Alexandra Conover Bennett holds an unnumbered North Woods Paddle she carved 30 years ago. Paddles that didn’t meet her rigorous standards went unnumbered and were incorporated into the stores of her former guiding business. The paddle shown is an ash bow paddle, five feet in length, and a veteran of countless canoe trips from Maine to Labrador. It’s now her favorite paddle for crossing the lake near her home. Photographs By Donnie Mullen

Alexandra Conover Bennett holds an unnumbered North Woods Paddle she carved 30 years ago. Paddles that didn’t meet her rigorous standards went unnumbered and were incorporated into the stores of her former guiding business. The paddle shown is an ash bow paddle, five feet in length, and a veteran of countless canoe trips from Maine to Labrador. It’s now her favorite paddle for crossing the lake near her home. Photographs By Donnie Mullen

In the north, a canoe and paddle constitute traditional travel. That phrase, traditional travel, ignites a romantic cascade of imagery and sensation: the soft creak of a wood-and-canvas canoe under way, droplets shed from a wooden paddle’s blade, the sweet smell of an unwashed cotton bug shirt—all this set within a quiet landscape.

This world so intrinsic to Maine’s rich outdoors heritage recently witnessed the passing down of a revered tool. The tool, in this case, is a paddle. Wilderness guide and craftswoman Alexandra Conover Bennett decided to retire after 38 years of carving her prized North Woods Paddles. Shaw & Tenney, the Orono-based wooden paddle and oar maker, was the lucky recipient of her patterns.

The story of the paddle, its transfer, and the ancient practice of the North Woods Stroke, is a good one.

“The best part of the project was spending time on the water with Alexandra,” said Steve Holt who, with his wife Nancy Forster-Holt, is the third family to own Shaw & Tenney during its 162 years of operation.

Holt, and Sam Martinelli, Shaw & Tenney’s lead paddle maker, spent half a day with Bennett, talking shop and trading stories. When Holt asked Bennett—a natural-born educator—to teach them the North Woods Stroke, it’s hard to say who was more excited, Bennett for the chance to pass on her knowledge, or Martinelli to receive it.

“It meant a lot to go out with one of the greats,” said Martinelli, who was seven years old when his parents took him on his first canoe trip.

Bennett uses a crooked knife to carve the graceful chamfered edges on the grip of a North Woods Paddle. Traditionally, an axe and crooked knife were the two tools used to carve a paddle.For nearly 30 years, Bennett—a registered Maine Guide since 1978—co-owned North Woods Ways, a guiding service that specialized in traditional canoe and snowshoe travel in northern Maine and Quebec.

Bennett uses a crooked knife to carve the graceful chamfered edges on the grip of a North Woods Paddle. Traditionally, an axe and crooked knife were the two tools used to carve a paddle.For nearly 30 years, Bennett—a registered Maine Guide since 1978—co-owned North Woods Ways, a guiding service that specialized in traditional canoe and snowshoe travel in northern Maine and Quebec.

Bennett grew up in a family that appreciated old things. She paddled her grandparents’ wood-and-canvas canoes and used her father’s hand tools to construct bows and arrows, tree houses, even hammered dulcimers. At College of the Atlantic, in Bar Harbor, Maine, she studied the traditional craftsmanship of the Maine woods, led canoe trips with her classmates and, in 1977, during her senior year, met Maine guide Mick Fahey who lived in remote Chesuncook Village. Fahey recognized Bennett’s aptitude and here began a mentorship that lasted until Fahey’s death in 1985. Early on, he taught Bennett how to carve an axe handle with a crooked knife.

“Axe handles are extremely fussy,” explained Bennett.

When he asked her to make some paddles, Bennett took two of Fahey’s and sketched patterns on paper bags. Thus was born her version of the North Woods Paddle. Typically made from native white ash—chosen for its workhorse blend of strength and flex—Bennett’s paddles combine elegance with utility. The sizable flared grip offers a visual complement to the substance of the beaver-tail blade and considering the fact that a stern paddle could be as long as its paddler is tall, her creations carry substantial presence.

Years later, Bennett came across drawings in Edwin Tappan Adney and Howard I. Chappelle’s Bark Canoes and Skin Boats of North America of an 1889 Passamaquoddy ocean paddle and an 1896 Malecite paddle from Maine and New Brunswick. She found the two paddles’ wide, elongate grips to be a close facsimile to Fahey’s paddles. This “guide grip”—popular until the 1940s—gives the paddler a separate grip whether they kneel, sit, or stand.

Patterns for mini paddles, canoes and oars that are most often used as awards in canoe races.

Patterns for mini paddles, canoes and oars that are most often used as awards in canoe races.

Over her career, Bennett carved, signed, and numbered 552 North Woods Paddles. She remains particularly proud of her blade tip design.

“It’s about the only thing I’ve contributed to paddle shape,” she said with a modest chuckle.

The thinnest part of her blade resides four inches inland of the tip and thereafter the blade gradually thickens toward a subtle finial bulb. This reinforcement reduces checking and produces less torque under water.

In 1950, Shaw & Tenney relocated to its current location on Water Street in Orono. A small showroom and the woodworking shop are found here. One of the lathes has been in continuous operation since the shop’s inception in 1858. The slab saw and cornering saw date back to the 1890s.

In 1950, Shaw & Tenney relocated to its current location on Water Street in Orono. A small showroom and the woodworking shop are found here. One of the lathes has been in continuous operation since the shop’s inception in 1858. The slab saw and cornering saw date back to the 1890s.

Since arriving at Shaw & Tenney, the North Woods Paddle has undergone a few subtle changes. One is a thinner overall blade. Another, an oval shaft—Bennett carved hers round—that Holt said is a comfort to the hand. He believes these changes will result in a paddle with more flex. Still, Martinelli has incorporated Bennett’s key refinement in his version of the North Woods Paddle.

“I’ve begun to leave a little more wood on the tips of my paddles,” he explained.

Martinelli and Bennett share a laugh while trading stories about Chesuncook Village, a tucked away gem in Maine’s North Woods that they both hold dear. Martinelli holds the 12th North Woods Paddle that Shaw & Tenney has carved since taking over the design. The graceful chamfered edge of the paddle’s grip is a detail that remains unchanged between the two generations in paddle design.

Martinelli and Bennett share a laugh while trading stories about Chesuncook Village, a tucked away gem in Maine’s North Woods that they both hold dear. Martinelli holds the 12th North Woods Paddle that Shaw & Tenney has carved since taking over the design. The graceful chamfered edge of the paddle’s grip is a detail that remains unchanged between the two generations in paddle design.

When Bennett, Martinelli, and Holt took to the water in a pair of wood-and-canvas canoes, Bennett demonstrated the North Woods Stroke, which she considers more efficient than the modern J-Stroke used by many canoeists today. A notable feature of the former is that during its power phase the paddle shaft is positioned diagonally to the water’s surface. Martinelli said that his own style feels clunky after watching Bennett.

“She has a faster cadence,” he noted. “And she uses her body to push the paddle through the water.”

While both Bennett and Martinelli craft their paddles by hand, the process used at Shaw & Tenney involves a few more power tools, such as a router, slab saw, and drum sanders. Even Bennett, after several years of using only hand tools, added a band saw and electric planer to her repertoire.

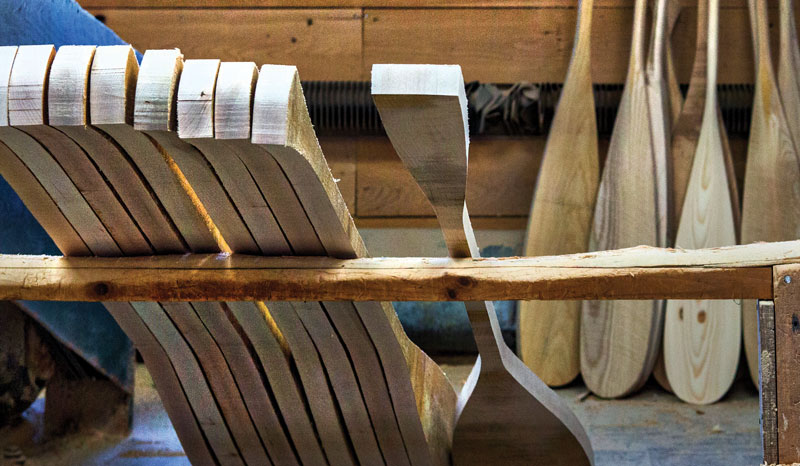

Rough cut Penobscot model paddles (left) and a single rough cut Maine Guide paddle (middle). An assortment of seconds (background) lean against the wall. The Penobscot paddles are part of a larger order for a local camp. Annually, Shaw & Tenney sells paddles to camps nationwide.

Rough cut Penobscot model paddles (left) and a single rough cut Maine Guide paddle (middle). An assortment of seconds (background) lean against the wall. The Penobscot paddles are part of a larger order for a local camp. Annually, Shaw & Tenney sells paddles to camps nationwide.

Bennett once asked an old Algonquin guide if he minded her taking the lines off his paddle. He laughed, and responded, “You do not need to have my permission to make a paddle… used here for hundreds of years.”

In this vein, Bennett passed on her knowledge to Holt and Martinelli at no cost. When Bennett tells this story, she refers to Martinelli as “young Sam.” Her tone is imbued with fondness, yet there’s also a hint of something else, perhaps reverence, even deference. This passing of a time-honored cultural tool between craftspeople is partly a personal exchange, but it’s also a cultural one. What she has cared for lives on.

Donnie Mullen is a writer and photographer who lives in Camden with his family.