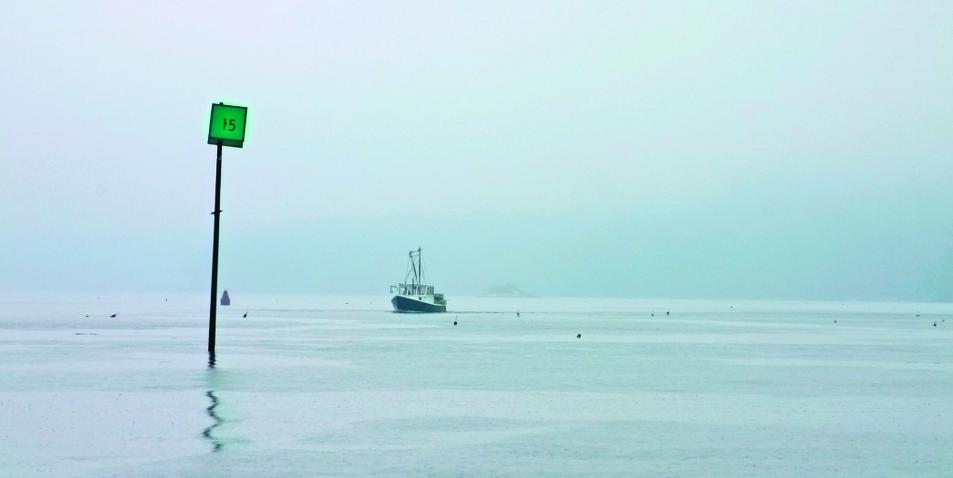

Boat and Spindle

Boat and Spindle

Photographs by Al Trescot

My general use of the word “river” when speaking of the Damariscotta should not limit the reader’s interpretation and imagination to thinking that by that term I’m referring merely to the wide ribbon of water that courses past. For me, this river is rather a super-organism, in the same sense as the school that sees planet Earth—the sum of all its parts, plant, animal, and mineral, and the stabilizing interaction of all its natural systems—as one, large planetary organism.

“While there are distinct locations or even whole stretches along the river, they are like the rooms in a house—serving different functions and playing different roles in the lives within, but as a whole, they become a home.” -Saltwater Farm, South Bristol

“While there are distinct locations or even whole stretches along the river, they are like the rooms in a house—serving different functions and playing different roles in the lives within, but as a whole, they become a home.” -Saltwater Farm, South Bristol

Similarly, a “river,” by rights, breaches the bookish definition by encompassing all that it influences, by throbbing with the pulse of its whole, by having its character manifested in the sum of its myriad biota, geologic structure, water flow, chemistry, seasons, and moods. It is a living, breathing organism unto itself.

But I’m playing with definitions. I wade through this only to emphasize that this river place, once entered, is a whole and separate world, self-sustaining and all-encompassing, to include me and my way of life.

And I’m not alone. There’s the bald eagle, sometimes with its mate, who regularly visits this point of ours. I look up and am suddenly aware of its huge, dark shape sitting in a big, old pine on the shore—still and silent and very much THERE.

The Tug Louise BAnd the eagle is not alone, for presently a crow shows up, abruptly landing and swaying on a dead branch. It, too, is silent . . . for a few moments at least . . . until it starts calling for the rest of its gang. Whereupon, their raucous and muscular assault on the intruder transforms our dignified eagle into a harried fugitive. After launching itself with a slow-falling, cascade of broken branches, it flaps determinedly for clear air space, veering sharply with every whooshing strafe by the crows. The crows hound the great bird relentlessly to the far shore and then leave off, satisfied they’ve rid the neighborhood of this riff-raff.

The Tug Louise BAnd the eagle is not alone, for presently a crow shows up, abruptly landing and swaying on a dead branch. It, too, is silent . . . for a few moments at least . . . until it starts calling for the rest of its gang. Whereupon, their raucous and muscular assault on the intruder transforms our dignified eagle into a harried fugitive. After launching itself with a slow-falling, cascade of broken branches, it flaps determinedly for clear air space, veering sharply with every whooshing strafe by the crows. The crows hound the great bird relentlessly to the far shore and then leave off, satisfied they’ve rid the neighborhood of this riff-raff. Oyster Farm with Damariscotta Village in the DistanceCrows are like that. One clear October afternoon, I was working on my roof and caught some motion out of the corner of my eye, down on the shore. The tide was out. Then I saw a low, dark shape scurrying among the rocks, checking out tide pools, poking into cracks, disappearing and reappearing in a methodical search for . . . what I wasn’t sure—crabs maybe, or small eels. It was a mink. Pretty soon, unexpectedly, it surmounted a ledge and ran dead into a group of foraging crows, who, I don’t have to tell you, got themselves pretty worked up over this intruder. They flapped themselves into a total frenzy, harassing the poor creature so thoroughly that it somersaulted repeatedly under their attacks to avoid being bonked on the head by a shiny, black beak. Crows think they own the place.

Oyster Farm with Damariscotta Village in the DistanceCrows are like that. One clear October afternoon, I was working on my roof and caught some motion out of the corner of my eye, down on the shore. The tide was out. Then I saw a low, dark shape scurrying among the rocks, checking out tide pools, poking into cracks, disappearing and reappearing in a methodical search for . . . what I wasn’t sure—crabs maybe, or small eels. It was a mink. Pretty soon, unexpectedly, it surmounted a ledge and ran dead into a group of foraging crows, who, I don’t have to tell you, got themselves pretty worked up over this intruder. They flapped themselves into a total frenzy, harassing the poor creature so thoroughly that it somersaulted repeatedly under their attacks to avoid being bonked on the head by a shiny, black beak. Crows think they own the place.

Mile by mile, the river is very much a collection of interacting communities of many different species. “Neighborhoods” is how I think of them, and they are made up of individuals with distinct personalities. Ospreys are a good example. When I used to work at the University of Maine’s Darling Research Center, I commuted by dory from my home near Merry Island on the Edgecomb shore. The green day beacon just south of the island has for years been the nest platform for one or another family of ospreys. I say “one or another” because on my daily comings and goings, I observed very different behaviors from year to year in the parent birds, suggesting they were not the same individuals each season.

One year in particular, those ospreys made it their policy to not let a single cormorant wing downriver past their nest unmolested (at least not when I was watching). Time after time, I was witness to what must have been a highly traumatizing experience for the clueless cormorant who dared to barrel on down the pike too closely. One (or sometimes both) of the adult ospreys would launch off its perch, either in a nearby tree or on the nest, and hurtle in the most menacing fashion after the cormorant, who, at the very last instant before being overtaken, would ditch into the water. Upon resurfacing and looking nervously about, it desperately tried to get airborne once more, whereupon the osprey(s) dove on it again . . . and again . . . and again. I never saw a cormorant injured in these attacks, but this regular performance went on for weeks. The next year? Nothing of the kind.

Sunset on a Frozen River

Sunset on a Frozen River

Such bullying by ospreys has taken a new turn recently where I now live, in Walpole. This time the regular victim is a great blue heron. Both birds are local to the neighborhood. I’ll hear the most dreadful squawks coming from the cove by our island and, looking up from my weeding in the vegetable garden, spy the osprey repeatedly power-diving at a heron standing on the shore. With each dive, the heron ducks its head and clambers out of the way in the most inelegant manner. Finally, in desperation, the heron takes off in that slow, lumbering fashion that they do, only to be beset upon again by the osprey in what has the sound and appearance of being a pretty nasty business. Like the cormorants of years past, the heron has no choice but to ditch. With those long legs and no webbed feet, this makes for a sad spectacle, the whole time the cove echoing with the heron’s frantic calls. And of course my thoughts have to do with whether or not the heron will be able to lift its soggy self out of the drink. It does, clumsily, many times, only to be driven back down, over and over. Eventually, though, the osprey relents, and the poor heron labors off upriver like some battle-worn B-29 retreating from hell. The only thing that seems to be at issue in these instances is territorialism. There is no food-robbing taking place. The trespassers appear simply to be getting on the ospreys’ nerves.

Catching the Tide

Catching the Tide

Osprey nests seem to show a good deal of quirky variation as well. Typically, ospreys choose tall trees, navigational markers, and elevated structures near the water for nesting sites. But I have seen nests built on house chimneys, boat docks, and even right on the rocky shore, where one might walk right up to them. And although the nests themselves are generally recognizable, concave platforms of dead branches, some are pathetically under-built and falling apart (probably first-year nesters), while others are masterful constructions of truly impressive dimensions, having been built up over many seasons. There is currently a nest in a big leaning pine downriver that must be six or seven feet tall. Eventually its growing weight will bring the tree down.

Ospreys are favorites among river watchers, partly because of their comeback in numbers after the scourge of DDT. But I think their presence on the river is a prime illustration of what gives the local neighborhood character. Their high-pitched raptor call, their spectacular fishing technique, their babies peering out of their nests, their watchful silhouettes perched in a dead snag, and their interaction with the rest of the river community—all these, to great effect, create the sense of place.

What is so rewarding to the observer is the rich variety in both animal and plant species in traveling the river, not to mention the varying heights of land, rock formations, shoreline and, of course, human habitations and settlements. These many neighborhoods that make up the river as a whole, while different, lend a coherence to this twelve-mile riverine community that seems both brilliant in design and, from my appreciative perspective, providential. All the elements necessary to complete the picture of a healthy and beautiful tidal river are here, each playing its niche role, each adding to the marvelous complexity of the system and making it work.

It can be a line of ledges serving as a regular haul-out for resting seals, a place likely as well to be frequented by feeding gulls and cormorants, and littered with their refuse of broken shells and the whitewash of their guano. Such a spot has mainly the character of a place used for loitering.

Osprey Nest in Lowes CoveThen, in contrast, there are many parts of the river where the low tide shore is acre upon acre of mudflats. These are very busy places where many species (including man) work the flats hard for the even greater number of species of shellfish and other invertebrates that grow there—millions of little lives teeming with activity . . . and millions of deaths both sustaining the foragers and lending their remains to the rich, black muck and heavy, clamflat aroma. When the tide comes back in, so do striped bass and other foraging fish to take advantage of the disturbed flats. Of course the gulls and others are nearly always present, but if it is the season for spawning worms, for example, or migrating shoals of tiny herring, the surface activity over the flooded bounty becomes a great free-for-all of screaming and bickering birds, and I can well imagine some pretty energized stripers swirling just beneath their feet.

Osprey Nest in Lowes CoveThen, in contrast, there are many parts of the river where the low tide shore is acre upon acre of mudflats. These are very busy places where many species (including man) work the flats hard for the even greater number of species of shellfish and other invertebrates that grow there—millions of little lives teeming with activity . . . and millions of deaths both sustaining the foragers and lending their remains to the rich, black muck and heavy, clamflat aroma. When the tide comes back in, so do striped bass and other foraging fish to take advantage of the disturbed flats. Of course the gulls and others are nearly always present, but if it is the season for spawning worms, for example, or migrating shoals of tiny herring, the surface activity over the flooded bounty becomes a great free-for-all of screaming and bickering birds, and I can well imagine some pretty energized stripers swirling just beneath their feet.

Where there are narrows and constrictions in the river, the current runs hard in boils and standing waves, surging around and over rock obstructions, scouring, mixing, flushing. The power of this tidal action is the most important force at work here in refreshing our estuarine environment and transporting planktonic organisms.

My point in all of this is that while there are distinct locations or even whole stretches along the river that each have their definable character, that stand out in my mind, they are like the rooms in a house—serving different functions and playing different roles in the lives within, but as a whole, they become a home.

I know where to go to gather oysters or mussels or to dig clams—all different places. I know where I am most likely to get a striper hit in the first few casts, a mysterious place where bubbles have for years risen up from the muddy bottom, and find an oak ridge frequented by wild turkeys and where the coyotes yip and howl in the moonlight. I know where I can glide along a steep, brooding, forested shore, or find a secluded and quiet picnic spot with good swimming, or go to find a waterfall no one else seems to know about. I know where the eagles’ nest is, downriver, and where huge hemlocks hang far out over steep ledges so a boat can ride in under them.

And then there are communities of clustered houses and anchorages, and the four villages of Damariscotta, Newcastle, South Bristol, and East Boothbay with their active harbors and close ties to the river—boatbuilding, marinas, fishing, aquaculture, light industry, restaurants, and stores.

All these elements comprise the continuum called the Damariscotta River, my home river, distinct from every other river in the world.

Barnaby Porter’s many careers include marine biologist, aquaculturist, and running a woodworking business. He has made serious stabs at the art world, been a newspaper columnist, and an essayist on Maine Public Radio.

Al Trescot is a graphic designer, photographer, and “book creator.”

Excerpted by permission from the book Twelve Miles from the Rest of the World: A Portrait of the Damariscotta River, ©2005 by Barnaby Porter and Al Trescot. Rocky Hill Publishing: