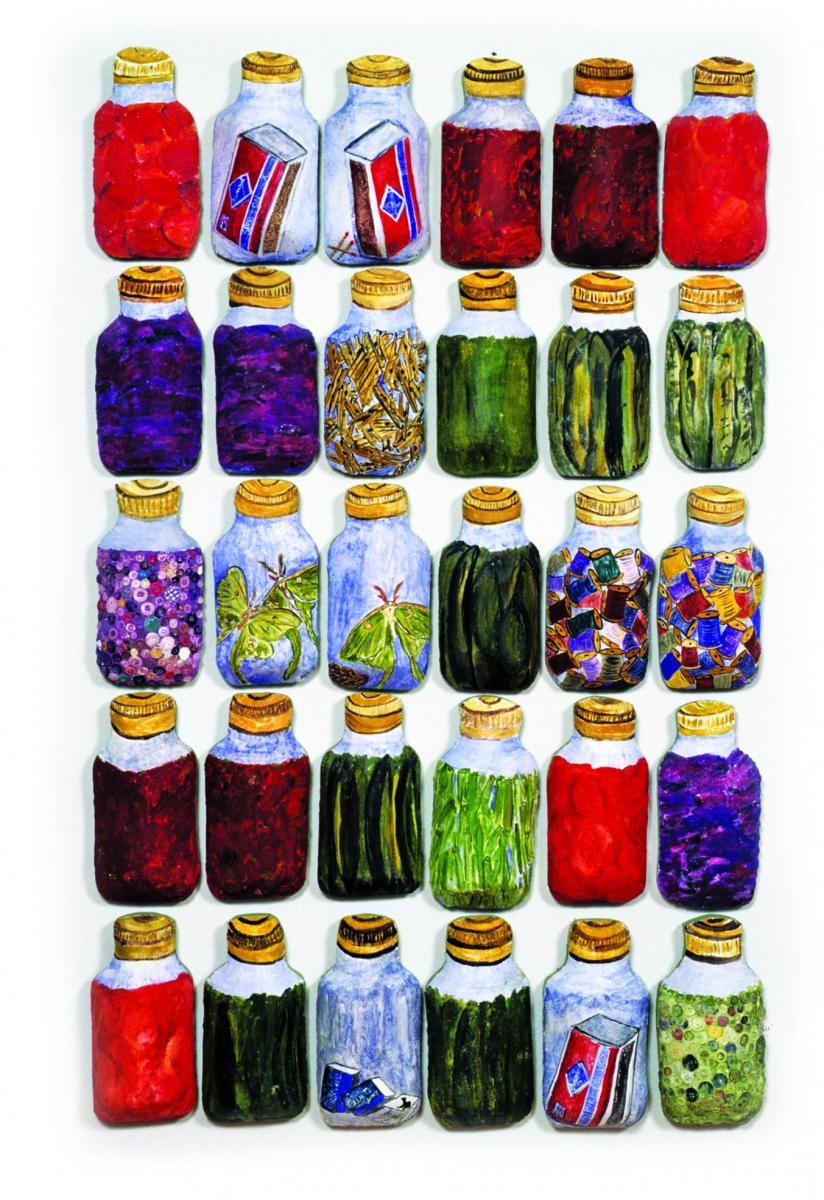

Pantry, 2006. Shaped fresco, 48" x 37" x 3". Courtesy of Caldbeck Gallery (5)

Pantry, 2006. Shaped fresco, 48" x 37" x 3". Courtesy of Caldbeck Gallery (5)

Solon is a small central Maine town, population around 1,000, that’s about a 20-minute drive north of Skowhegan. Bordered to the west by the Kennebec River, the area is rural and somewhat remote. It’s also the center of artist Barbara Sullivan’s very busy universe—her heart and, well, Solon.

When I met with her on a day in late June, Sullivan had already played tennis and was making plans to cater the fast-approaching Kneading Conference and Artisan Bread Fair in Skowhegan, where she’d be preparing meals for 250 people. She also was arranging a trip to Cushing with her friend, painter Abby Shahn, to look at work by sculptor Bernard Langlais that is being distributed to organizations around Maine through the Kohler Foundation. And she was thinking about what she would teach at the University of Maine at Farmington in the fall and about making Christmas wreaths this winter.

Then there was the next fresco piece to consider. Sullivan took up this labor-intensive mural-painting technique, which involves lathe, plaster, and extensive preparation at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in 1988 and has specialized in it ever since. While she employs the classic buon, or true, fresco method, her pieces are not your Renaissance ancestor’s murals—no holy haloed figures or winged angels here. She offers a wonderfully eclectic and engaging array of objects and figures, from a chainsaw to women having their hair done, painted with a lively hand and a wry eye for the ways in which we live our lives. Landscape Chair, 2013. Shaped fresco, 46" x 33" x 6"

Landscape Chair, 2013. Shaped fresco, 46" x 33" x 6"

Sullivan’s fresco work has earned her several prestigious awards (most recently, a Gottlieb Foundation grant in 2011). She has been juried into three Portland Museum of Art biennials and has had solo shows at the Center for Maine Contemporary Art and the University of Maine Museum of Art. This past summer she was included in the landmark “Maine Women Pioneers III” exhibition at the University of New England Art Gallery and was featured in “Significant Works” at the Caldbeck Gallery in Rockland where she has had eight one-person exhibitions since 1996.

Sullivan was born in Skowhegan in 1950, the seventh of nine children, and grew up on a farm in Fairfield. Her family had come to Maine from Boston. Her mother, Ellen, had worked in interior design and her father, George, was a physician who practiced in Bingham, Maine, for 25 years. A flight surgeon during World War II, he became chief of anesthesiology at the Seton Hospital in Waterville while maintaining a part-time general practice. When she bought land in Solon, Sullivan remembered telling her father, “This place is so familiar.” For good reason: he had taken her on house calls in the area.

The family had a large garden and animals. “You never forget that stuff as you age, and you come back to it somehow,” said Sullivan. While she enjoys visiting cities, she loves returning to Solon. “And I can’t imagine ever not having a garden,” she averred.

Sullivan was a maker from the time she was little. She was always drawing, and had a room of her own with a little closet where she created doll clothes with patterns made of Kleenex, which she would sell. Sometimes her mother helped, but she didn’t have a lot of time.

Her parents routinely opened their house to patients. “Someone would call to say ‘so and so is only two centimeters dilated,’” Sullivan related. “The family would stay with us till the mother delivered—we’d be changing beds as people would be showing up.” Looking back, Sullivan credited her parents with instilling in their children a sense of self-reliance. “They really made us do everything,” she recalled.

Sullivan’s education took a number of twists and turns after high school (Coburn Classical Institute in Waterville). She attended classes at the Concept Center for Visual Studies in Portland and did a two-year stint at Montserrat College in Beverly, Massachusetts, which offered a range of studio and theory courses. Wondering if she was ever going to “really paint” if she stayed in school, Sullivan left Montserrat and returned to Maine. She held odd jobs to make ends meet, including working at an electronics factory at night. Sullivan has taken the ancient art of fresco out of its traditionally sacred setting and into everyday life. Photo by Jay York

Sullivan has taken the ancient art of fresco out of its traditionally sacred setting and into everyday life. Photo by Jay York

Thinking she might go to graduate school, Sullivan realized she had to first earn an undergraduate degree. She calledher friend, the painter Tom Higgins, who taught at the University of Maine at Farmington. He suggested she enroll there. She ended up getting a degree in creative writing and studio art in 1996.

From Farmington, Sullivan was accepted into the Masters in Fine Arts program at Vermont College in Montpelier in 1997. There her teachers confirmed an activist streak in their student and her art. She also studied with Faith Wilding, a Paraguayan-American artist whose work focused on feminism and domesticity, both of which interested Sullivan.

After graduating, Sullivan landed a job filling in for Higgins at UMF while he was on sabbatical. She has taught there ever since, offering drawing, painting, and other classes in the art department. She also teaches fresco at Colby College and will lead a workshop at Anderson Ranch in Aspen next summer. Round Oak Installation, 2011. Sharpie on photo backdrop paper and shaped fresco, 108" x 84"

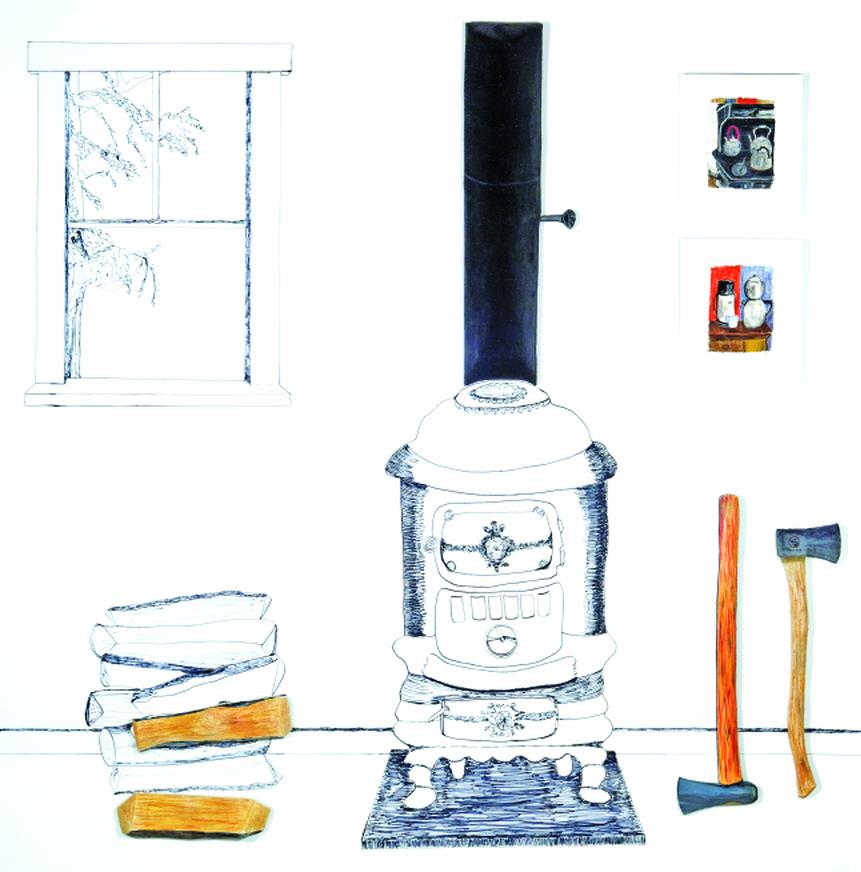

Round Oak Installation, 2011. Sharpie on photo backdrop paper and shaped fresco, 108" x 84"

Sullivan moved to Solon in part for the exceptional cross-country skiing, but the community also boasted a lively group of artists and craftspeople. She designed her home there based on memories of houses she had seen while traveling or that she had lived in or loved. Built for efficiency, the house is positioned for solar gain, with a heated slab and a small footprint. Family and friends helped her frame it.

Another major reason for the move to Solon was the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture just down the road. In 1988, Sullivan became the school’s first artist-cook. The eight or so summers she spent in that position represented “a very large part of my art education,” she said. One of the first lectures she attended was by figurative painter Joan Brown. Presentations by Claes Oldenburg and Red Grooms also left a lasting impression.

Not long after becoming cook, Sullivan was offered “a little teeny studio” at the school by then-director, Barbara Lapcek. As it turns out, the space was near the fresco barn. Skowhegan is one of only a handful of schools in the country that offer classes in the mural technique, which dates back to ancient days, and which flourished during the Renaissance. Sullivan remembered students and faculty suggesting that she would love fresco because it was so physical and because she had built her own house.

Walter O’Neill, a fresco instructor, prepared a panel for her and explained the process. She had done some plastering in the past as a mason’s tender and worked with sculpting materials, including clay, but grinding pigments and other aspects of the fresco process were new.

O’Neill gave her a bucket of slaked lime (produced in Skowhegan) and suggested she try it out over the winter. “Keep doing it and you’ll get it,” he said. That year she discovered her medium and never looked back.

One of the things Sullivan loves about fresco is how laborious it is. The setup is complicated—cutting plywood forms, building a wire-lathe armature, applying the irrichio (a plaster-like substance). It has to be done just right before the painting can take place. “I love to do things the hard way,” she said.

Once she mastered the plaster, Sullivan started making single objects that she would arrange on walls. These collections, which she called “scenarios,” hinted at narratives, but ones which the viewer was obliged to construct.

Among Sullivan’s first large pieces was one for the cafeteria in the Cross Office Building at the State House in Augusta in 1999. The theme was Maine food products: blueberries, lobsters, sardines, apples, potatoes—78 individual pieces in all. “It took me about a year and a half to do the research and complete it,” she said.

Over the years Sullivan has tended to work thematically. For a 2001 show at the Caldbeck Gallery she produced a one-room efficiency apartment. The piece included a frieze that circled the top of the room, an element that underscores her interest in architectural components. At the Center for Maine Contemporary Art in 2003 Sullivan presented “Inside the Bedroom,” in which even the curtains were fresco. A year later, she created a beauty salon in the Clark House Gallery in Bangor. Thanks to a Good Idea Grant from the Maine Arts Commission, the installation included sound: visitors would trip a switch to hear a short recording of “hair conversations.”

Sullivan has always infused her work with a sense of humor, although it took her a while to come around to the notion that her art could be both meaningful and amusing. After the start of the first Gulf War in 1990, she attended peace meetings. She decided to paint Solon friends and neighbors and ended up with 52. If someone didn’t show up for a sitting, Sullivan would paint herself. When she showed slides of these self-portraits to fellow artists at Skowhegan, they laughed. “I didn’t think they were that funny,” Sullivan recalled, but the response was a revelation.

Among her self-portraits is a series showing her with birds on her head, a riff on fashionable vintage millinery. Sullivan has also portrayed herself putting on make-up, Q-tipping her ear and other activities that “other people don’t see you do.”

Debbie and Her Stove, 1999. Shaped fresco, 108" x 72"

Debbie and Her Stove, 1999. Shaped fresco, 108" x 72"

Sullivan’s series depicting women involved in domestic activities had great success at the Morgan Rank Gallery in Easthampton, New York, in the late 1990s. She had been leading a fresco workshop at the Art Barge in Amagansett when Rank asked about her work. She sent him postcards from previous shows. When she didn’t hear back, she sent him a fresco telephone with a note that read, “Call me.” He thought it was hilarious and asked for as much work as she could send.

Sullivan’s Solon studio is as spacious as her home is cozy. Originally a garage, the open space is filled with frescoes. The walls offer an assortment of new and old pieces: birds, an armchair and settee, a cleaver, a can of Maxwell House coffee, a couple of steaks—even a stack of bikini underwear. A small panel on a table shows a view of the fireplace in the main hall of Fairfield Porter’s house on Great Spruce Head Island where Sullivan spent a week as part of an annual artists’ retreat.

When Sullivan moved into the space in 1997, her work became larger and then life-size. She began to think beyond individual pieces and branched out into creating installations.

Recently, she has been doing large drawings as backdrops to her fresco pieces. Inspired by stories of Matisse lying in bed drawing with chalk on the ceiling using a long stick, she has repurposed thin pieces of wood to which she attaches black Sharpies. She also works up close from a ladder.

In the summer of 2012 Sullivan created “Nature & Man/Friends & Foes,” an installation at the Turtle Gallery in Deer Isle that featured a 24-foot-long drawing accented with various fresco pieces: a wicker chair, a swimmer, birds, a skunk. For another recent project, “Painters, Players and Poets,” a collaboration featuring 48 Maine artists, Sullivan teamed up with poet and Colby College English professor Peter Harris. Harris wrote a poem about one of Sullivan’s pieces and she made a fresco inspired by a poem he had written about his daughter, who took care of Alzheimer’s patients. “Painters, Players and Poets” traveled for a year around Maine and up to St. John, New Brunswick.

Sullivan has lived a second life as a chef and caterer. “I’ve just always been interested in food,” she noted, adding that her mother was “a kind of a Julia Child nut” and her father a very good cook.

Q-Tip Self Portrait (detail), 1992. Oil on canvas, 17" x 24"

Q-Tip Self Portrait (detail), 1992. Oil on canvas, 17" x 24"Her stint as cook at the Skowhegan School provided the experience for cooking for large groups. The first year she was involved with the Kneading Conference, she made a Maine farm dinner for the presenters the night before the event started. She also was recruited to house some of the special guests. She has had memorable visits with such notable food authorities as Nancy Harmon Jenkins, Naomi Dugid, and Edward Behr.

Since the first Kneading Conference in 2010, Sullivan has witnessed Skowhegan move from “dormancy to vibrancy.” The city has become a model for a food-based economy in Maine, largely because of the new Somerset Grist Mill. Sullivan serves on the Maine Grain Alliance board and is excited about the resurgence in grain farming in Somerset County.

Nowadays, Sullivan is enjoying being a grandmother. Her daughter Gabriel, a speech pathologist in Boston, has a two-year-old daughter, Isabella. Sullivan also travels, often to see art.

Back at home, Sullivan keeps an eye on the South Solon Meeting House just down the road from her home. She serves on the organization’s board and from time to time leads a tour of the historic structure. She is the perfect person to do it: the meeting house’s interior is decorated with frescoes painted by a group of painters from the early days of the Skowhegan School, including Ashley Bryan, Anne Poor, and Willard Cummings. Needless to say, Sullivan feels right at home.

Carl Little’s latest book is Nature & Culture: The Art of Joel Babb (University Press of New England). He lives and writes on Mount Desert Island.

Barbara Sullivan is represented by the Caldbeck Gallery in Rockland (www.caldbeck.com).

She will have a solo show there during the 2014 summer season titled “The Showroom, A Furniture Store.”