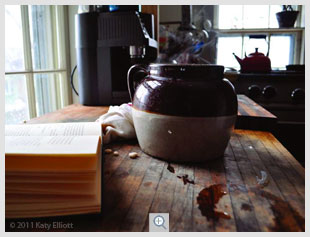

A while ago we tackled the making of a proper chowder. This time we take on baked beans. As usual, we welcome your comments.

Nearly all New Englanders of a certain age and generations back grew up eating baked beans often, usually once a week. Most likely the beans were paired with boiled frankfurters, but codfish cakes weren’t excepted. The basic technique for baking beans was the same—you had your ingredients, your bean pot, and your heat source (an oven or a fire pit)—but there were no end of variations depending on your taste or how your mother did it and, no doubt, her mother before. The Maine novelist Kenneth Roberts, a traditionalist who could get as weepy-eyed over a plate of baked beans as he could over the bedrock democracy of an old-style New England town meeting, especially loved his grandmother’s beans. “Ah me!” he wrote in The Kenneth Roberts Reader. “Those Saturday night dinners of baked beans, brown bread, cottage cheese, Grandma’s ketchup.... “My grandmother’s beans were prepared like this: Four cupfuls of small white beans were picked over to eliminate the worm-holed specimens and the small stones that so mysteriously intrude among all beans, then covered with water and left to soak overnight. Early the next morning, usually around five o’clock, they were put in a saucepan, covered with cold water, and heated until a white scum appeared on the water. They were then taken off the stove, the water thrown away, and the bean pot produced. “In the bottom of the bean pot was placed a one-pound piece of salt pork, slashed through the rind at half-inch intervals, together with a large peeled onion; then the beans were poured into the pot on top of the pork and onion. On the beans were put a heaping teaspoon of mustard, half a cup of molasses, and a teaspoon of pepper; the bean pot was filled with boiling water, and the pot put in a slow oven. “At the end of two hours a tablespoon of salt was dissolved in a cup of boiling water and added to the beans. Every hour or so thereafter the cover was removed and enough boiling water poured in to replace that which had boiled away. To add large amounts of water—to fill the pot to the top and let it boil down to the beans before adding more—meant that the beans would be greasy and wholly lacking in the fruity richness of properly cooked beans. An hour before suppertime the cover was taken off for good and no more water added. Thus the pork, in the last hour, was crisped and browned, and the top layer of beans crusted and slightly scorched.”“My mother made baked beans every Saturday when I was growing up,” says Eileen, who is of a much later era than Kenneth Roberts’s grandmother but is still somewhat of a traditionalist. “I remember hating them. I didn’t learn to like beans until I began making them for my own family.”

Everyone who has had a plateful of Eileen’s best—even those who heretofore have claimed to dislike baked beans—acknowledge how spectacular they are. Tender, they are neither soggy nor hard; flavorful, they are not overly sweet; bursting with goodness, they are surrounded by an ambrosial sauce that...

Enough, enough! Let us get on with it. Here is her recipe:

Eileen’s Baked Beans

Ingredients:

1 1/2 lbs dried “small white beans,” or navy beans, or pea beans approximately 3/4 -pound chunk of salt pork with some lean meat in it 1 small peeled onion approximately 1/2-cup molasses mixed with 1 tsp dry mustard salt and pepper Pick over the beans carefully to remove any stones, then wash in clean water and drain. In a pan, cover the beans with fresh water and soak over night. The next morning, cut the rind from the pork, cut the pork into small pieces, drain the beans, and start layering the ingredients in a large traditional bean pot. Begin with a layer of beans, add a few pieces of pork, sprinkle lightly with salt and pepper, and drizzle with molasses. Add another layer and then bury the onion in the middle. Continue layering. Be sure the pork in the last layer is buried in beans. Add boiling water until all of the beans are covered. Bake at 300 degrees for 4 to 5 hours. After 2 hours have passed, top up with boiling water and keep adding boiling water every hour or so to keep the beans from drying out. During the last 30 to 40 minutes, stop adding water and remove the cover. Taste to see if the beans are cooked through.

Ingredients:

1 1/2 lbs dried “small white beans,” or navy beans, or pea beans approximately 3/4 -pound chunk of salt pork with some lean meat in it 1 small peeled onion approximately 1/2-cup molasses mixed with 1 tsp dry mustard salt and pepper Pick over the beans carefully to remove any stones, then wash in clean water and drain. In a pan, cover the beans with fresh water and soak over night. The next morning, cut the rind from the pork, cut the pork into small pieces, drain the beans, and start layering the ingredients in a large traditional bean pot. Begin with a layer of beans, add a few pieces of pork, sprinkle lightly with salt and pepper, and drizzle with molasses. Add another layer and then bury the onion in the middle. Continue layering. Be sure the pork in the last layer is buried in beans. Add boiling water until all of the beans are covered. Bake at 300 degrees for 4 to 5 hours. After 2 hours have passed, top up with boiling water and keep adding boiling water every hour or so to keep the beans from drying out. During the last 30 to 40 minutes, stop adding water and remove the cover. Taste to see if the beans are cooked through.

Steamed Boston Brown Bread

Ingredients:

1 scant teaspoon baking soda 2/3 cup molasses 1 cup yellow cornmeal 1 cup flour 1 cup sweet milk 1/2 teaspoon salt

Ingredients:

1 scant teaspoon baking soda 2/3 cup molasses 1 cup yellow cornmeal 1 cup flour 1 cup sweet milk 1/2 teaspoon salt

Stir baking soda into molasses until dissolved. Combine all ingredients in 2 buttered 1-pound metal baking-powder cans [or something similar]. Steam in a covered kettle, keeping water at the same level for 3 hours. Fill cans three-quarters full of batter to allow for expansion of bread. Open cans and allow bread to cool and dry before taking it out. Cut across.

B&M

Thicker sauce, darker beans

No visible salt pork

Sweeter (heavy on the molasses)

Bush

Thinner sauce, lighter beans

Some visible salt pork

Sweet, but not too sweet

Finally, how can one discuss beans without mentioning ... er... um... gas? One can’t. Song, story, anecdote, joke—even arguably the most famous ditty of all (“Beans, beans, the musical fruit...”)—they all celebrate that certain gas produced by eating baked beans.

According to the best scientific data, the deal is this: Beans contain high levels of a complex sugar that can be difficult to digest. The small intestine can’t handle the sugar, so it is passed on to the large intestine. There, various bacteria go to work. The byproduct is carbon dioxide, hydrogen, and methane. The result is a memorable gift from an even more memorable meal.

Magazine Issue #

Display Title

Mainely Gourmet: Favorite Baked Beans

Sections