Dear Friends:

Here we are at the first week in November and still waiting for a hard freeze. Though the oaks and beeches are still holding on to their leaves, most of the other hardwoods are losing theirs or have lost them. The hackamatacks are glowing gold in the fading sun and the blueberry barrens are turning to copper and magenta. The grasses of the field are turning brown and lying down for a long rest—but the grass is still green, sunflower seedlings are sprouting under the bird feeders, Queen Anne’s lace is still in bloom, and so are the nasturtiums.

Migratory report, November

At this season there are few sights to entertain the eye and few sounds to fill the heart more fully than those of a flock of Canada geese (Branta canadensis) flying south for the winter. First comes the faint sound of honking through the trees. Then, the vanguard of the “V” appears overhead with massive wings beating, webbed feet tucked up tight and long necks stretched eagerly ahead. Then, it widens out into two long parade lines and we can hear the rush of wings through the honking of dark flyers. The performance is so mythic that it may awaken our own latent migratory urges so we want to rise and join the flock coursing over the orange and yellow hills.

From the geese we derive lessons in navigation, courage, cooperation, and leadership. It is said that the bird at the head of the “V” takes turns with other members of the flock. If the head bird gets tired, or wavers, or wanders off course another bird will move up to take its place in a change of leadership for the sake of the flock. How it is decided who will take over in this peaceful transfer of power is something we do not know. They cannot fight for first position because they are on the wing and a smooth flight is essential lest the flock be endangered. Then, when it gets tired, the new leader drops back and another takes its place. Somehow the leader must know when to press ahead and when to bring the flock down for food, water and rest at various places along their way southward. In this ancient way, thousands of Canada geese make their way south for the cold months and then north again in the spring.

Natural events

November also means deer season with all that entails. Hikers now put on blaze orange, some willingly, some reluctantly. If hunting season rubs you the wrong way, here are a few upsides of hunting to consider: Some of the greatest conservationists have also been hunters. Think John James Audubon, Teddy Roosevelt, and Aldo Leopold, for examples. Hunters know the woods as few others do, especially if they have been hunting there all their lives, and they will work to preserve the wilds.

Meat taken by hunting has a lower carbon foot-print than meat raised commercially. For every pound of game, there is a pound of beef or chicken that will not be fed expensive feed, shipped to the supermarket to be wrapped in plastic, and its remains taken to the dump. Game meat is lean, organic and local, probably much healthier than store-bought meat. Good hunters have a strong ethic around wild game which includes a fair chase and a clean kill, tracking down a wounded animal, sharing meat with those who are unable to hunt, and loathing bad hunters. It is a spirit of respect and generosity that marks the traditional hunter.

Illustration by Candice HutchisonThankfulness report

Illustration by Candice HutchisonThankfulness report

Thanksgiving is nearly a universal practice. You would be hard put to find a culture or religion that does not gather to feast and give thanks. That is because giving thanks is a healthy survival practice, too. It acknowledges that we depend on the soil, the sun, the water, and other living things for our own lives. We do not carelessly destroy those things we are grateful for. Together we honor and protect them, taking only what we need, thereby preserving them for future generations.

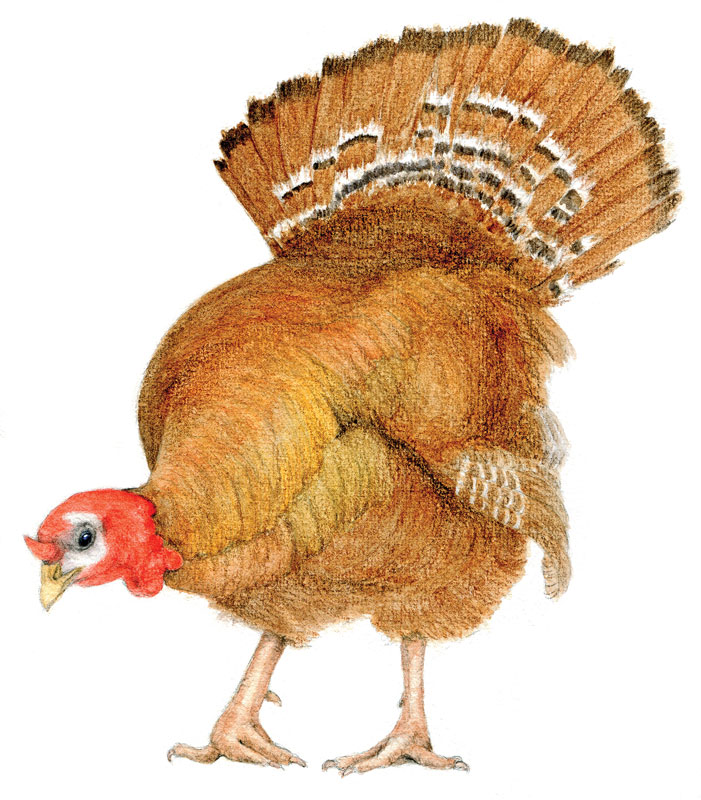

Case in point and star of the season: the wild turkey is a conservation success story. Once hunted out in New England, restocking was begun in the 1950s and now we see them often in the woods and along the road, if not on the dinner table. The Maine wild turkey population is estimated at 70,000.

Field and forest report, December

The Great North Woods or boreal forest is made up largely of evergreens, which have distinct advantages over deciduous trees in a cold Northern climate. The favorite of this season is balsam fir because of its deep green color, its silky needles and its captivating aroma.

Wherever there are balsam fir trees here in Maine, wreath-making time has been in full swing. Tippers come out of the woods with bundles of fir tips, the last two years of growth, clipped from the branches of these fragrant trees. Tips are bundled together and sold by the pound to wreath-makers who swiftly turn out these seasonal trophies to be ready as soon as Thanksgiving is over. There is an art to layering the tips around a hoop and wiring them in place so no winter winds can scatter them, because it’s traditional to keep your wreath on the door all winter. We need that touch of green through the gray and white months ahead. This is how we manufacture hope in the dark time.

Field and forest report II

That bright red berry you see tucked into window boxes among the green fir boughs or growing in wet places alongside the road is Winterberry (Ilex verticillata), also known as Canada holly, or Fever bush. It is native to New England and the Maritimes and is related to the familiar English holly, though winterberry has smooth leaves that it loses in the fall. Winterberry also provides a much-needed food supply to many species of birds during the cold. Flocks of robins feeding jubilantly on winterberry—maybe even getting a little tipsy—during the cold, dark months when there is little else to eat; the quiet hillside filled with their joyful chirping.

Natural events

Lights are a blessing of the season. As the curtains of night are daily drawn more closely around us and the sun crawls over the tree tops later and slips beneath them earlier every day, we break our fast in twilight and eat our supper in the dark. Naturally, we light the lights. Electric candles appear in windows along the streets. Then, a white and gold electric angel magically alighted from the heavens on the huge elm stump in front of our neighbor’s house. One morning the old stump was bare, and by evening there she was standing with hands clasped, wire wings poised.

The dark and cold can be dangerous to the lonely hunter or traveler, but they can be just as dangerous to the lonely homebody. Fear, gloom, and depression may creep in with the cold drafts under the door. Rugged individualism can quickly turn from a virtue to a vice these days. That is why we humans have gathered through the ages with our tribes to light the fires, sing the old songs and tell the old stories at this season of the year. No one commands us to do these things. No orders come down from on high. We simply follow the ancient practices and wisdom of our hearts. It matters not so much with what tribe we gather, what lights we light, or what songs and stories we chant. They have been many and various through the ages. But it matters greatly that we do it. Our gatherings, our lights, our songs will signal the choirs of angels where to flutter down to land all over the planet, so the whole world can give back the song that now the angels sing, “Peace on Earth. Fear not, fear not.”

Seedpod to carry around with you

From Rabbi Lawrence Kushner: “The days have been growing shorter, imperceptibly but inescapably darker. Heading into the night of the winter solstice, every religious tradition has some sort of festival of light. We’re all just whistling in the dark hoping against hope that someone up there will see these little candles and get the hint.”

That’s the Almanack for this time. But don’t take it from us—we’re no experts. Go out and see for yourself.

Yr. mst. humble & obd’nt servant,

Rob McCall

✮

Rob McCall (1944-2023) lived in Brooklin, Maine. The selections in this almanack were excerpted from his archives.