All images courtesy Bowdoin College Museum of Art

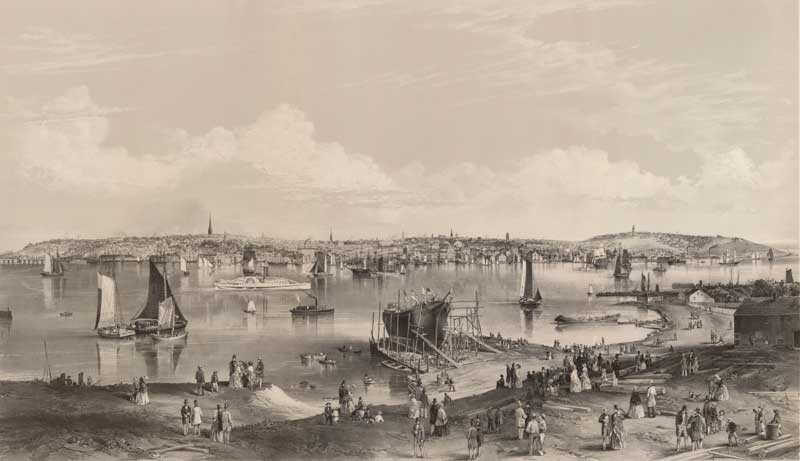

This view of Portland offers an iconic image of the city “at the height of its success as Maine’s largest port.” J. W. Hill, Portland, Me., 1855, Charles Parsons, lithographer. Courtesy Maine Historic Preservation Commission. Photo by Luc Demers

This view of Portland offers an iconic image of the city “at the height of its success as Maine’s largest port.” J. W. Hill, Portland, Me., 1855, Charles Parsons, lithographer. Courtesy Maine Historic Preservation Commission. Photo by Luc Demers

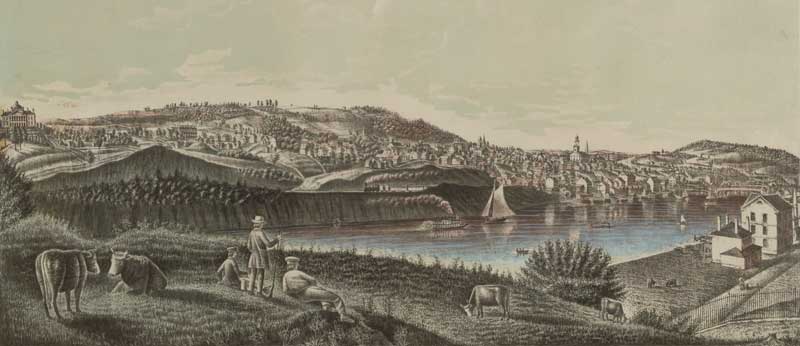

In Franklin B. Ladd’s 1854 panorama of Augusta, three men in the foreground—one seated, one standing, the third lying on his side—gaze across the Kennebec River at Maine’s capitol. They have turned their backs on the bucolic countryside where two cows graze, taken in by the dynamic scene in the near distance.

A steamboat heads upriver, a railroad train chugs south, their plumes of smoke billowing in opposite directions. Beyond, the city is spread out, from the statehouse to the edge of the forest.

A number of the panoramas in the remarkable Bicentennial-inspired exhibition, “Maine’s Lithographic Landscapes, Town and City Views, 1830 to 1870,” on view at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art (through May 31, 2020), offer a similar perspective: settlements seen from a distant prospect. This viewpoint enhances the sense of wide-angle wonder—and accounts for the popularity of these prints, whose subscribers took pride in their home cities and towns and their roles in the growth of a state that had been born in 1820.

Several prints prominently feature boatbuilding activities. John William Hill’s view of Portland from Cape Elizabeth became known as “The Launching Print” on account of the ship-in-progress in the foreground. Published in several variations, the print was sought after as a memento after the Great Fire of 1866. It also served to promote this burgeoning metropolis: In June 1855, The Portland Advertiser noted that the print would “give a favorable idea of us abroad.”

Made at the request of Fitz Henry Lane’s friend and companion Joseph L. Stevens, Sr., whose family lived in Castine, this drawing served as the basis for the lithograph printed the same year. Castine from Hospital Island, 1855, graphite. Collection of Cape Ann Museum.

Made at the request of Fitz Henry Lane’s friend and companion Joseph L. Stevens, Sr., whose family lived in Castine, this drawing served as the basis for the lithograph printed the same year. Castine from Hospital Island, 1855, graphite. Collection of Cape Ann Museum. Fitz Henry Lane’s biographer, John Wilmerding, has called the print “by far the most poetic and sophisticated of his lithographs.” Fitz Henry Lane, Castine / From Hospital Island, 1855, L. H. Bradford & Co.’s Lithography, Boston, published by Joseph L. Stevens, Jr. Uncolored lithograph. Courtesy Maine Historic Preservation Commission.

Fitz Henry Lane’s biographer, John Wilmerding, has called the print “by far the most poetic and sophisticated of his lithographs.” Fitz Henry Lane, Castine / From Hospital Island, 1855, L. H. Bradford & Co.’s Lithography, Boston, published by Joseph L. Stevens, Jr. Uncolored lithograph. Courtesy Maine Historic Preservation Commission.

Fitz Henry Lane’s skinny horizontal graphite drawing of Castine, spread across six sheets of paper, provided the basis for his 1855 lithograph Castine/From Hospital Island. The drawing shows holes along the top where Lane probably pinned it to a wall as he transferred the image to the lithographic stone. He also annotated the drawing with proportional marks, names and colors of buildings, and other details related to the print’s production.

Part of the appeal of some of these panoramas is the remarkably precise rendering of the details. A bird’s-eye view of Brunswick-Topsham from 1877, for example, includes a multitude of small structures spread across the landscape—and what seems like every tree. Bowdoin College appears in the view and, as host of the show, gets its own wall.

The exhibition covers a lot of Maine, from Saco and Biddeford to Bath, Bucksport, Bangor, and beyond: a scenic view of Mount Kineo on Moosehead Lake. Not all is streets and bustling harbors. Case in point: John Bradley Hudson, Jr.’s idyllic depiction of Lewiston Falls, based on the painting that is in the Farnsworth Art Museum collection and which is on loan here.

The show is one more feather in the cap of Earle Shettleworth, who brings all his historical expertise—in Maine art, architecture, culture—to bear on this engaging display. Maine State Historian and long-time director of the Maine Historic Preservation Commission—he stepped down in 2015 after nearly 40 years at the helm—Shettleworth continues to be a champion of many things: beautiful buildings, sites resonant with history, and the materials that preserve Maine’s heritage. In this Bicentennial year, he is busier than ever. Whether it’s an appearance on Maine Public Radio’s Maine Calling—“Give us a history lesson, Earle,” host Jennifer Rooks asked her guest—or organizing this show, he is helping Mainers to understand the history of our state.

Augusta became Maine’s capital in 1827. By the time this print was made, its population totaled around 9,500. Franklin B. Ladd, Augusta, Me., 1854, tinted lithograph by F. Heppenheimer, New York. Courtesy Maine Historic Preservation Commission.

Augusta became Maine’s capital in 1827. By the time this print was made, its population totaled around 9,500. Franklin B. Ladd, Augusta, Me., 1854, tinted lithograph by F. Heppenheimer, New York. Courtesy Maine Historic Preservation Commission.

Although the Bowdoin art museum closed in March in response to concerns over the spread of COVID-I9, you can still see the show. The exceptional catalogue is online at www.bowdoin.edu/art-museum/catalogues/maine-lithographs. You can view all the images in the exhibition accompanied by in-depth captions. The image resolution allows you to zoom in to see even tiny details. A printed version of the catalogue will be available for purchase later this year.

Carl Little has contributed several essays to Chebacco, the journal of the Mount Desert Island Historical Society.

Early Urban Views as Economic Promotion

When Maine’s premier historian Earle Shettleworth began thinking about how best to celebrate Maine’s 200th birthday, he wanted something that would show people today how Maine looked in the early years after statehood.

The printed panoramas of cities and towns that he had been collecting over the years for the Maine Historic Preservation Commission were the perfect vehicle. He had sought out these detailed views of Maine cities and towns from the mid-1800s for their documentary value of the years before photography. He also appreciated their artistic value.

“What I found so interesting was how many different artists both within Maine and outside Maine were responsible for the creation of these views,” he said.

Making the prints was a two-part process. An artist painted or drew a scene, which was then transferred to a lithographic stone for printing. This involved drawing on the porous stone with a special ink that is absorbed and then resists water allowing the stone to be used as a printing plate.

In a few cases the artist and lithographer are the same such as Fitz Henry Lane’s view of Castine in 1855, he said. In others, different artists were involved in the two-part process.

As he began organizing the exhibit, Shettleworth was fascinated to learn more about the artists. For instance, a young woman named Esteria Butler who lived in Winthrop and was connected to Waterville and Colby College (she was married to a Colby professor) painted views of both Bowdoin and Colby in 1836, which were turned into lithographs by Thomas Moore in Boston.

“To uncover her story was very interesting,” Shettleworth said. He learned that she later moved to Georgetown, Kentucky, and in addition to painting a college there, also founded a school for young women at which art and sketching were taught.

The artistic value of the prints was important because in most cases they were presold by subscription to people in the cities depicted, which then covered the production costs.

Maine cities in the years before the Civil War were emerging as important economic centers. These detailed prints showed that. In 1855, for instance, Portland had recently been connected by rail to Montreal and at the same time to Liverpool, England, by weekly steamships. One lithograph from that time was reprinted by a railroad entrepreneur at half size (the sky was eliminated) on thin paper. He commissioned a separate run of the prints in the Maine city. People could fold out the print and see Portland’s economic vitality, Shettleworth explained.

“My overarching goal with this show was to allow people in 2020 to experience how Maine towns and cities perceived themselves, and wished to be perceived in the first 40 years of statehood, prior to the Civil War,” he said. “That was my primary goal, to share these remarkable images.” —Polly Saltonstall