Ready to go with new/old engine and new hydraulics, Amaretto and the author’s dog, Cornwallis, wait for the radio call to come load herring from a seiner.All photos courtesy Joe Upton

Ready to go with new/old engine and new hydraulics, Amaretto and the author’s dog, Cornwallis, wait for the radio call to come load herring from a seiner.All photos courtesy Joe Upton

In the bitter winter of 1976-77, I found myself living in a barely heated house near South Bristol, where I was trying to figure out a way to repower the 71-foot sardine carrier Amaretto (built as the Muriel in East Boothbay for the North Lubec Packing Co. in 1914). My original plan had been to make some money carrying herring around Penobscot Bay and then after a season or so, to take out the 1930s-era Buda diesel and replace it with something more dependable. It didn’t work out that way. The old Buda barely made it to the South Bristol dock. I had to find another engine, like it or not.

The local diesel dealer was eager to sell me the $20,000 Volvo or the trusty $18,000 Cat, but I had money for neither.

Living alone in a town where I knew barely anyone, those were difficult days. Sometimes, after a discouraging day of engine room work disassembling the old Buda, I just needed to walk, to clear the cobwebs and dark thoughts. My wonderful yellow Lab and I would jog down a long lane between snowy fields out and onto a frozen bay. The dog would run across the ice, until he was just a dot in the gathering gloom, then turn around and run past me and disappear the other way. Now and again the ice would mysteriously boom and crack as the tide moved under it, and the dog would return to huddle, frightened, by my side. Then we’d walk back and build a fire in the old farmhouse’s woodstove. I’d feed the dog, heat up something quick for myself, and we’d just sit by the fire together. For then, that was good, and it was enough.

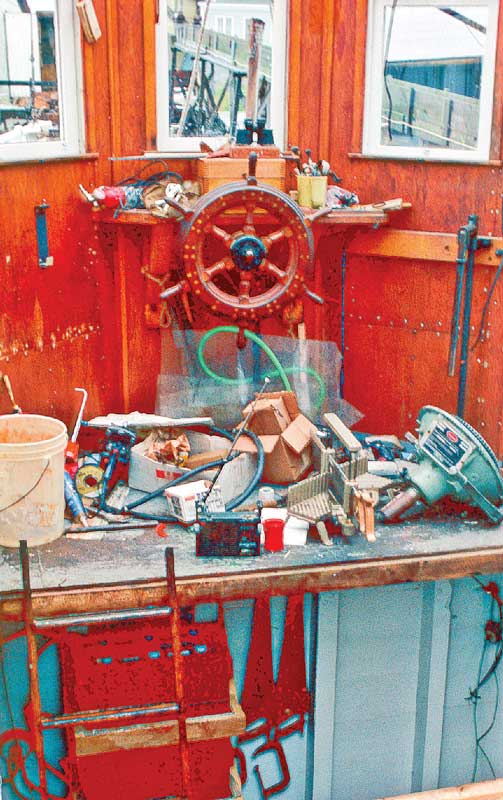

It became apparent how big this project was when the pilothouse came off Amaretto, shown here at the dock in South Bristol. Then in late February I saw an ad in National Fisherman: “Graymarine surplus 6-71, still packed in Cosmoline, $1,500, NH.” I knew those engines—tens of thousands of them had been built to power landing craft and tanks in World War II, and were recycled after the war into fishing boats all around the country. They were simple and dependable. The first boat I’d worked on in Alaska as engineer had a pair of them. Later I ran a fish-buying boat with one.

It became apparent how big this project was when the pilothouse came off Amaretto, shown here at the dock in South Bristol. Then in late February I saw an ad in National Fisherman: “Graymarine surplus 6-71, still packed in Cosmoline, $1,500, NH.” I knew those engines—tens of thousands of them had been built to power landing craft and tanks in World War II, and were recycled after the war into fishing boats all around the country. They were simple and dependable. The first boat I’d worked on in Alaska as engineer had a pair of them. Later I ran a fish-buying boat with one.

I borrowed my friend Lincoln Davis’s 1946 one-ton blue Ford, and headed to a New Hampshire garage where I found my new engine, hooked up to a water hose and a five gallon can of diesel. It had the old-style valve cover. I looked carefully at the governor and there was the word “Battle”—painted over, but still visible. Battle refers to a position on the throttle control that was only used when desperately necessary: headed into an enemy-held beach, the men crouched low, the shells falling fast and furious, when you needed every knot of speed that the engine could possibly produce. If the price was raw fuel burning its way around the rings and into the cylinder linings, it didn’t matter, the engine could be rebuilt later.

We hooked up a battery to the engine, and what a racket—it started right up! Deal done, we called a wrecker to hoist the engine into the back of the truck. The dog and I and that World War II engine headed up the road to new lives for all of us. I figured that if it could push a landing craft of frightened men into a beach at Normandy, Sicily, or North Africa, surely it could push an old sardine carrier along the coast of Maine.

Step one was to get the old Buda out. Seen here, the engine—with the head removed to lighten it— is ready to be lifted out at Hodgdon Brothers Yard in East Boothbay.

Step one was to get the old Buda out. Seen here, the engine—with the head removed to lighten it— is ready to be lifted out at Hodgdon Brothers Yard in East Boothbay.

When I pulled into the local engine dealer’s shop to use his hoist to unload the truck, I sensed that he and the fishermen in there with him saw me in a new light. Another old sardine carrier was also lying at South Bristol that winter, the old Conqueror, whose long-haired owner seemed more interested in tooting weed and telling tall tales than actually tackling the sorely needed rebuild. Until the moment when I showed up in the February dusk with a 1940 engine in the back of a borrowed 30-year-old truck, I sensed that the men had considered me as just another dreamer with an old boat.

The $1,500 for the engine was just the beginning. The pilothouse had to be rebuilt, and the engine needed a reverse gear. The only one I could find was in Seattle: $2,000 plus air freight. When it arrived, it turned out that the 1946 oil pan didn’t work with the 1976 reverse gear. A friend from my Alaska fish-buying days flew out to help with the by-then-immense project. I’d about run out of money.

Fortunately spring came, and the folks around town were sympathetic to our situation: Junior Farrin, whose wharf we were tied up at, stopped by with mackerel from his fish trap and lettuce from his garden, and lobstermen dropped off lobsters. And a minor miracle occurred when the loan officer at the Damariscotta Bank and Trust found the courage to loan money on a boat older than he.

One day, one of the draggermen invited me up to his house. There, spread out on the floor of an upstairs bedroom with a view of the bay, were boxes of original parts for my engine, some still wrapped in wax paper and Cosmoline. There was the oil pan that I needed, a new water pump, and new injectors. “Take what you need,” said the kindly fisherman, “pay me when you can.”

The crane over at Hodgdon in East Boothbay, where Amaretto had been built so many years earlier, hoisted out the old Buda and set it over in the weeds. A few weeks later, with the engine room cleaned, painted, rewired, and replumbed, the crane at Harvey Gamage’s Boatyard hoisted in the new/old Graymarine.

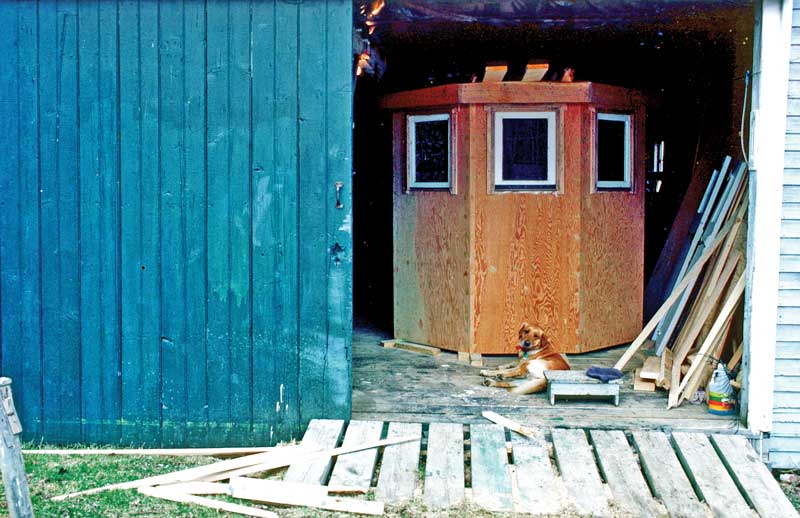

The new pilothouse (with construction chief Cornwallis) in Lincoln Davis’s barn in Damariscotta Mills.

The new pilothouse (with construction chief Cornwallis) in Lincoln Davis’s barn in Damariscotta Mills.

Old Merrit Brackett, crackerjack South Bristol mechanic, heard the engine running rough one day and came over and spent a couple of hours down in the engine room with me, setting the valves and the injector rack, even giving me the special little tool that he used. Thrilled at how much better the engine sounded, I thanked him and asked what I owed him.

“Aw,” he said, “I didn’t do much. Give me five bucks.”

We spent almost the last of the borrowed money on fuel and enough groceries to get out to Vinalhaven where I had heard there might be work for an old sardine carrier.

Where was that new bearing? There’s a reason most folks hire a boatyard for repowering projects.But first we needed to thank all who’d helped us. I borrowed a grill, bought burgers, beer, and chips. And on a perfect early summer afternoon, tied alongside another sardine carrier, the Betsy and Sally, skippered by a friend, Paul Cartwright, we had a party on board the freshly painted, rigged, and repowered Amaretto.

Where was that new bearing? There’s a reason most folks hire a boatyard for repowering projects.But first we needed to thank all who’d helped us. I borrowed a grill, bought burgers, beer, and chips. And on a perfect early summer afternoon, tied alongside another sardine carrier, the Betsy and Sally, skippered by a friend, Paul Cartwright, we had a party on board the freshly painted, rigged, and repowered Amaretto.

One by one, I proudly took everyone down the ladder into the engine room. We hit the starter and slapped each other on the back as that 35-year-old engine rumbled yet again into life.

The leaves were gone from the trees, and the fall winds had started to blow in earnest when I pulled back into our winter berth at Junior Farrin’s dock, after an exciting and finally profitable season carrying herring for bait to lobster buyers on Vinalhaven, Stonington, Swan’s Island, North Haven, and Matinicus.

I put the lines on the dock, shut down for the last time, and the dog and I headed up the road to Christmas Cove for a nice long walk.

On the way, we met one of the many kindly folks who’d helped us get Amaretto going that spring. He asked us how we’d made out and I told him it had all worked out great.

“Good,” he said. “We hoped it would.”

Joe Upton fished in Maine and Alaska for 25 years.

More about Amaretto and the herring fishery can be found in Amaretto, published in 1982 by International Marine Publishing, and reprinted in 2015 as Herring Nights: Remembering a Lost Fishery by Tilbury House.