“A world without wonder… becomes a world without imagination, and without imagination, man becomes a poor and stunted creature.”

Dear Friends: The will to live is ever so strong this time of year. Last year about this time I went to camp to open up the cabin. A mild winter, unlike this year’s, had left little mark on the woods and the cabin was in pretty good order except for a smelly mouse nest in the blanket chest, and another in my apple box fiddle. Again! Our camp is on Cobscook Bay in Washington County, off a clamming road that is off a town road. You can’t drive up to camp, so everything has to be carried in and out. It has no electricity, phone, or running water. The result of all this is an enveloping quiet that floats softly down around you, washing away the noise and clatter of the human realm and bathing you in the calm of the woods and shore, an increasingly rare and deeply healing experience. The ravens were the first greeters, with a chorus of croaks and gurgles followed by the sharp call of a pileated woodpecker from the spire of the big spruce that lost its top in the ice storm of 1998. Everywhere the trees and fields were lush with new growth. Yellow hawkweed, daisies, and buttercups waved in the breeze as bumblebees and digger bees hopped from bloom to bloom, smeared in living pollen. The soft, new growth on balsam firs wiggled in the wind. Across the brook a mourning dove stood on the edge of its nest calmly feeding its squabs with crop milk while their heads stretched up in the cool shade high in a white birch. Robins and bluejays played tag in the clearing, while hermit thrushes and white-throated sparrows called from the woods, and loons and eiders called from the water. Chipmunks scurried through fallen leaves, and a meadow mouse skittered across the cabin floor. The daily will to live was everywhere expressed in leaf, fur, and feather, call and song. On the last morning, as I left by the old clamming road, a young buck, sleek and fattened on fresh, new browse with its new antlers covered in velvet, stared at me with head high, then loped off over some blow-downs in no hurry at all. Illustration by Candace Hutchinson

Seedpod to carry around with you

From Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself”: “…And a mouse is miracle enough to stagger sextillions of infidels.”

Natural events, early June

Our spirits are lightened with the lupine and daisies blooming along the roadsides, and the daylilies, irises, and poppies in our gardens. We greet each other warmly around town; there is a spring in our step. Each one’s joy amplifies everyone’s as memories of the cold fade away in a blaze of golden glory.

The spring young of many creatures are starting to show themselves hereabouts. We watched a pair of small, month-old chipmunks frolicking in the front yard, and running up and down the old pear tree outside the kitchen window. They darted in and out of this new and wild world, exploring the holes in the old tree and the burrows in the ground that, unbeknownst to them, were the homes of generations of their ancestors. They seem so thin and innocent. Their coats are fresh and brightly colored, though their fur is hardly even grown out yet, like the fuzz on a baby’s head.

I watch a young finch fledgling at the feeder. It is not so easily disturbed by our presence as its parents would surely have been. I stand quietly within an arm’s reach of the tiny, young bird as it breaks open its first few sunflower seeds, almost close enough to smell its breath. I see four young woodcocks bopping across the Cedar Swamp Road.

These young seem so fearless, not running or flying quickly from our presence, perhaps because they do not yet know the dangers of this world. It makes them so precious that I can hardly express it. Bell your cat.

Field and forest report, early June

Bouncing Bet, buttercups, and white and gold daisies are in bloom, with their beautiful, sun-loving faces so open and cheerful. Very hardy, they are. The wind and rain beat them down for a time, but they rise again. Meanwhile, the lovely lupines take an awful beating. They grow large and lush through the warm spring, but June rains break them down far and wide. Yet, even lying flat on the ground, they turn their blossoms upward; they still give off their fresh, peppery aroma; they will never be stopped or stayed from producing their seeds for the future.

Illustration by Candace Hutchinson

Seedpod to carry around with you

From Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself”: “…And a mouse is miracle enough to stagger sextillions of infidels.”

Natural events, early June

Our spirits are lightened with the lupine and daisies blooming along the roadsides, and the daylilies, irises, and poppies in our gardens. We greet each other warmly around town; there is a spring in our step. Each one’s joy amplifies everyone’s as memories of the cold fade away in a blaze of golden glory.

The spring young of many creatures are starting to show themselves hereabouts. We watched a pair of small, month-old chipmunks frolicking in the front yard, and running up and down the old pear tree outside the kitchen window. They darted in and out of this new and wild world, exploring the holes in the old tree and the burrows in the ground that, unbeknownst to them, were the homes of generations of their ancestors. They seem so thin and innocent. Their coats are fresh and brightly colored, though their fur is hardly even grown out yet, like the fuzz on a baby’s head.

I watch a young finch fledgling at the feeder. It is not so easily disturbed by our presence as its parents would surely have been. I stand quietly within an arm’s reach of the tiny, young bird as it breaks open its first few sunflower seeds, almost close enough to smell its breath. I see four young woodcocks bopping across the Cedar Swamp Road.

These young seem so fearless, not running or flying quickly from our presence, perhaps because they do not yet know the dangers of this world. It makes them so precious that I can hardly express it. Bell your cat.

Field and forest report, early June

Bouncing Bet, buttercups, and white and gold daisies are in bloom, with their beautiful, sun-loving faces so open and cheerful. Very hardy, they are. The wind and rain beat them down for a time, but they rise again. Meanwhile, the lovely lupines take an awful beating. They grow large and lush through the warm spring, but June rains break them down far and wide. Yet, even lying flat on the ground, they turn their blossoms upward; they still give off their fresh, peppery aroma; they will never be stopped or stayed from producing their seeds for the future.

Illustration by Candace HutchinsonAnother seedpod to carry around with you

From Malvina Reynolds: “God bless the grass that’s gentle and low. Its roots they are deep and its will is to grow. And God bless the truth, the friend of the poor; And the wild grass growing at the poor man’s door; And God bless the grass.”

Natural events, July

In summer it’s easy for us to forget that the crawling traffic everywhere, the bright plastic kayaks, the pop-up tents, the flip-flops, the funny T-shirts, the fried clams are all about getting back to Nature. This is good. If you can get past the awkwardness, it’s heart-warming, really, this hunger and thirst for the wild, drawing the multitudes from their hectic hives in sweltering cities to perch on a dirty picnic bench by the water and enthusiastically enjoy a steaming fresh lobster, or to struggle up a rugged mountain and see the soothing view from the summit. It’s enough to restore a little hope in humanity, seeing the swooning tourists thirstily soaking up the beauties of this fragile planet. Their hunger is so great, as is their love.

We spend a week at our camp taking council with cormorants and laughing with loons, and fantasizing in the fog. We watch the bats and the fireflies, and even have a sweet birch fire in the woodstove on a day while the rest of the Northeast is sweating. We come back revived. Our elected leaders elect to leave their work behind and take a summer recess—probably good news for the rest of us. The thirst for the wild reaches all the way to the top of our human pyramid, though maybe not all the way to the bottom.

Summer odds & ends

Illustration by Candace HutchinsonAnother seedpod to carry around with you

From Malvina Reynolds: “God bless the grass that’s gentle and low. Its roots they are deep and its will is to grow. And God bless the truth, the friend of the poor; And the wild grass growing at the poor man’s door; And God bless the grass.”

Natural events, July

In summer it’s easy for us to forget that the crawling traffic everywhere, the bright plastic kayaks, the pop-up tents, the flip-flops, the funny T-shirts, the fried clams are all about getting back to Nature. This is good. If you can get past the awkwardness, it’s heart-warming, really, this hunger and thirst for the wild, drawing the multitudes from their hectic hives in sweltering cities to perch on a dirty picnic bench by the water and enthusiastically enjoy a steaming fresh lobster, or to struggle up a rugged mountain and see the soothing view from the summit. It’s enough to restore a little hope in humanity, seeing the swooning tourists thirstily soaking up the beauties of this fragile planet. Their hunger is so great, as is their love.

We spend a week at our camp taking council with cormorants and laughing with loons, and fantasizing in the fog. We watch the bats and the fireflies, and even have a sweet birch fire in the woodstove on a day while the rest of the Northeast is sweating. We come back revived. Our elected leaders elect to leave their work behind and take a summer recess—probably good news for the rest of us. The thirst for the wild reaches all the way to the top of our human pyramid, though maybe not all the way to the bottom.

Summer odds & ends Illustration by Candace Hutchinson

We’ve been puzzling for years over Japanese knotweed, often called “bamboo” locally. It was originally imported as an ornamental, but is viewed as a pest because it spreads rapidly and is confoundingly hard to eradicate once it takes hold. On Monhegan Island, they spread old rugs over it to smother it, with some success. I just mow over it whenever it appears in my yard in Eastport. In parts of Canada they spray it with saltwater to some effect.

But knotweed has some good qualities, too. Its shoots can be eaten like rhubarb. Its flowers make great honey. It produces a tremendous amount of fiber every year, sending up thick stalks six feet high with broad leaves. You’d think there might be some practical use for this. Making paper maybe? Animal feed? If you have a use for knotweed, or a non-toxic method for its control, please let me know and I’ll publish your suggestions.

I want to respectfully acknowledge the action last year of Acadian Seaplants of Pembroke in honoring the no-harvest registry of Cobscook Bay landowners who do not want rockweed taken from their shores until the sustainability of this harvest is determined. Acadian’s action is not only good business, it is also good resource management, not to mention good neighborliness. Maybe they would consider expanding into the knotweed market?

Congratulations to the Penobscot East Resource Center on the opening of their new headquarters in Stonington last summer. They are partnering with the Cobscook Bay Resource Center and others up and down the coast in advocating for Maine fisheries. Heaven knows, the fisheries need all the advocates they can get.

Most of us are accustomed to visitors at this season. Some are pleasant and some not, reminding of us of Poor Richard’s remark about fish and visitors. Old friends aside, along with the danged earwigs you may be seeing a small roach scurrying about the house these days. Don’t panic. This is likely the harmless wood roach, a seasonal visitor that will depart of its on accord soon enough, though maybe not in three days. If you must, you can sprinkle a little borax in the corners.

More pleasant seasonal visitors are the chimney swifts. They can be recognized by their twittering, circling flight and their crescent-shaped wings as they sickle through the sky to dive recklessly down the chimney. They nest in stone and brick chimneys, where they raise their young. Swifts are worth their weight in bug-catching, snatching thousands of mosquitoes and flies from the evening skies every night. You might remember this before you start a fire in the stove or fireplace on a cool night.

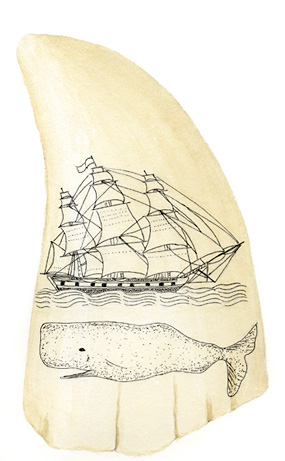

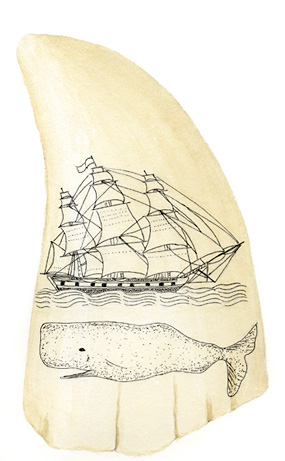

Lastly, we offer a tribute to some of our most beloved summer visitors, the seals and the whales. It is remarkable how recently we attacked these marvelous mammals on sight and hunted them to scarcity in the North Atlantic, while now we venture out on the waters, not to kill them, but to simply watch them and delight in the sight as they frolic with the joyous freedom of the deep. Hope for the whales equals hope for the humans.

Two final seedpods to carry around with you

From Robert Cushman Murphy, American naturalist: “No being can reveal more marvelous grace than a whale.”

And from Psalm 104: “O Lord, how manifold are your works; in wisdom you have made them all. Yonder is the sea, great and wide, filled with numberless things… there go the ships and the whales which you have formed to sport in it.”

That’s the almanack for this time. But don’t take it from us—we’re no experts. Go out and see for yourself.

Illustration by Candace Hutchinson

We’ve been puzzling for years over Japanese knotweed, often called “bamboo” locally. It was originally imported as an ornamental, but is viewed as a pest because it spreads rapidly and is confoundingly hard to eradicate once it takes hold. On Monhegan Island, they spread old rugs over it to smother it, with some success. I just mow over it whenever it appears in my yard in Eastport. In parts of Canada they spray it with saltwater to some effect.

But knotweed has some good qualities, too. Its shoots can be eaten like rhubarb. Its flowers make great honey. It produces a tremendous amount of fiber every year, sending up thick stalks six feet high with broad leaves. You’d think there might be some practical use for this. Making paper maybe? Animal feed? If you have a use for knotweed, or a non-toxic method for its control, please let me know and I’ll publish your suggestions.

I want to respectfully acknowledge the action last year of Acadian Seaplants of Pembroke in honoring the no-harvest registry of Cobscook Bay landowners who do not want rockweed taken from their shores until the sustainability of this harvest is determined. Acadian’s action is not only good business, it is also good resource management, not to mention good neighborliness. Maybe they would consider expanding into the knotweed market?

Congratulations to the Penobscot East Resource Center on the opening of their new headquarters in Stonington last summer. They are partnering with the Cobscook Bay Resource Center and others up and down the coast in advocating for Maine fisheries. Heaven knows, the fisheries need all the advocates they can get.

Most of us are accustomed to visitors at this season. Some are pleasant and some not, reminding of us of Poor Richard’s remark about fish and visitors. Old friends aside, along with the danged earwigs you may be seeing a small roach scurrying about the house these days. Don’t panic. This is likely the harmless wood roach, a seasonal visitor that will depart of its on accord soon enough, though maybe not in three days. If you must, you can sprinkle a little borax in the corners.

More pleasant seasonal visitors are the chimney swifts. They can be recognized by their twittering, circling flight and their crescent-shaped wings as they sickle through the sky to dive recklessly down the chimney. They nest in stone and brick chimneys, where they raise their young. Swifts are worth their weight in bug-catching, snatching thousands of mosquitoes and flies from the evening skies every night. You might remember this before you start a fire in the stove or fireplace on a cool night.

Lastly, we offer a tribute to some of our most beloved summer visitors, the seals and the whales. It is remarkable how recently we attacked these marvelous mammals on sight and hunted them to scarcity in the North Atlantic, while now we venture out on the waters, not to kill them, but to simply watch them and delight in the sight as they frolic with the joyous freedom of the deep. Hope for the whales equals hope for the humans.

Two final seedpods to carry around with you

From Robert Cushman Murphy, American naturalist: “No being can reveal more marvelous grace than a whale.”

And from Psalm 104: “O Lord, how manifold are your works; in wisdom you have made them all. Yonder is the sea, great and wide, filled with numberless things… there go the ships and the whales which you have formed to sport in it.”

That’s the almanack for this time. But don’t take it from us—we’re no experts. Go out and see for yourself.

Rob McCall is a journalist, naturalist, fiddler, and for the past 22 years, has been pastor of The First Congregational Church of Blue Hill, Maine, UCC. Readers can contact him directly via e-mail: awanadjoalmanack@gmail.com or post a comment using the form below.

—Henry Beston

Dear Friends: The will to live is ever so strong this time of year. Last year about this time I went to camp to open up the cabin. A mild winter, unlike this year’s, had left little mark on the woods and the cabin was in pretty good order except for a smelly mouse nest in the blanket chest, and another in my apple box fiddle. Again! Our camp is on Cobscook Bay in Washington County, off a clamming road that is off a town road. You can’t drive up to camp, so everything has to be carried in and out. It has no electricity, phone, or running water. The result of all this is an enveloping quiet that floats softly down around you, washing away the noise and clatter of the human realm and bathing you in the calm of the woods and shore, an increasingly rare and deeply healing experience. The ravens were the first greeters, with a chorus of croaks and gurgles followed by the sharp call of a pileated woodpecker from the spire of the big spruce that lost its top in the ice storm of 1998. Everywhere the trees and fields were lush with new growth. Yellow hawkweed, daisies, and buttercups waved in the breeze as bumblebees and digger bees hopped from bloom to bloom, smeared in living pollen. The soft, new growth on balsam firs wiggled in the wind. Across the brook a mourning dove stood on the edge of its nest calmly feeding its squabs with crop milk while their heads stretched up in the cool shade high in a white birch. Robins and bluejays played tag in the clearing, while hermit thrushes and white-throated sparrows called from the woods, and loons and eiders called from the water. Chipmunks scurried through fallen leaves, and a meadow mouse skittered across the cabin floor. The daily will to live was everywhere expressed in leaf, fur, and feather, call and song. On the last morning, as I left by the old clamming road, a young buck, sleek and fattened on fresh, new browse with its new antlers covered in velvet, stared at me with head high, then loped off over some blow-downs in no hurry at all.

Illustration by Candace Hutchinson

Illustration by Candace HutchinsonConsider the many benefits of letting grassy fields grow unmown. There are the wildflowers waving in the breeze, and the sound of crickets, and the wonder of the grass’s vast variety growing to full seed-bearing maturity.

Mountain report, early June

Often at this tine of year Awanadjo is true to her Algonkian name—in English, “Small, Misty Mountain”—with a wreath of clouds over her head covering and then uncovering the summit through the damp days and dark nights. The hermit thrush plays her beautiful flute in the Wisdom Woods as the fog drips from the trees, and the mosses and lichens grow lush in the liquid.

Field and forest report

Consider the many benefits of letting grassy fields grow unmown. There are the wildflowers waving in the breeze, and the sound of crickets, and the wonder of the grass’s vast variety growing to full seed-bearing maturity. Grasses mown down again and again to a regular three inches look the same from spring to fall: sterile, interrupted, never reaching their fullness. But let go, they show their marvelously particular features. Further, long grass holds moisture in the soil during drought, and its woven, matted turf secures the soil and halts erosion.

And then, of course, there is the hay. In former days, hay was a foundation crop for New England farmsteads, feeding livestock through the winter months. Old pictures of our village show wide-open fields within the town boundaries and away up the mountain slopes. These meadows were for hay and pasture. Nowadays, acres upon acres of rich fields full of protein are bush-hogged down each year because we have little use for hay. But we have not forgotten the monumental labor that went into clearing and keeping those old fields, so we mow them out of rote memory.

A few farmers still make hay in our area, but it is barely a break-even operation, done more for love than for money. Perhaps that will change as the present economic crisis becomes the new normal.

I can recognize a few grasses: orchard grass, foxtail, timothy, and fescue, but these are just a few of hundreds of others out there. You’d think it would be easy enough to find a guide to Maine wild grasses somewhere in the vast on-line universe, but every time I search I am guided back to weeds—weeds or wordy descriptions with no pictures. The common knowledge of 100 years ago is disappearing before our eyes.

The last and greatest benefit of grass is its humble healing diligence, binding up the wounds we inflict upon the earth and upon each other. By the patient efforts of grass, battlefields are changed from red and brown to green. Scorched earth is turned from burnt and black to verdant. Slipping into places we have laid waste and turning them green again, grasses are not to be disdained as weeds. As they quietly and humbly show us how to re-green and redeem the planet, the grasses are to be honored as healers of the wounded earth, and the silent, swaying ambassadors of life sent to reclaim the dominions of death.

Illustration by Candace Hutchinson

Illustration by Candace Hutchinson Illustration by Candace Hutchinson

Illustration by Candace HutchinsonYr. mst. hmble & obd’nt servant,

Rob McCall

Rob McCall is a journalist, naturalist, fiddler, and for the past 22 years, has been pastor of The First Congregational Church of Blue Hill, Maine, UCC. Readers can contact him directly via e-mail: awanadjoalmanack@gmail.com or post a comment using the form below.

Magazine Issue #

Display Title

Awanadjo Almanack

Secondary Title Text

Blue Hill: the Town, the Bay, the Mountain

Sections