Photographs by Donnie Mullen

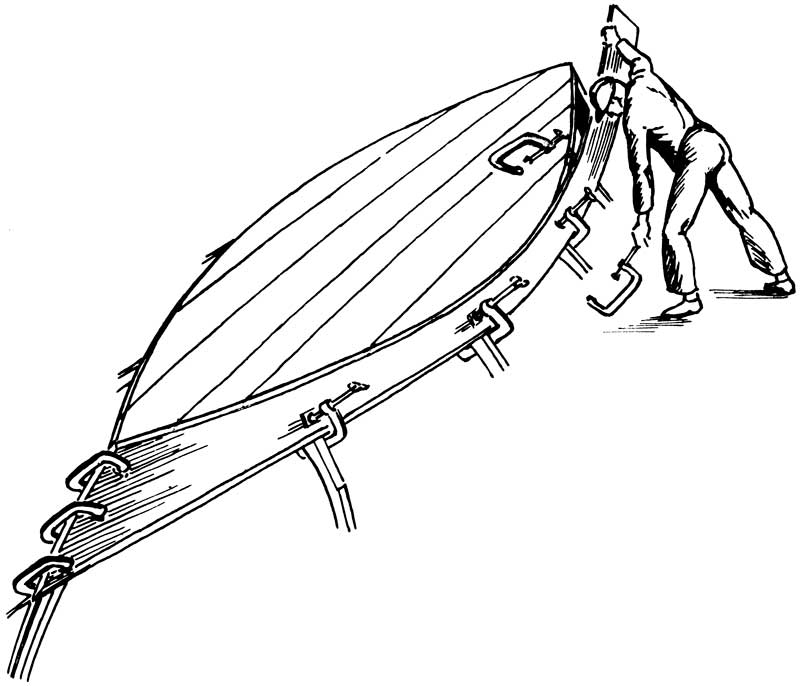

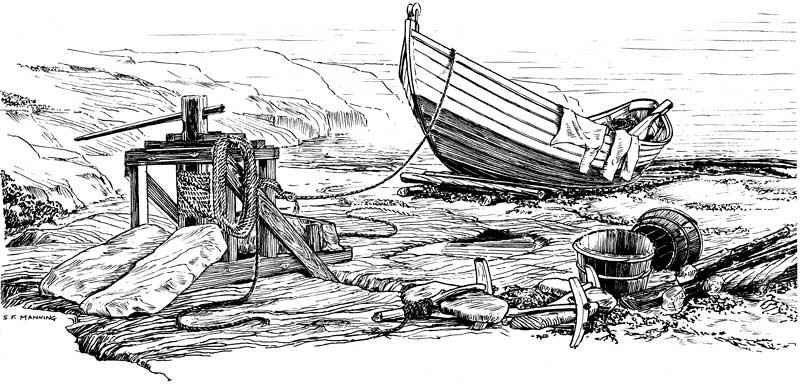

Illustration top left by Sam Manning

Illustration top left by Sam Manning

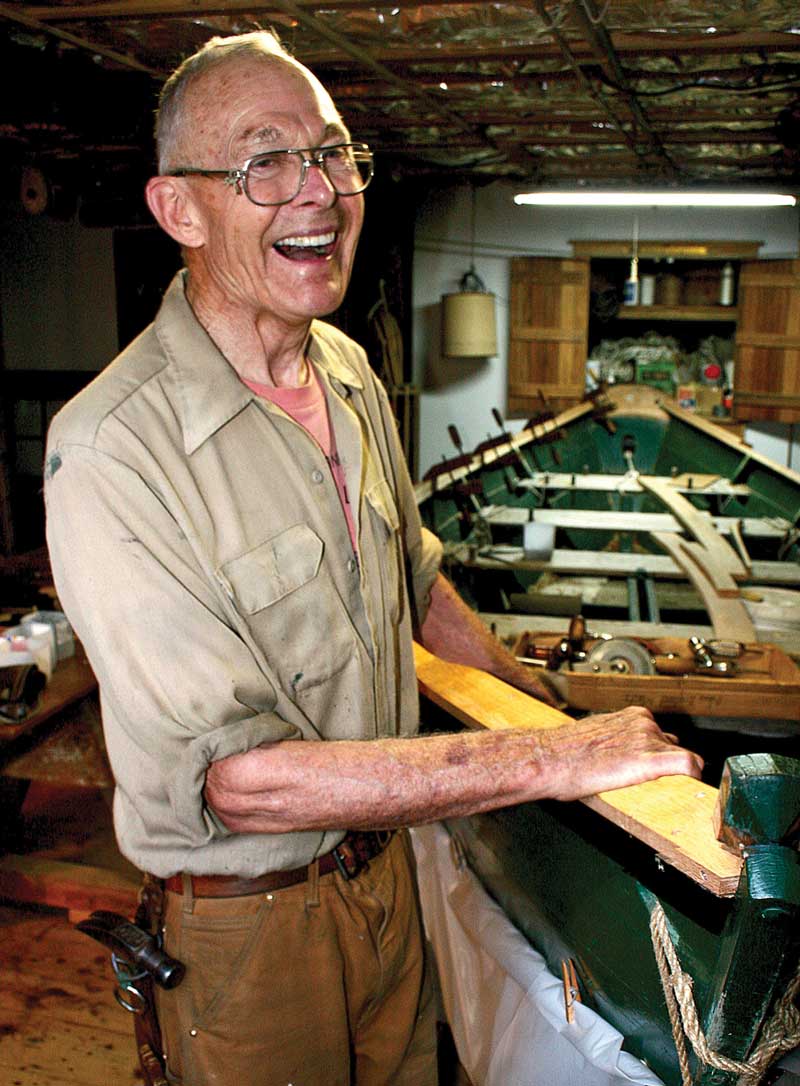

On a cold January afternoon, dormant floats crowd the Camden Town Landing as Sam Manning prepares for his daily row. Crusty snow covers the benches; schooners rest wrapped and anchored in the dark water. Tall and slim, Manning has sharp features that glow, which seems more a reflection of his boyish spirit then an indication of the cold. His blue eyes are focused on readying his dory for departure. He wears a scarf and two jackets above, khaki trousers below; his grey hair is hidden beneath a green wool cap, though his ears remain exposed to the winter nip. The scarf was long deemed superfluous by Manning, but after years of prodding by his wife Susan, who rows with him, he has relented.

Sam and Susan Manning use poles to break the harbor ice surrounding their dory. The ice bends and sinks under repeated thrusts; eventually, sheets of the inch-thick ice pop free and are pushed beneath the larger mass.

“Some days we only have an hour and we spend it in the inner harbor,” says Sam Manning, “but we’d rather have the time in the boat than not.”

Over the past year, the Mannings estimate they have rowed 300 days. As impressive as the figure sounds, they relate the number with a caveat: They lost valuable time when Susan came down with pneumonia, and then Sam cracked a rib. For 32 years they have been plying midcoast Maine waters in their dory.

Sam’s breath curls into the brisk air as he sculls, in reverse, navigating the narrows between the wharf and the float before settling down to the oars to row into the silent harbor.

Manning’s dory, in the shop for maintenance and repairs.

Manning’s dory, in the shop for maintenance and repairs.

Though his physical aptitude alone is cause for admiration, Sam Manning, who has logged enough miles rowing and sailing a dory to rival any Grand Banks fisherman, is a Renaissance man with many traits and talents worth admiring. For as long as the many winters he has chipped his dory free of harbor ice, Manning has been a nationally recognized illustrator of marine books and periodicals, and the author-illustrator of many works of his own. Hundreds of pages have been graced with the precise and humanistic style that has become his signature. He is also a master craftsman who believes ardently in the virtues of hand tools. He has built countless homes, boats, and beyond. Attention to detail and reliance on found materials, from telephone poles to driftwood, make his building projects unique. He is well known for his knowledge of maritime history and is regularly consulted by authors and editors. On quiet afternoons, he picks up a harmonica and lets his mind wander.

Manning is known for a willingness to share his talents. Those that express curiosity in his areas of proficiency will be treated to the pleasure of his company and the expertise of his steady hand. He has a soft spot for precocious youngsters who remind him of a certain someone who came of age on a northeastern farm during the Great Depression.

A master craftsman who has an ardent belief in the virtues of hand tools.

A master craftsman who has an ardent belief in the virtues of hand tools.

As a young boy, Samuel Frothingham Manning was first exposed to the world of boats by observing sailing and motor craft of every design glide to and fro across Long Island Sound from his seaside summer home. But it wasn’t until 1937, age seven, when he had moved inland with his mother and stepfather to a farm with a five-acre pond in Colebrook, Connecticut, that his passion for boats was born. His mother, a biplane pilot and draftswoman, believed that her family would learn self-reliance in a rural setting. Her son remembers the farm as a “great experience to grow up in.”

The adolescent Manning became intrigued with watercraft by venturing onto the pond, but removed as the farm was from the sea, he was on his own.

“If you wanted a boat,” he said, “you had to make it—invent it all yourself.” The lion’s share of the design work was squarely on his young shoulders. He worked from photographs but found them less than satisfactory, as they lacked a complete view of the all-important hull.

“My heart goes out to young people who try and do this,” he said. “Helping them learn how to make something is important.”

Manning was fortunate. He lucked onto a mentor, a local carpenter who helped him lay out a 5-foot version of a garvey, a flat-bottomed workboat. Soon, Manning’s days were filled with paddling, poling, rowing, and sailing across the pond.

While living on the farm and attending the local one-room schoolhouse, Manning read Captains Courageous by Rudyard Kipling, the story of a spoiled boy who gained his maturity at the hands of real work aboard a fishing schooner. Manning found the book gripping, the tale mythical against the backdrop of his landlocked farm.

Back on the pond, Manning came to appreciate how effectively a sail could carry a boat in a breeze. On windless days, under the tutelage of his stepfather, an engineer and architect, he learned what could be accomplished by sculling. Forget motors; Manning would master oar and sail. On the farm his enthusiasm for boats had grown indelible.

By the time he was in high school, during World War II, the Manning family had moved to Laguna Beach, California, where his parents took jobs in the war industry. Here, Manning’s knack for drawing began to shine as he was exposed to “how people are supposed to draw” in that artist-rich town.

Manning’s ability to render ships under sail with accuracy and emotion caught the attention of his art teacher, who, during Manning’s senior year, requested that he illustrate the class yearbook. In the drawings—all of boats, of course—the familiar Manning panache is present. His boats are anything but stagnant; rather they are heeling over with sails filled to bursting and rails buried as the sea arcs high and clouds cloak the sky. His creations are all the more noteworthy when considering that, at 18, he had undergone next to no formal training as an illustrator. He had influences, however. He was drawn to the work of two artists in particular: Rockwell Kent and Gordon Grant, whose styles were striking but nearly opposite. He admired Kent for the stark reality and impact of his work, and Grant for the humanness and fluidity of his.

While in high school Manning worked as an apprentice to a boatbuilder who built the Pacific 14, a plywood takeoff of the International 14. After high school he joined the Navy, where he learned that he didn’t want to be an enlisted man all his life. A year later he was working for Henry B. Nevins Yacht Builders in City Island, New York, and then, in 1950, entered Bowdoin College. He “spared” his father the cost of tuition by utilizing the G.I. Bill, which he supplemented with his work as a boatbuilder and carpenter. But his studies were interrupted during the Korean War, when the Navy called him to active duty from the inactive reserve. He then spent two years as a quartermaster second class aboard an LST landing craft, where his service ranged from the Caribbean to Greenland. He perfected his navigation skills in his spare time.

Sam Manning came from a long line of engineers and was inclined to follow suit when he returned to Bowdoin College, yet he was discouraged by a professor who recognized his difficulty with numbers.

“I could visualize spatial relations,” said Manning, “but I couldn’t assign numbers and have them add up to spatial relations. My brain just didn’t work that way.” Yet to look at Manning’s life 50 years hence it is clear that an engineer’s mentality has been at work.

Susan Manning is quick to point out that her husband is truly an engineer at heart. “He’s very innovative,” she said, “If something’s not working, he’ll find a way to make it work.” His talents and creations speak this truth.

The Mannings’ home is a testament to Sam’s cleverness. He and Susan did all the renovations themselves on what was originally a three-bay garage with a light apartment. Beams came from telephone poles that Manning hand-hewed; posts were salvaged from a demolition site. Driftwood was the source for the joists. The basement was dug by hand, a gargantuan feat when one considers that there was ledge to contend with.

Sam Manning’s craftsmanship is all the more impressive when you consider that he uses hand tools alone. The front door is opened via a wooden latch-and-cam system that he built to “avoid buying some brass thing.” As you climb the steps to the upstairs living quarters a block and tackle system for hoisting firewood hangs overhead. An accessory to his drafting table—a 4-foot by 8-foot piece of worn plywood—is a pair of homemade magnifiers for working on his detail-rich illustrations.

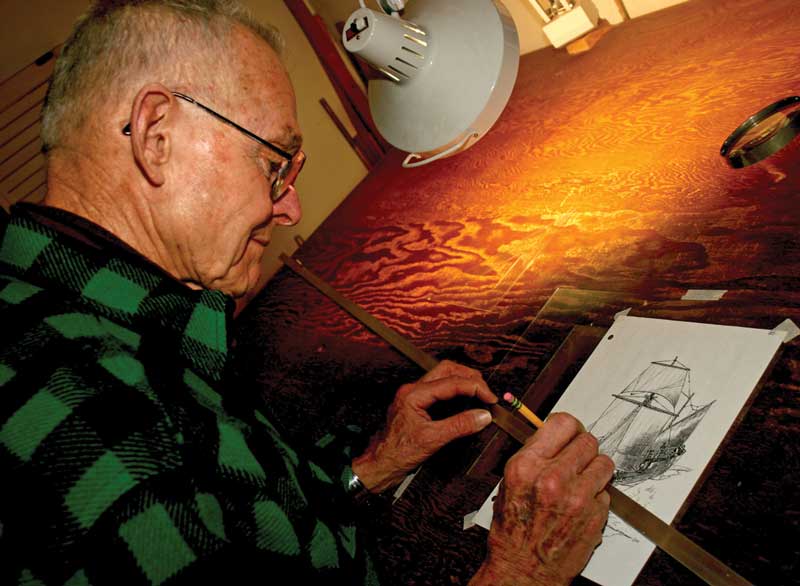

SManning has a penchant for accuracy, an ethic that is apparent in his illustrations.

SManning has a penchant for accuracy, an ethic that is apparent in his illustrations.

Manning’s ingenuity is also present in the way he creates his illustrations. He devised his own method of measured perspective drawing, whereby he traces two adjacent lines to a common vanishing point on the outskirts of his drafting table. He then places a pin at this point, which becomes the fulcrum for a handmade Plexiglas straightedge. The straightedge is then used to draw or check his lines. At the time of his devising he was unaware of anyone else using a measured perspective system to draw boats.

Today, Manning generally begins his drawings freehand and relies on a straightedge for correction. He said that his drawings are about “helping someone get over the hurdle of visualizing something.” His favorite jobs, he said, involve historical illustrating, where he breathes visual life into the words of historians. He said that he learned early on that his drawings were lifeless without the addition of people and animals. He understands how to turn words, numbers, and plans into three-dimensional drawings that grab the viewer with a precise and comforting familiarity. He is gifted at drawing what the eye sees.

A straightedge is used to manage the proper perspective.

A straightedge is used to manage the proper perspective.

A proper Renaissance man would be lost without adventure, and Sam Manning is no exception. The summer before he graduated from Bowdoin College, he and a friend from the Navy ventured forth on a memorable journey. They set sail from Brunswick, Maine, in a 23-foot open dory rigged with two sails, determined to reach Newfoundland. With axe and shovel the previous winter, Manning had liberated the dory, which had been abandoned, from the frozen beach at Reid State Park. He replaced the garboards and transom, made a centerboard, and outfitted the craft for sailing.

Although they didn’t reach Newfoundland due to the tumult of Cabot Strait and the looming academic year, the dauntless pair rowed a quarter of the 1,000-mile trip. They accomplished their goals of testing the value of a dory as a sea boat and experiencing firsthand the boatbuilding and fishing culture of maritime Canada. Near the end of their 70-day epic voyage, while attempting the crossing, against the advice of locals, from Cape Breton to Newfoundland, they endured the worst northeaster of the season. Manning, who had to suffer through the only bout of seasickness of his life, steered the dory tirelessly for 15 hours; they were forced to bail constantly while dealing with 40-mph wind, 20-foot swells, and a night as black as coal.

Today Manning looks back on the voyage as “a meaningful experience in college” that taught him that a small boat could go almost anywhere if you are willing to make the effort. It led to visions of sailing around the world, but too soon college and then earning a living put an end to such a dream.

Manning remembers the 1950s as a time of conforming, when “everybody had the idea of being a vice-president some day.” After his graduation, he followed this avenue for a few years, first as a management trainee for the American Export Line in New York and later with his father as a salesman for the Alexander Hamilton Institute, which sold a 26-volume business administration program. He became the top salesman in New England his first year, but felt suffocated by the urban environment and found himself “telling people what to do when you didn’t believe it yourself.” So he returned to Connecticut, where he met and married his first wife, and went to work as a boatbuilder and carpenter.

In his spare time Manning built an 18-foot canoe for a trip along the southern shore of Newfoundland. In 1961, while heading north, the young couple ran low on money and decided to winter over on Cape Breton. Here Sam decided to teach himself how to write and draw for publication. He discovered that if he provided illustrations he could sell an accompanying story and soon garnered interest from the National Fisherman for an article about Canada’s federally funded fishing boats. One article led to a second, but he quickly learned that illustrating alone was the most efficient way to earn an income.

Manning says that he began taking illustrating seriously “when I started getting hungry.” Despite his obvious talent, he is humble, even self-effacing, about his skill. “Some people have a natural flair for drawing,” he explained, “I’m not sure that I do. It’s a skill, like many others, if you need it you begin to explore how to do it better.”

In Cape Breton, Sam Manning discovered the illustrations of C.W. Jefferys, who had a knack for conveying human figures and expression. He strove to place his own work somewhere among the three styles of Kent, Grant, and Jefferys. “Any schooling I’ve had [has come from] reading books very carefully,” he said about his training in illustration.

Manning’s talent rests atop a foundation of experience with his subject. Susan Manning recalled that the most meaningful compliment Manning had ever received was from an old timer who praised him by saying “You’ve been there” after looking at his illustrations.

Over the years Manning has established himself as an illustrator by working for magazines, builders, architects, and advertisers. In his early years he contributed regularly to the National Fisherman; later, he established a lasting relationship with WoodenBoat magazine. He has done boat design work and is always working on another set of book illustrations. On occasion he still writes articles related to fishing or boatbuilding, but drawing has become his primary occupation.

In 1969, now a father, he moved from Connecticut to Camden, Maine. Later, in the mid-1970s, following a divorce, he took a job running the shop at the Penobscot Boat Works in Rockport. After hours, he built a boat for himself. He took the lines off an old fish-trap dory and modified them to his liking. He cut in some sheer for stability and installed a centerboard; 20 feet was the right length, any shorter and it would be tender, any longer and the wind would blow it around. The result was a craft akin to a two-man Banks dory.

In an effort to get some orders for the shop, Manning took his new dory, which he named Hopeful Outlook, to the Mystic Small Craft Workshop in the summer of 1975. That was when and where he met Susan. That was also when and where the Traditional Small Craft Association was established, with Manning playing a leading role. The group, now an international organization dedicated to spreading the virtues of traditional watercraft, came together to counter pending Coast Guard regulations that they feared would ruin the traditional boatbuilding industry. Largely as result of the TSCA, the regulations were revised.

Since 1975 Manning has been employed entirely as a freelancer. How? “One job bred the next,” he noted simply, and then said jokingly that come real-estate tax time a home with a single bathroom and tarpaper “Tudor” siding allows him to remain self-employed.

The artist/craftsman, and his wife Susan, the “knotwright.”

The artist/craftsman, and his wife Susan, the “knotwright.”

The Mannings’ approach to living emphasizes the present and leans toward the active. They have no television or computer and do not drink alcohol. Reading aloud and listening to the radio are common early evening entertainments. The couple is granted freedom during daylight hours because Sam prefers to work at night.

“I go backwards during the day if I do writing or particularly illustrating,” he explained. He starts work after dinner and continues until 2:30 or 2:45 a.m. “If it’s getting dark, I’m not molested by what’s going on [outside] and that’s when the concentration sets in.”

Daylight is time for physical activity—building something, digging a hole, rowing the dory. Manning’s current daytime projects include redoing the rails on the dory and tending to the ongoing renovations of his home (he plans to move their kitchen from the second to the first floor and add a second bathroom—don’t tell the tax man!).

He said that he gets grumpy and easily tired when he and his wife miss their exercise. He likes winter rowing because of the dynamic weather and the lack of congestion in the harbor.

How has rowing shaped his life?

“Rowing brought Susan into my life,” Manning said in a reflective whisper, adding that he uses the time at the oars to think through his day’s work and enjoy nature.

“It’s better than church,” said Susan.

Sam Manning proudly refers to Susan as a knotwright for her aptitude with rope: curtains sewn from sail covers, doormats made with coiled line rescued from the dump, an intricate sleeve of twine used to strengthen the cracked handle on a ceramic mug, canvas handbags neatly darned. When her handiwork is combined with the dark, open, rough-hewn post-and-beam interior of their residence, the ladder descending to the basement, the garments hung in one corner of the downstairs, the boxes of old WoodenBoat magazines neatly stacked in another, visitors can’t help but feel that they’re in the cabin of a sailing ship.

Once when Sam Manning was asked if he saw himself as a nineteenth-century man, he said, “I probably wanted to be an eighteenth-century man, mostly because I admire human skills. Today’s skills are very different. What I see is all of us having to live a life that is very conforming—daily jobs that aren’t all that interesting, but we have interests on the side that relate to our nature of wanting to make things for ourselves, and this is where I feel like I can help people.”

Sam Manning has taught classes at the WoodenBoat School and the Apprenticeshop when it was in Rockport. Reflecting on that, he said that he believed in the value of creating something entirely by oneself. “I think it’s important,” he said.

Susan recalled her fascination with Native Americans as a child. She said that her husband never shared that interest because, she explained, “You couldn’t get a sharp edge on a stone tool.”

“So my interest starts in the Iron Age, doesn’t it?” Manning joked. “I like the nineteenth century from the perspective of the twentieth century,” he concluded and added that the hardships of centuries past was beyond what he would care to endure.

The Mannings agreed that they live in the best of both worlds, with the luxury to pick and choose. They can live a simple life while also benefiting from the modern conveniences allowed by electricity, medicine, and their 20-year-old truck.

“Someone like me would have no teeth at this point,” Manning said in praise of modern dentistry. “I wouldn’t want to give up my tetanus shot,” added Susan. Clearly, the Mannings aren’t traditionalists to a fault.

Sam Manning has a penchant for accuracy, an ethic that is apparent in his illustrations, which he described as “not art, as such—art is expression, a way to see or feel. This is meant as accurately as consensus will have it.”

He consults with other historians and designers to perfect his work. Yet the notion that his drawings are not art or that the emotion that they possess somehow detracts from their authenticity does not hold. His tendency to lean toward the precise seems only to emphasize his skill and artistic ability: with his hands he renders a subject so true to life that it begs our attention. How could this not be art?

But as anyone learns who spends time with Sam Manning, one of his several endearing qualities is his modest nature, void of boasting. Perhaps because of his fervor for accuracy he admits out loud his own imperfections, which to his admirers are hardly worth mentioning but to Manning, it seems, they must be revealed lest we hold him in too high esteem.

A Sam Manning drawing from The Dory Book.

A Sam Manning drawing from The Dory Book.

Sam Manning has illustrated 23 books and published dozens of articles over his career, and his productivity shows no sign of slowing. Current projects for WoodenBoat magazine and others still keep him up past the bedtime of most.

Although praise is second nature when it comes to Manning’s work, one accomplishment in particular, The Dory Book, published in 1978, has come to hold special significance in the hearts of small boat enthusiasts. For that he teamed up with builder and small craft guru John Gardner. Reissued in 1987 by the Mystic Seaport Museum, where Gardner was a curator until his death in 1995, The Dory Book is respected by all who have read it as “the” definitive text on the history and building of the dory. Manning’s illustrations in it are clear, detail-rich, and atmospheric.

The dory as an object and a concept runs straight through Sam Manning’s life. The dory is derived from simple, effective design, constructed with common materials, and built to be a stable, sturdy, and highly seaworthy craft. The man affects the boat, the boat affects the man.

So, too, has Sam Manning affected the lives of others. Kindly interactions often become friendships. Nathan

Spectre, of Belfast, who grew up near the Mannings in Camden, tells how he couldn’t help noticing the curious neighbor who was nightly hallowed in the light of a second story studio window until early morning. In high school, Spectre sought out Manning’s assistance in sharpening an old plane, and a friendship blossomed.

“He’s a one-of-a-kind person,” said Spectre, who builds and designs homes, and who named a son after Manning. “I think of him when building something. He uses common materials, often salvage, but is very precise. Most people change routines, but Sam’s done the same thing for a long time.”

Rob Eddy, of Camden, a respected builder of fine yacht models concurred. “Sam is gifted in so many different ways,” he said. “His drawing abilities are beyond most all others today.”

At age 12, Eddy was introduced to Manning when the illustrator helped him turn sections for a Hinckley Pilot 35 into a set of line drawings. He credits Manning as a mentor who inspired him to pursue model building.

“If he knows you’re interested,” Eddy said, “he’ll take time to make sure you understand,” noting that Manning freely shares his talent with friends and strangers alike. “He stands out as one of those exceptional people who strives to do the best he can all the time. I look up to him as one of the most talented people I know. I’m so thankful I had the opportunity to learn what I did from him.”

“We’d rather have the time in the boat than not.”

“We’d rather have the time in the boat than not.”

In a National Fisherman article written in 1964, Sam Manning reflected on the virtues of plying the open ocean in a dory: “You might like to regain freedom with a dory. Reliance upon oars for auxiliary power puts challenge into the game. The sea is frontier when no motor is carried aboard.”

Some might say that, in the twenty-first century, electing to turn ocean into frontier—or to have a hankering for hand tools or to draw illustrations without a computer—is to make life more difficult, more complicated, or even more dangerous than necessary. Yet for Sam Manning it is more about maintaining the appropriate quality of life, where a generation-old routine can bring freshness to each day.

At 77, Manning accomplishes more in the average day than men half his age. He rows, he socializes, he shares his knowledge, he spends time with his wife, he tends to yard chores, he repairs a boat, he keeps up with those ever-present house renovations, he writes a few letters, and then finally he gets to work. If you happen upon him during his day he is never rushed or preoccupied. Rather, he is simply living.

Donnie Mullen is a writer, photographer, and paddler who lives in midcoast Maine.