Thomas Fleming Day, Lady Anna Brassey, Edwin Tappan Adney: Author-adventurers all.

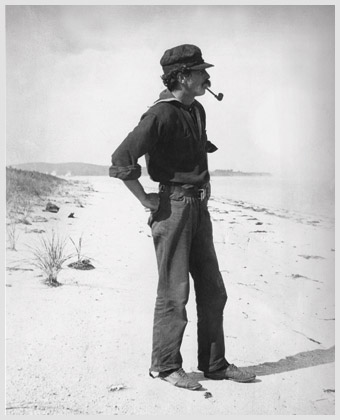

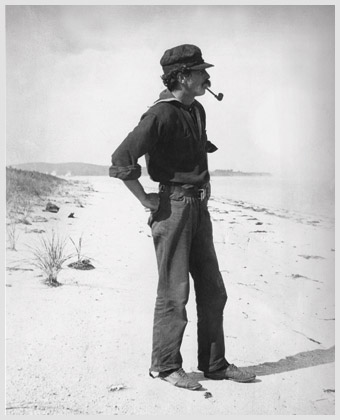

Thomas Fleming Day: A man of the sea on the shore.

Thomas Fleming Day: A man of the sea on the shore.

©Mystic Seaport, photography collection,

Mystic, Connecticut, #1996.96.669.Thomas Fleming Day

Editor, Writer, Sailor

If you are of a certain age, you must remember The Rudder, the boating magazine—the first of its kind—that set the standard for all others. What made it so special? Its first editor was Thomas Fleming Day, an enthusiast with a deep knowledge of the subject and a well-founded point of view.

The Rudder was Thomas Fleming Day, and Thomas Fleming Day was The Rudder. He treated his readers as intelligent human beings. He didn’t pander to his advertisers. He recognized yacht design as an evolution, with a connected past, present, and future. He was a sailor. Above all, he was a literate, literary man of strong opinion, the author of articles, editorials, poetry, and books.

Born in Somersetshire, England, Thomas Fleming Day (1861-1927) came to the United States when he was seven years old and grew up with boats on the Long Island Sound waterfront. “A noble art makes noble men,” he once wrote, “and there is no nobler art than seamanship.” He learned that art well.

Day began his working life as a manufacturer’s rep, selling marine hardware, canoes, and other small craft. In 1891, recognizing a need for a magazine that was as much about boating as it was of yachting, he founded The Rudder. He soon became the most dominant voice in the field—outspoken, argumentative, persuasive, controversial—known to his supporters as Uncle Tom, The Old Man, Skipper Day, Captain Day; to his detractors as The Crank.

One of Day’s then-controversial notions was that too many boats spent too much time either at their moorings or sailing alongshore; he felt that amateur sailors in boats, not necessarily yachts, should sail offshore. In 1904, to promote his ideas, he organized a 330-mile offshore race from Sandy Hook around the Nantucket Shoals Lightship to Marblehead. In 1905 he organized another offshore race from Brooklyn, New York, to Hampton Roads, Virginia. And then in 1906 he organized the granddaddy of them all, the Bermuda Race, the event that gained him the nickname Offshore Tommy.

In 1911, to demonstrate that amateurs could easily take small cruising boats across the Atlantic Ocean, Day and a crew of two sailed from Newport, Rhode Island, to Gibraltar in the 32-foot yawl Sea Bird, designed by Charles Mower and himself. Day’s book about the passage, Across the Atlantic in Sea Bird, became a best-seller. The next year, to demonstrate the reliability of the internal combustion engine for marine use, he and a crew of three took the 35-foot motorboat Detroit from New York to St. Petersburg, Russia. His account of that passage, Voyage of Detroit, was another best-seller.

Day’s other books included Hints to Young Skippers, an excellent treatise on boat husbandry and seamanship, and Songs of Sea and Sail, a book of poetry.

Thomas Fleming Day retired from The Rudder in 1917 and opened a yacht chandlery in New York City. A sign on the wall there proclaimed to customers, “Give Up All Hope Ye Who Enter Here.”

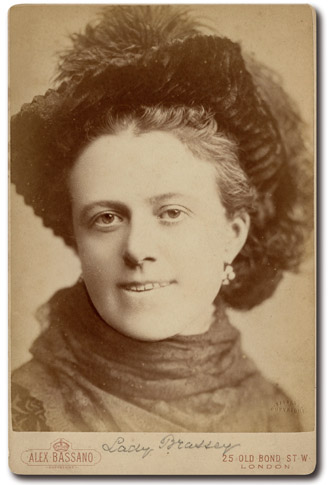

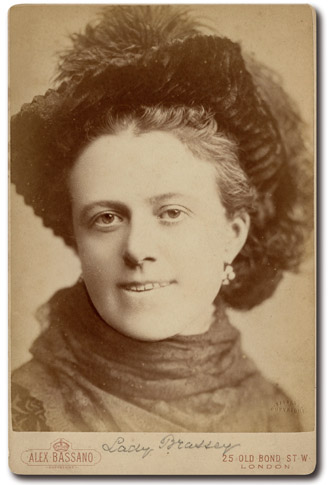

Lady Anna Brassey: She sailed the seas, she was buried at sea.

Lady Anna Brassey: She sailed the seas, she was buried at sea.

©National Portrait Gallery, London.Lady Anna Brassey

Sailor, Writer

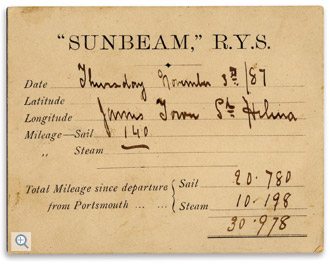

Another offshore sailor with a literary bent, Lady Anna Brassey (née Allnutt) (1839-1887), wife of Lord Thomas Brassey, spent a good amount of her adult life sailing the oceans of the world. Her means of carriage, however, wasn’t anything as plebian as a 32-foot yawl or a 35-foot motorboat. Hers (and her husband’s) was the 157-foot three-masted topsail-yard schooner Sunbeam. Designed by St. Clare Byrne especially for a circumnavigation, it had a 271⁄2-foot beam and was powered (when it wasn’t sailing) by a coal-fired steam engine that could produce a cruising speed of 8 knots and a top speed of 10.

The Sunbeam, on its major voyage around the world in 1876-77, carried a complement of 43, among them:

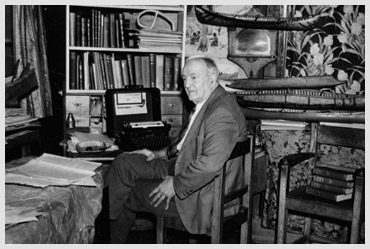

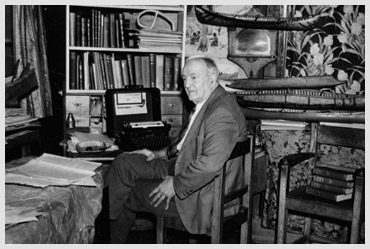

Edwin Tappan Adney: at work in his study in 1944.

Edwin Tappan Adney: at work in his study in 1944.

The Mariners’ Museum, Newport News, VirginiaEdwin Tappan Adney

Correspondent, Ethnologist, Preserver of the Bark Canoe

While Thomas Fleming Day and Lady Anna Brassey were about salt water, Edwin Tappan Adney (1868-1950) was all about fresh. Born in Athens, Ohio, where his father was a university professor, his interests as a young man revolved around the outdoors, photography, fine art, and journalism.

In the mid-1880s, on a visit to his wife’s hometown of Woodstock, New Brunswick, Canada, Adney met a Malecite Indian who built bark canoes. He became fascinated by the subject and began making drawings of bark canoes and building scale models. His first published work on the subject appeared in a supplement to Harper’s Weekly for young people.

Adney signed on as a correspondent for Harper’s, and in 1897 his interests in photography, art, and the outdoors paid off. He was sent to the Klondike region of the Yukon and became one of the earliest professional journalists to report on the spectacular gold rush that was just getting under way there. His dispatches, written under the same conditions of privation endured by the miners, were a sensation when published in the United States. So, too, was the book he wrote about his adventures, The Klondike Stampede, published in 1900. Many of the photographs he took were published in papers and magazines around the world; in fact, several of his photographs of packers climbing the Chilcoot and White Passes, and drivers taking boats down the Yukon River rapids are archetypes of the Klondike gold rush.

Now a Canadian citizen, Adney fought in World War I and then moved to Montreal, where he began a career as a commercial artist specializing in heraldry and worked as a consultant on Indian lore at McGill University. In his spare time he continued his research into the indigenous boats, canoes, and kayaks of North America and the cultures that produced them, and went on building models and making sketches and drawing plans. His work is now considered central to the saving of the art of birchbark canoe building.

Originally, Adney’s collection of more than 100 bark canoe models went to the Strathcona Ethnological Museum at McGill University. They were acquired in 1940 by the Mariner’s Museum, Newport News, Virginia, where they are now preserved.

The book Adney had begun to write based on his research and never finished was finally published in 1964 by the Smithsonian Institution. Co-authored by Howard I. Chapelle, who worked with Adney’s notes and partial manuscript, The Bark Canoes and Skin Boats of North America is the benchmark on which nearly all further research on the subject is based.

Peter Spectre is editor of this magazine and is himself a small-boat enthusiast and story-teller.

Thomas Fleming Day: A man of the sea on the shore.

Thomas Fleming Day: A man of the sea on the shore.©Mystic Seaport, photography collection,

Mystic, Connecticut, #1996.96.669.

Lady Anna Brassey: She sailed the seas, she was buried at sea.

Lady Anna Brassey: She sailed the seas, she was buried at sea. ©National Portrait Gallery, London.

Lord Thomas Brassey

Lady Anna Brassey

Four little Brasseys

One maid for the Lady

One nannie for the children

One stewardess

Four stewards

Three cooks

Four guests

Two dogs

Three birds

One kitten

and a full complement of paid officers and sailors

Lady Brassey wrote a hugely popular book about the voyage. The Voyage in the Sunbeam, Our Home on the Ocean for Eleven Months (1878) was published in several editions in England and the United States, and was translated into many other languages. As much about what the author saw when she arrived as how she got there, it was one of the most popular travel books of the Victorian era.

The Voyage in the Sunbeam wasn’t Lady Brassey’s first book, nor was it her last. In the early years of their marriage, in 1869, the Brasseys cruised in a smaller yacht through the Mediterranean to the Near East. Later she collected the long letters she wrote to her father about the adventure and published them privately in The Flight of the Meteor. In 1872 the couple sailed in another yacht across the Atlantic to Canada and the United States; the story of that cruise was also privately published in A Cruise in the Eothen.

After the Sunbeam’s voyage around the world, the Brasseys spent several years sailing to romantic venues. Lady Brassey continued to write best-selling books about their experiences. Sunshine and Storm in the East; or, Cruises to Cyprus and Constantinople was published in 1880; In the Trades, the Tropics, and the Roaring Forties in 1885. Her last book, The Last Voyage of the Sunbeam, published posthumously in 1889, was about their cruise to the Antipodes.

Lady Anna Brassey, the most successful writer of cruising accounts of her age, died aboard the Sunbeam in mid-ocean on the way from Australia to Mauritius. She was buried at sea, September 14, 1887.

“Fear in storm and tempest she never knew,” her husband, the heartbroken Lord Brassey, wrote in his introduction to her last book. “She made yachting, notwithstanding its drawbacks, a source of pleasure.”

Edwin Tappan Adney: at work in his study in 1944.

Edwin Tappan Adney: at work in his study in 1944.The Mariners’ Museum, Newport News, Virginia

Magazine Issue #

Display Title

From Whence We Came

Secondary Title Text

Issue 109 - April/May 2010

Sections

Click on image to expand.

Click on image to expand.