Evinrude, Bishop & Strange: The inventor, the adventurer, and the artist

Remembering those who have influenced how we respond to boats, ships, and the sea—we continue our series of short biographical sketches.

Thanks to Ole’s invention,

Thanks to Ole’s invention,

Bess can get her own ice cream.

(He was a sly one, that Ole.) ©CorbisOle Evinrude

Father of the outboard motor industry

There’s a story about Ole Evinrude that, while possibly apocryphal, has a nice ring to it. One summer day in 1906, Evinrude was picnicking on an island in a Wisconsin lake with his fiancée Bess. It was hot—90 degrees in the shade—and Bess mentioned that she sure could go for some ice cream, so Evinrude, the romantic, rowed some five miles round trip to satisfy her hankering. During that pull it dawned on him that there might be an alternative to grunting and sweating in the hot sun over a pair of oars. He went back to his shop and began tinkering with a machine that could be clamped to a boat’s transom and propel it forward.

Evinrude had the skills for the job. An expert machinist and patternmaker, he was co-owner of Clemick & Evinrude, a company that specialized in building custom engines. In a year’s time he had developed what is generally considered to have been the first practical, reliable gasoline-powered outboard motor—single-cylinder, two-cycle, 11⁄2-horsepower, iron-block engine, with a starting crank hitched to a heavy flywheel. Two years later he and a partner founded the Evinrude Motor Company.

Born in Norway, Ole Evinrude (1877-1934) emigrated with his family in the early 1880s to a farm in Wisconsin, where he spent his childhood. (His birth name was Ole Andreassen Aaslundeie; later, in America, he took the surname Evinrude after his mother’s family farm in Norway.) He showed an aptitude for practical engineering as a young man, self-taught at first and then gaining hands-on experience as a machine-shop apprentice. He would then spend several years honing his skills in several mid-western machine-tool companies before opening the Clemick & Evinrude shop.

In 1914, with his outboard dominating the new industry, Evinrude sold his half interest in the Evinrude Motor Company, but that wasn’t the end of his pioneering work. His goal was to develop a more powerful, lightweight outboard, something that would be more portable than the early models were. By 1919 he had perfected what he called the Evinrude Light Twin Outboard—a two-cylinder, two-cycle, 3-horsepower aluminum motor that weighed only 48 pounds—and established a new company named Elto after it. Eventually, years later, Elto would become the core of OMC, the Outboard Marine Corporation, and Ole Evinrude would be seen as the father of the outboard motor industry.

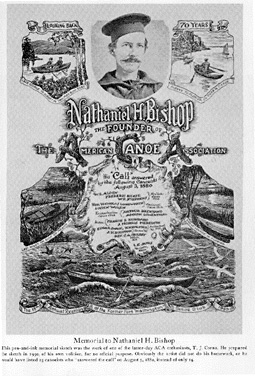

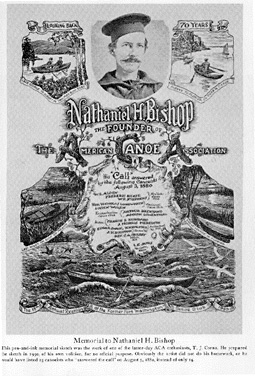

Memorial to Nathaniel H. Bishop.

Memorial to Nathaniel H. Bishop.

©T.J. Cornu/A.C.ANathaniel Holmes Bishop

An American pioneer

Small-boat adventuring became something of a craze on both sides of the Atlantic during the Victorian age. Enthusiasts took to the waterways in all sorts of tiny craft—rowboats, canoes, daysailers—that before then were considered unsuitable for anything beyond taking an afternoon spin on a tranquil stream. The man who kicked it all off was John Macgregor, an Englishman who popularized the decked double-paddle canoe—the Rob Roy model—by cruising the rivers and canals of Europe and the Middle East, and writing several books about his experiences. Macgregor’s counterpart in North America was Nathaniel Holmes Bishop.

A believer in adventure for adventure’s sake, Nathaniel Holmes Bishop (1837-1902) initially gained his fame by hiking through South America when he was only 17 years old. His subsequent book, The Pampas and Andes: A Thousand Miles’ Walk Across South America, published in 1869, became a bestseller. By itself Bishop’s hike would have cemented his place in the Adventurer’s Hall of Fame, but two small-boat journeys a few years later eclipsed that effort.

Influenced by Macgregor’s exploits, Bishop decided in 1874 to cruise the inland waterways of North America from Quebec to the Gulf of Mexico. His boat of choice was an 18' wooden double-paddle canoe, but soon after departing he found the canoe to be too heavy for the many portages required. He gave it up for a canoe molded from heavy-duty paper and glue, a newly developed technique, similar in theory to the fiberglass layup of today.

The book describing his considerable adventures, Voyage of the Paper Canoe (1878), made Nathaniel Holmes Bishop a household name.

Emboldened by fame, he immediately followed that voyage and the book about it with a cruise down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers in a sneakbox, a type of small wooden boat used for duck hunting on Barnegat Bay, New Jersey. His book about the boat and the adventure, Four Months in a Sneak-Box (1879), is now a classic in the small-boat cruising genre.

Albert Strange

The development of the pocket cruiser

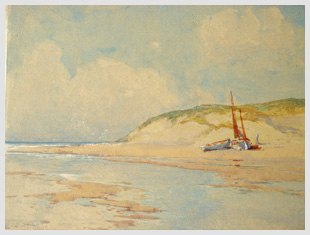

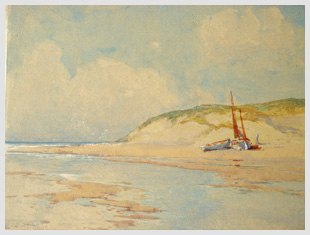

A work by Albert Strange, who specialized

A work by Albert Strange, who specialized

in watercolor sea- and landscapes. The location is unknown.

Courtesy the Albert Strange Association (www.albertstrange.org)In the late nineteenth century, the evolution of the decked canoe branched off in three directions: the paddling-only, the paddling-and-sailing, and the pure-sailing types. English designers and sailors quickly took the lead in the development of the latter craft, starting with the modification of the Rob Roy type with a larger sail rig and ending several decades later with the so-called canoe yawl—a small sailboat suggestive of the pocket cruiser of today whose only resemblance to a canoe was a double-ended hull. There were several English canoe-yawl designers at work during the Victorian era, but of the two foremost —George Holmes and Albert Strange–Albert Strange is the one with a following that carries on to this day.

Strange (1855-1917) was a professional artist, a sailor, a writer, and a yacht designer. The combination of the four, especially the artist part, resulted in canoe-yawl designs that are both seaworthy and beautiful. (I use the present tense, because several of Strange’s original boats still exist today and continue to be sailed, and many more new boats have been and continue to be built to his designs.)

Strange wrote and illustrated several stories about his canoe-yawl cruises that were published in yachting magazines of the day. He also wrote a valuable series on the practical aspects of yacht design that was published from 1914-15 in Britain’s Yachting Monthly magazine. In 1999, that series, with 24 of Strange’s yacht designs and three cruising stories, was reprinted in the book Albert Strange on Yacht Design, Construction and Cruising, by Jamie Clay and Mark Miller.

Here is some of what W.P. Stephens, the dean of American yachting historians, had to say about Albert Strange, whom he knew personally:

“Choosing art as his profession,” Stephens wrote, “[Strange] followed it with the thoroughness that characterized all of his work. He specialized in watercolor, land- and seascapes, but due probably to his modest disposition and his preoccupation with other pursuits he never received the full recognition which his talent merited.... He knew the sea, what it liked and disliked, much of his personal sailing was done in small craft, and all of his yachts were noted for power, stability, and sturdy construction. While the artistic side of his nature was evident in the lines of his yachts, of equal importance was the practical side: the thoroughness of construction shown in all of his specifications.”

Peter Spectre is editor of this magazine.

Thanks to Ole’s invention,

Thanks to Ole’s invention, Bess can get her own ice cream.

(He was a sly one, that Ole.) ©Corbis

Memorial to Nathaniel H. Bishop.

Memorial to Nathaniel H. Bishop.©T.J. Cornu/A.C.A

Influenced by Macgregor’s exploits, Bishop decided in 1874 to cruise the inland waterways of North America from Quebec to the Gulf of Mexico.

A work by Albert Strange, who specialized

A work by Albert Strange, who specialized in watercolor sea- and landscapes. The location is unknown.

Courtesy the Albert Strange Association (www.albertstrange.org)

Strange specialized in watercolor land- and seascapes, but due probably to his modest disposition and his preoccupation with other pursuits he never received the full recognition which his talent merited.

Magazine Issue #

Display Title

From Whence We Came

Secondary Title Text

Issue 115

Sections