Harmful blooms can occur in the ocean as well as lakes and ponds. Shown here is a cyanobacteria bloom from Sabattus Pond in central Maine. The clumpy one, called Aphanizomenon, is toxic. Photo by Nicholas Record

Harmful blooms can occur in the ocean as well as lakes and ponds. Shown here is a cyanobacteria bloom from Sabattus Pond in central Maine. The clumpy one, called Aphanizomenon, is toxic. Photo by Nicholas Record

Most kindergartners will tell you that the ocean is blue. But seasoned mariners have often marveled at the ocean’s many other colors. From the burnt green of Samuel Coleridge’s “witch’s oil” water to the “white squalls” of Herman Melville, to Homer’s “wine-dark sea,” each color tells a different story.

What story does it tell, then, when the sea is red?

You might have heard of “red tides.” This is a colloquial term for what scientists call “harmful algal blooms” or sometimes just “harmful blooms.” Many of them do paint the surface of the ocean a distinct color, ranging from orange to brown, or even golden. In 1770, in one of the earliest recordings of a red tide, Captain James Cook wrote: “The Sea in many places is here cover’d with a kind of a brown scum, such as sailors generally call spawn; upon our first seeing it, it alarm’d us, thinking we were among shoals, but we found the same depth of water where it was as in other places.”

Cook was describing the type of algal bloom that has become the focus of research and resource management around the world. Some stain the sea to such an extent that they are visible from outer space, while others leave no visible trace at all.

In Maine, stories about algal blooms have become more common. Much of the coast was shut down to shellfish harvesting the past two falls after blooms downeast. Scientist were monitoring another algal bloom in Casco Bay last September.

Here are three stories about harmful blooms that affect everything from the water we drink to the air we breathe.

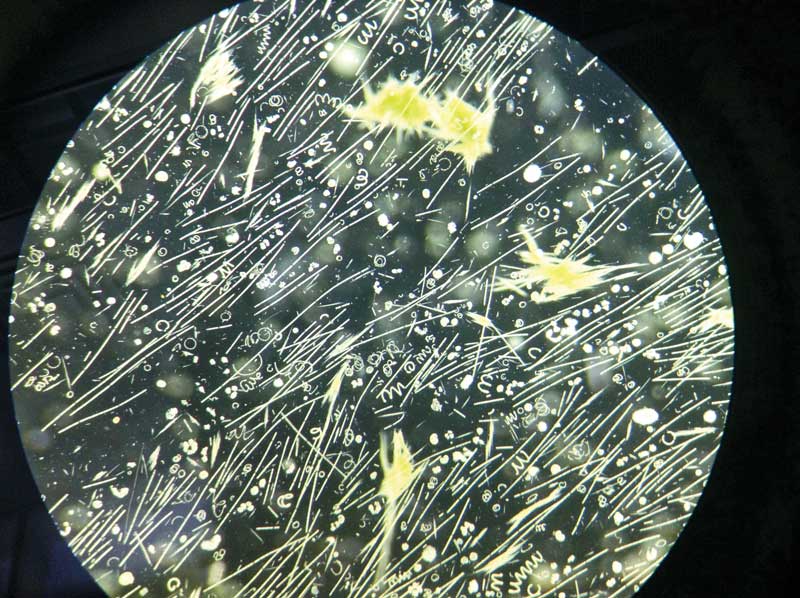

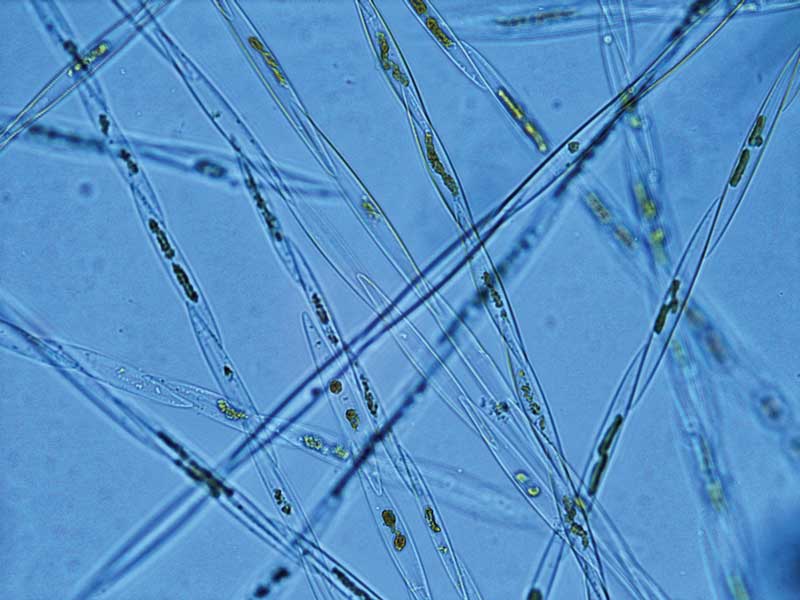

Pseudo-nitzschia microscope image from a sample taken off downeast Maine in the fall of 2016. Photo by Peter Countway

Pseudo-nitzschia microscope image from a sample taken off downeast Maine in the fall of 2016. Photo by Peter Countway

Pseudo-nitzschia: Our first story begins in San Francisco. A trolley passes by, and a woman crosses the street, emerging from the urban bustle. Her morning walk is suddenly interrupted by a catcall, and then by an unsettling cacophony of birds overhead.

This is the foreboding opening sequence to Alfred Hitchcock’s horror-thriller feature The Birds. Throughout the film (spoiler alert), flocks of birds bombard coastal residents in bizarre and seemingly senseless ways. While this film is a well-known classic, it is often forgotten that the story was inspired by actual events. On August 18, 1961, flocks of sooty shearwaters—usually docile seabirds—dive bombed buildings in North Monterey Bay, coughed up anchovies, and died in the streets.

The phenomenon went unexplained for about 50 years, until a group of oceanographers revisited a collection of zooplankton sampled at the time of the event. The researchers were able to identify the culprits in the stomachs of the zooplankton—a tiny, single-celled algae called Pseudo-nitzschia.

Peter Countway collects a phytoplankton sample in coastal Maine waters. Photo by Sara WoodmanPseudo-nitzschia is a diatom—a glass-walled algae—that can produce a toxin called domoic acid. Not all Pseudo-nitzschia are toxic. But when certain conditions are just right in the ocean, and the bloom starts to churn out domoic acid, the results can be deadly. Domoic acid is a neurotoxin that accumulates in the food chain. Shellfish filter and concentrate the toxin, and birds and mammals that eat these shellfish can acquire amnesic shellfish poisoning. Symptoms include vomiting, dizziness, respiratory problems, seizures, and possibly death. This was the sad fate of the shearwaters that day in 1961.

Peter Countway collects a phytoplankton sample in coastal Maine waters. Photo by Sara WoodmanPseudo-nitzschia is a diatom—a glass-walled algae—that can produce a toxin called domoic acid. Not all Pseudo-nitzschia are toxic. But when certain conditions are just right in the ocean, and the bloom starts to churn out domoic acid, the results can be deadly. Domoic acid is a neurotoxin that accumulates in the food chain. Shellfish filter and concentrate the toxin, and birds and mammals that eat these shellfish can acquire amnesic shellfish poisoning. Symptoms include vomiting, dizziness, respiratory problems, seizures, and possibly death. This was the sad fate of the shearwaters that day in 1961.

Most toxic Pseudo-nitzschia blooms in the United States have been on the west coast. In the fall of 2016, however, a toxic bloom occurred along the downeast coast of Maine. It appears to have been a Pseudo-nitzschia species new to Maine. Some species may be spreading their ranges due to both climate change and transport in bilge water. Luckily for seafood fans, shellfish in Maine are rigorously tested.

Still, more blooms mean more closures and more economic losses—not to mention the insane birds.

Dinoflagellates: Our second story takes us back a little further, to Mexico in 1648. A Franciscan monk named Fray Diego Lopez de Collogudo wrote of a ship from Spain that “encountered a mountain of dead fish near the coast.” Based on his account, this was likely an early report of a fish kill caused by a toxic algae called Karenia brevis.

Karenia is a dinoflagellate—another single-celled algae. This one swims around by wiggling tiny hairlike appendages called flagella. It is common in the Gulf of Mexico, and when large blooms occur, the production of brevitoxin can cause paralysis and death in fish, birds, and mammals. It can even cause coughs and wheezing in beachgoers who inhale the air near a red tide. As with Pseudo-nitzschia, there is careful monitoring in place.

Dinoflagellates are found all around the world. Many produce the bioluminescence that makes waves sparkle at night. Some are responsible for the type of algal blooms that gave red tides their name, though they come in a range of colors including pink, orange, brown, and green. They are a natural part of marine ecosystems, and many of them have a yearly bloom cycle, much like plants on land.

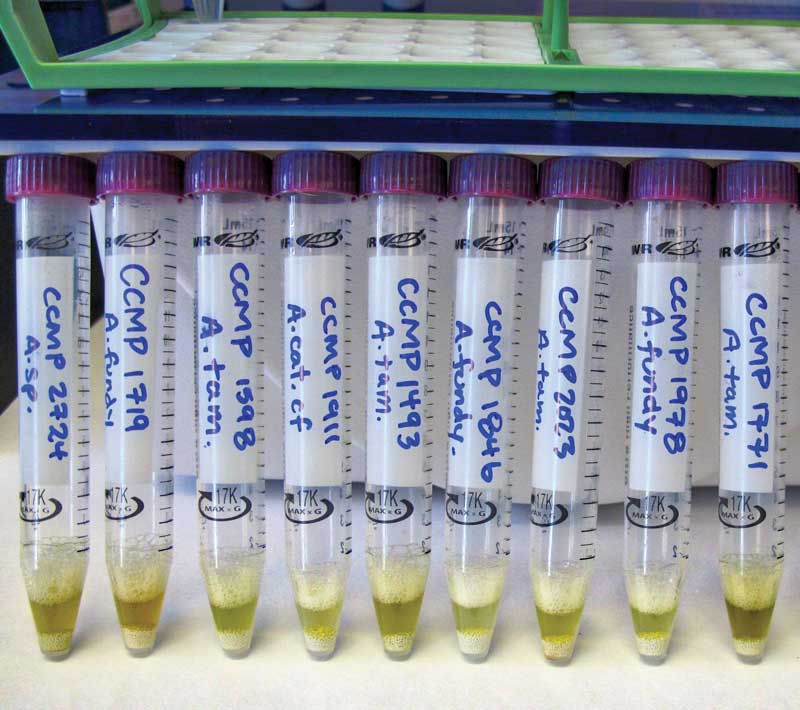

Samples of Alexandrium from Bigelow Laboratory’s collection. The collection was named a National Center and Facility by the U.S. Congress (Public Law 102-587, Oceans Act of 1992), and this collection of strains enables the study of harmful algal blooms. Photo by Peter Countway

Samples of Alexandrium from Bigelow Laboratory’s collection. The collection was named a National Center and Facility by the U.S. Congress (Public Law 102-587, Oceans Act of 1992), and this collection of strains enables the study of harmful algal blooms. Photo by Peter Countway

In the Gulf of Maine, the most commonly referred to “red tide” is another dinoflagellate called Alexandrium. It doesn’t actually turn the sea red, but it’s still a concern for shellfish growers and harvesters. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association produces red tide forecasts—much like weather forecasts—so that people can stay on top of the blooms.

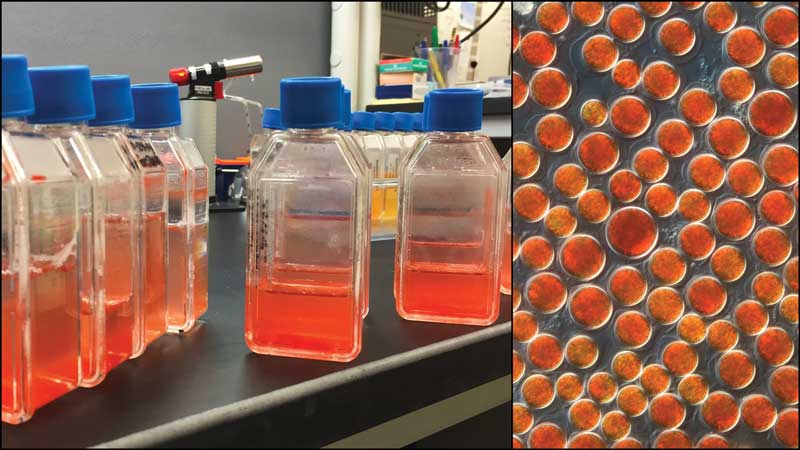

Not all colorful blooms are harmful or toxic. This species, Haematococcus, produces a bright red pigment, and has potential use in fish feed. Photo by Peter Countway

Not all colorful blooms are harmful or toxic. This species, Haematococcus, produces a bright red pigment, and has potential use in fish feed. Photo by Peter Countway

Cyanobacteria: The last tale starts roughly 2.45 billion years ago. There was no San Francisco or Gulf of Maine, but there was a microbe-filled ocean. If you could travel back in time to look around, as soon as you stepped out of your time machine into the open air, you would quickly suffocate. At that time, there was no oxygen in Earth’s atmosphere.

The reason we have breathable air on Earth is because a group of organisms called cyanobacteria spread across the oceans, leading to photosynthesis on a massive scale. Cyanobacteria, though they used to be called “blue-green algae,” are a type of bacteria. One of the outputs of photosynthesis is breathable oxygen, which filled the atmosphere over the ensuing hundreds of millions of years.

So—thank you, cyanobacteria.

The downside to cyanobacteria, as you might have guessed by now, is that some of them produce harmful blooms. Fast-forward a couple of billion years to the present day, and human civilization has clustered around water reservoirs across the globe. Urban populations draw on these reservoirs for drinking water. At the same time, large-scale agriculture around reservoirs sends excess nutrients flowing into them. When nutrients are high and weather conditions are right, toxic cyanobacteria blooms can occur, making water unsafe to drink.

A microscopic close-up of an Alexandrium cell, which is what many people think of as red tide. Photo courtesy National Center for Marine Algae and Microbiota, Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean SciencesThe toxin is called microcystin, and produces symptoms like rashes and liver damage. In 2014, a toxic bloom shut down the drinking supply for 500,000 people in Toledo, Ohio, and led the governor to declare a state of emergency. Due to land development and climate change, toxic cyanobacteria blooms are becoming more common, and even occur in Maine.

A microscopic close-up of an Alexandrium cell, which is what many people think of as red tide. Photo courtesy National Center for Marine Algae and Microbiota, Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean SciencesThe toxin is called microcystin, and produces symptoms like rashes and liver damage. In 2014, a toxic bloom shut down the drinking supply for 500,000 people in Toledo, Ohio, and led the governor to declare a state of emergency. Due to land development and climate change, toxic cyanobacteria blooms are becoming more common, and even occur in Maine.

There are myriads of microbes in the world’s oceans and lakes. One drop of seawater can contain millions and millions of them. Some are harmful algae, others are quite beneficial to humans. We might not think about microscopic life forms on a daily basis, but they are fundamental players in our health, our safety, and our economies. As funding for Earth science comes under threat, we should keep in mind that we ignore the Earth’s microbiome at our own peril. When the color of the sea tells a story, we would do well to pay attention.

Dr. Nicholas R. Record is a senior research scientist at Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences. Disclosure: The author shares a distant ancestor with modern-day algae.

State toxin monitoring

A toxic bloom of Pseudo-nitzschia last fall prompted the recall of more than 58,000 pounds of blue mussels from shellfish dealers and led to the closure of hundreds of miles of Maine coastline to shellfish harvesting for more than two months.

A similar Pseudo-nitzschia bloom in 2016 also forced a recall and closed a large stretch of coastline to harvesting. No illnesses were reported as a result of either bloom.

Hoping to prevent yet another recall, the state is re-evaluating its shellfish monitoring program to be more proactive by closing harvesting areas earlier, according to Maine Department of Marine Resources spokesman Jeff Nichols.

Until now, Maine’s biotoxin monitoring program has been focused on Alexandrium (what most of us think of as red tide.) Its blooms are fairly gradual. Pseudo-nitzschia blooms at a much faster rate and can become poisonous quite suddenly. Researchers are still trying to figure out why.

In order to make sure there are no known alerts in place, people who want to harvest shellfish for personal consumption should always check with their local municipality.

“There may be a requirement for a license for recreational harvesting and towns receive notices on closures,” Nichols said.

DMR also posts notices of closures HERE