From Hornblower to the Sea Scouts: Forester, Kent, and Lane

C.S. Forester

The man who imagined Hornblower

Before there was Patrick O’Brian, before there was Alexander Kent, before there were Dudley Pope and Richard Woodman and all the rest of the modern-day fictionalizers of the Great Age of Fighting Sail, there was C.S. Forester, and with his series about the exploits of Horatio Hornblower, Royal Navy, he set the standard.

C.S. (Cecil Scott) Forester was the pen name of Cecil Louis Troughton Smith (1899-1966), born in Cairo, Egypt, of English parents. When he was three years old Forester moved with his mother to England, where he was educated. His first novel, A Pawn Among Kings, published when he was in his 20s, was set in the Napoleonic era, but had a non-naval theme. After following up with a series of very successful novels, Forester went to Hollywood to work temporarily as a screenwriter; on his way home by sea he began work on The Happy Return, the first of his Horatio Hornblower series, which would make him famous.

At the outset of World War II, Forester returned to Hollywood to write scripts and other works in support of the war effort, remaining in California for the rest of his life. During his career he wrote 35 novels, five biographies, three children’s books, two plays, and several nonfiction works, including an autobiography. His most notable nautical fiction includes The Ship, The African Queen (made into the famous Bogart/ Hepburn film), The Captain from Connecticut, and, of course, the Hornblower series. His nonfiction includes two first-class cruising stories about his small-boat adventures—The Voyage of the Annie Marble and The Annie Marble in Germany —and the excellent Age of Fighting Sail.

“A successful book is not made of what is in it,” Mark Twain once wrote, “but what is left out of it.” C.S. Forester’s work best exemplifies that principle. He knew that unloading onto the page everything an author knows about a subject (or a character) does not necessarily illuminate it. His prose is clean, elegant, and unpretentious; his plots are complex enough to be gripping yet simple enough to be followed; his characters are believable in the sense that they have the clarity of moral vision balanced by the weakness of normal people; and his descriptions are understandable even if you are unfamiliar with seamanship in the age of the square rigger and comprehensible even without a nautical glossary or dictionary at your side.

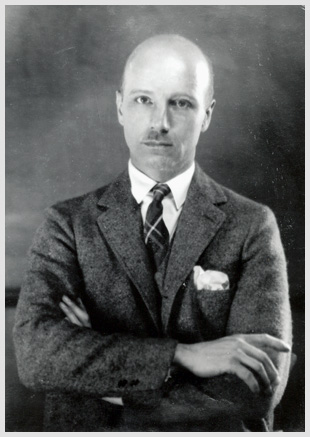

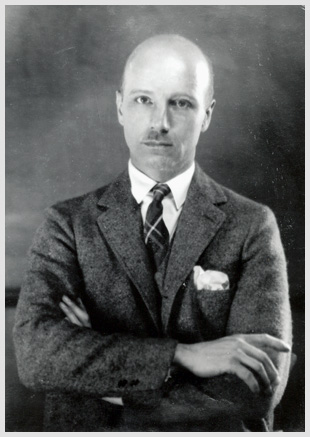

Rockwell Kent

Rockwell Kent

Photo: Plattsburgh State Art Museum

Rockwell Kent Collection

Bequest of Sally Kent BortonRockwell Kent

The sailor as artist, the artist as sailor

Few artists have made their mark as sailors; fewer still have written books that combine their sailing and their art. Rockwell Kent (1882-1971) did both.

Born in Tarrytown, New York, owner of a farm in the Adirondacks, a fixture for many years on Monhegan Island, Kent was a leftward-leaning artist with a penchant for adventure in high latitudes (Alaska, Newfoundland, Greenland, Tierra del Fuego, etc.) in the era between the world wars. He became well-known by illustrating books and gained his fame creating fine art in a style that was at once straightforward and transcendental.

Kent illustrated several books with nautical themes, including a three-volume limited edition of Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick, later released in a one-volume version for a larger market, and A Treasury of Sea Stories, edited by Gordon C. Aymar. Of the several books he both wrote and illustrated, two— N by E, and Voyaging —are about his sailing experiences. The former describes a passage from New York to Greenland via Newfoundland in a Colin Archer double-ender that ended in shipwreck; the latter is about Kent’s experiences in a converted lifeboat along the Strait of Magellan and around Tierra del Fuego. On the surface both are genre pieces, but deep down inside they are Literature illustrated with Art.

Here, from N by E, is Rockwell Kent on the loneliness of the long-distance passage maker:

“Twilight, the ocean, eight o-clock have come; I take the helm on my watch. The wind has risen, the horizon is dark against a livid sky. It’s cold. Never again for months to come do my thoughts run to nakedness. Nor do I see green fields, nor thriving homesteads, nor people long enough except to part from them; nor—though it’s June—the summer; not for a thousand miles. And as it darkens and the stars come out, and the black sea appears unbroken everywhere save for the restless turbulence of its own plain, as the lights are extinguished in the cabin—then I am suddenly alone. And almost terror grips me for I now feel the solitude; under the keel and overhead the depths,—and me, enveloped in immensity. How strange to be here in a little boat!—and not by accident....”

For an understanding of Kent’s life—and his politics—see his two autobiographical works, It’s Me O Lord and This Is My Own. For an appreciation of his art, see Rockwell Kent: An Anthology of His Work, edited by Fridolph Johnson.

Carl D. Lane

The master of practical prose

If you were in the Boy Scouts in the years after World War II and had graduated to the Explorer Scouts or the Sea Scouts, you knew Carl Lane’s words. You may not have known that he wrote them, but you knew them. Lane was the author of the Explorer Scout Manual and the Sea Scout Manual, as well as the Handbook for Crew Leaders and the Seamanship handbook for the merit badge program. But that was not all. He also wrote a vast number of other nonfiction books and magazine articles, as well as a fair amount of fiction.

And that was not the end of it, either. In the early 1950s he founded and ran, with his son Bob, Rockport’s Penobscot Boat Works, a shop famous for its series of lapstrake runabouts and a long line of trawler-yachts and seagoing houseboats—the Penbos—that were, to steal a phrase from an old colleague, so salty they made your eyes rust.

Carl D. [Daniel] Lane (1899-1995) was born in New York City, lived on the Connecticut coast, and eventually moved to Maine. His boats and his writings were inspired by personal experience: the Penbos by his long experience with motorcruisers and his many passages along the coast and the inland waterway between New England and Florida; his writing by a monomaniacal love of boats and boating. His work was published in many of the boating magazines of the day; his short fiction was published by, among others, the Saturday Evening Post and Collier’s. His practical books, many of which were best sellers and remained in print for years, include The Boatman’s Manual, The Cruiser’s Manual, Boatowner’s Sheet Anchor, Navigation the Easy Way, and others.

Lane’s writing is clear, direct, opinionated, accurate, and captivating. (An example: “No boat need strand on a strange coast if the skipper is a navigator and seaman in fact, not theory. No boat need suffer a ‘licking’ at sea if the skipper is a seaman and sailor in fact, not theory. No boat need suffer any form of shipwreck if her skipper has fitted her out and equipped her for the purposes of her use, wisely and generously.”)

His illustrations—simple pen-and-ink sketches—are as clean, simple, and concise as his writing.

Lane’s style is boaty, not yachty. He belonged to a school of nautical writers of the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s that included Hervey Garrett Smith, William Atkin, Clifford Ashley, and Wade Ham DeFontaine. No Herreshoffian posturing here. None of the class distinctions inherent in yachting of that time. Just unadulterated boatiness, with emphasis on the happy, almost childlike appreciation of the traditions of the sea.

Peter Spectre is editor of this magazine and is himself a small-boat enthusiast and story-teller.

Rockwell Kent

Rockwell KentPhoto: Plattsburgh State Art Museum

Rockwell Kent Collection

Bequest of Sally Kent Borton

Magazine Issue #

Display Title

From Whence We Came

Secondary Title Text

Issue 106

Sections