornamental viburnums are also in bloom. These handsome shrubs produce berries that feed many birds during the winter; there is no sight like a flock of whispering cedar waxwings descending onto these fruitful bushes come winter.

The wild viburnum is often attacked and defoliated by the viburnum beetle in two stages, first by the grub and later in the season by the adult beetle. I do not know of any organic control for these pests, but would like to hear of some. If you must spray, pyrethrins are probably the least toxic.

Natural events, late June

The pace of lawn mowing slows a little now due to generally drier weather, but most of us will still be out there at least once a week making a huge racket, blowing fumes, increasing our carbon footprint, and pulverizing innocent green living things.

America has a lawn fetish, and you’d better have one, too, or risk being shunned as un-American. Your commentator, despite all his high talk, is out there mowing with the rest of them. Mea culpa, mea culpa.

My theory is that the lush, close-cut greensward harkens back to Neolithic times when we were herders and when wide-open spaces grazed close to the ground spelled security and happiness for our ancestors. All of this mowing is done by the ancient ghost of Man the Herder and Man the Farmer mindlessly trying to return to those days of yore when we really did grow our own food, which is now produced largely by distant agribusinesses subsidized by our tax dollars.

Natural events, mid July

In many parts of our great and vast country the heart of summer brings heat and drought, and with them, wildfires and wilting crops. The effect has been amplified in recent years by Earth’s warming climate (doubters of which by now ought to be embarrassed for themselves). As with so many other things, we along the Maine coast have escaped these devastations so far. We wake to cooling fog from warm moist air moving over the cool waters of the Gulf of Maine, and we retire to the cool calm of dusk or to flashes of lightning and the deep drumming of distant thunder.

We are into the generally hottest and muggiest days of the summer season. These days have the beneficial effect of driving the last vestige of winter’s cold from the very marrow of our bones and pushing its hardships out of mind for a time. The heat seems to be good for moths and butterflies, as we count tiger swallowtails, viceroys, and monarchs, as well as many smaller varieties. Some lucky observers might be able to report luna moths, the silent spirits of the summer night. The Lepidoptera tend to fluctuate in numbers in an eight- to eleven-year cycle. Some years they may seem to have disappeared entirely, then a few years later they are back in considerable numbers.

Yr. mst. hmble & obd’nt servant,

Rob McCall

Rob McCall is a journalist, naturalist, and fiddler, and pastor of the First Congregational Church of Blue Hill, Maine UCC. This column derives from his weekly radio show on WERU, 89.9 FM, Blue Hill and 99.9 Bangor. The author’s latest book, Great Speckled Bird: Confessions of a Village Preacher (Pushcart Press), is available through your local bookstore. Readers can contact him directly via e-mail: awanadjoalmanack@gmail.com or post a comment using the form below.

Magazine Issue #

Display Title

Awanadjo Almanack

Secondary Title Text

Welcome to Blue Hill: the Town, the Bay, the Mountain

Sections