The collection of low buildings juts anonymously into Rockland harbor between the Coast Guard station and the Maine State Ferry Service landing. There is little signage or visible activity to hint at what goes on inside. The under-the-radar nature of this facility—currently owned and operated by a subdivision of the FMC Corporation—is like the seaweed industry as a whole. While seaweed today is touted as a new health food, fertilizer, and energy source, its historic role in America’s food industry seems largely unknown.

The FMC Health and Nutrition plant in Rockland, Maine. Photograph by Josie IselinOver the years in this Rockland factory, a group of chemical engineers, known by some as “the pudding boys,” have experimented with seaweed derivatives to help develop the processed food experience we take for granted today. Their work promoting carrageenan as a versatile texturizer became essential to the burgeoning corporations of the post-war boom, ever expanding the variety of ready-made foods. It is hard to know which drove which: the demand for smooth, premixed products, or the thousands of samples of emulsifiers and gelling agents sent from Rockland to test kitchens at companies like Sara Lee, Betty Crocker, Kraft, Unilever and other food giants of the day that were developing and profiting from the American penchant for processed foods. FMC does not identify specific customers, but cake mixes, pie fillings, toothpaste, diet shakes, pet food, hand lotions, ice cream, mayonnaise, salad dressing—the list goes on—all use carrageenan, which was originally produced from the seaweed Chondrus cripsus, commonly known as Irish moss. For many years that moss was collected along the rocky coastline near Rockland, around the harbor of Scituate, Massachusetts (once the mossing capitol of New England), and from the Maritime Provinces of Canada.

The FMC Health and Nutrition plant in Rockland, Maine. Photograph by Josie IselinOver the years in this Rockland factory, a group of chemical engineers, known by some as “the pudding boys,” have experimented with seaweed derivatives to help develop the processed food experience we take for granted today. Their work promoting carrageenan as a versatile texturizer became essential to the burgeoning corporations of the post-war boom, ever expanding the variety of ready-made foods. It is hard to know which drove which: the demand for smooth, premixed products, or the thousands of samples of emulsifiers and gelling agents sent from Rockland to test kitchens at companies like Sara Lee, Betty Crocker, Kraft, Unilever and other food giants of the day that were developing and profiting from the American penchant for processed foods. FMC does not identify specific customers, but cake mixes, pie fillings, toothpaste, diet shakes, pet food, hand lotions, ice cream, mayonnaise, salad dressing—the list goes on—all use carrageenan, which was originally produced from the seaweed Chondrus cripsus, commonly known as Irish moss. For many years that moss was collected along the rocky coastline near Rockland, around the harbor of Scituate, Massachusetts (once the mossing capitol of New England), and from the Maritime Provinces of Canada. An Irish moss dragging rig in Pictou, Nova Scotia in 1971. Photographs courtesy Parker S. Laite, Sr. (3)

An Irish moss dragging rig in Pictou, Nova Scotia in 1971. Photographs courtesy Parker S. Laite, Sr. (3)

The Rockland plant, now called FMC Health and Nutrition, was started in the 1930s by two brothers, Nick and Bart Pellicani of Warren and a French chemist Victor LaGloahac on the site of the former Rockland Lime Company on Crockett’s Point. The original factory processed local kelp into alginate. But by the 1950s, the company had shifted its focus to carrageenan, a more cost-effective food additive.

Nick Pellicani, one of the founders of the Rockland plant, inspects Irish moss that had been harvested at Orr's Island, Maine, in 1970.

Nick Pellicani, one of the founders of the Rockland plant, inspects Irish moss that had been harvested at Orr's Island, Maine, in 1970.Carrageenan got its start as a commercial product in the 1940s when a Chicago dairy company called Krim-Ko began using it to keep the cocoa from settling to the bottom of its bottled chocolate milk. The Krim-Ko engineers may have gotten the idea from the classic New England recipe for blancmange (see inset) using Irish moss. Irish moss when boiled in milk sets up nicely into a simple and delicate pudding. The recipe likely originated in County Carregheen, Ireland, and was brought to this country by immigrants.

Workers stack bales of Irish moss at a harvesting station on Prince Edward Island in 1968. The moss came in loose, was dried, compressed into bales, and then trucked to Rockland.

Workers stack bales of Irish moss at a harvesting station on Prince Edward Island in 1968. The moss came in loose, was dried, compressed into bales, and then trucked to Rockland. Parker Laite, Sr. knows his seaweed. The longtime Camden, Maine, resident left the Merchant Marine to take a job with the Rockland factory in 1960. He arrived on the scene when Chondrus crispus suppliers could barely keep up with demand. The Rockland plant continued to send a truck down to Scituate to collect bales of Chondrus raked from just below the tide line, summer after summer, by a band of rowdy boys with dories led by a Frenchman named Lucien Rousseau. But other sources had to be found. That was Laite’s job. The search took him to Peru and then Chile, where despite not speaking a word of Spanish, he forged a relationship based on seaweed that would last 40 years. Laite travelled around the world 22 times, always in search of the next seaweed species that the engineers might devolve into the next best viscofier or emulsifier for the next best food product.  Harvesters take a break at a sea moss buying station in West Point, Maine, in 1971. In the background, their dinghies are loaded with seaweed. Photograph courtesy Parker S. Laite, Sr.

Harvesters take a break at a sea moss buying station in West Point, Maine, in 1971. In the background, their dinghies are loaded with seaweed. Photograph courtesy Parker S. Laite, Sr.

Working with botanists and engineers, experimenting with growth rates and farming locations, Laite and his colleagues hopped from one Pacific island to the next and finally landed in the Philippines, which became a primary source of farmed red seaweed.

Between 1960 and 1977, the Rockland company, then known as Marine Colloids, supplied the additives used to thicken diet shakes, make artificial syrup as thick as real maple syrup, keep cake mixes fresh and pie fillings thick, as well as, of course, keeping chocolate milk chocolate-y and toothpaste from falling apart. In 1977 Marine Colloids was bought by FMC (Farm Machinery Corporation) and renamed FMC BioPolymer. Recently the division was renamed again to FMC Health and Nutrition. Pharmaceutical uses of carrageenan to make tablets and capsules expanded markets, as did the use of the product in shampoos, conditioners, and skin lotions.

Parker Laite holds up bunches of red seaweed at a coastal location in Peru in 1968. By the late 1960s and 1970s, seaweed buyers for the Rockland plant were looking overseas for new sources and new types of seaweed. Photograph courtesy Parker S. Laite, Sr.The cover of a recent brochure outlining FMC Health and Nutrition’s vision for the future superimposes pictures of a chocolate cake and pharmaceutical tablets over an image of the rocky Maine coastline. In reality, the many thousand of tons of seaweed processed in the Rockland factory these days comes from Tanzania, the Philippines, Chile, China, and other far-flung sources. Today, the anonymous-looking Rockland factory remains the only carrageenan processing plant in the United States.

Parker Laite holds up bunches of red seaweed at a coastal location in Peru in 1968. By the late 1960s and 1970s, seaweed buyers for the Rockland plant were looking overseas for new sources and new types of seaweed. Photograph courtesy Parker S. Laite, Sr.The cover of a recent brochure outlining FMC Health and Nutrition’s vision for the future superimposes pictures of a chocolate cake and pharmaceutical tablets over an image of the rocky Maine coastline. In reality, the many thousand of tons of seaweed processed in the Rockland factory these days comes from Tanzania, the Philippines, Chile, China, and other far-flung sources. Today, the anonymous-looking Rockland factory remains the only carrageenan processing plant in the United States.

So the next time you brush your teeth and the toothpaste actually stays on your brush, think of Rockland and thank that carrageenan.

Irish Moss (Chondrus crispus)

While some beachcombers turn up their noses at a slimy piece of seaweed on the beach, they should not. Irish moss, when boiled in milk, sets up into the frothy New England fanciness known as blancmange. (See recipe.) What keeps seaweed flexible and slippery is also what keeps ice cream smooth in our mouths, lipstick smooth on our lips, and shaving cream smooth across our cheeks.

Three gelling or emulsifying agents come from seaweed: alginate, carrageenan, and agar. Alginate comes from the alginic acid in the cell walls of kelps and other brown seaweeds. Carrageenan is a cell-wall phycocolloid found in a few specific species of red seaweed, especially Chondrus cripsus (Irish moss). Agar (and agarose, a more highly refined agar) are produced from a variety of red seaweeds and are best known as the inert, gelatinous growing medium filling the petri dishes and DNA-sequencing rigs of university, hospital, and biological research labs.

Photographs and text by Josie Iselin as adapted from An Ocean Garden: The Secret Life of Seaweed

Josie Iselin is a photographer, writer, and book designer with seven books to her  credit, including the newly released An Ocean Garden: the Secret Life of Seaweed, (Abrams: March 2014). Iselin lives and works in San Francisco, and spends her summers on Vinalhaven, Maine. Her art can be found at www.josieiselin.com.

credit, including the newly released An Ocean Garden: the Secret Life of Seaweed, (Abrams: March 2014). Iselin lives and works in San Francisco, and spends her summers on Vinalhaven, Maine. Her art can be found at www.josieiselin.com.

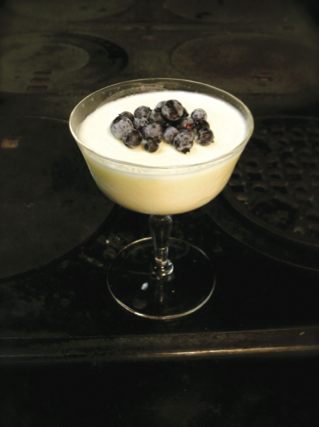

Irish sea moss pudding (blancmange)

Text and photos by David Hopkins

BlancmangeMaking blancmange (pronounced bluh-monge with the emphasis on the second syllable) from Irish sea moss is a long-time tradition along the Maine coast and on the island of North Haven where I grew up. My mother, June Hopkins, used to make it for us when I was a child, using moss we collected on island beaches. I used to package the seaweed and sell it in little bags at her gift shop with the recipe hand-printed on the outside. The price was 10 cents a bag. June says she got the recipe from someone on the island, but cannot remember whom. She is 90 now and still runs the North Haven Gift Shop, which she started 60 years ago.

BlancmangeMaking blancmange (pronounced bluh-monge with the emphasis on the second syllable) from Irish sea moss is a long-time tradition along the Maine coast and on the island of North Haven where I grew up. My mother, June Hopkins, used to make it for us when I was a child, using moss we collected on island beaches. I used to package the seaweed and sell it in little bags at her gift shop with the recipe hand-printed on the outside. The price was 10 cents a bag. June says she got the recipe from someone on the island, but cannot remember whom. She is 90 now and still runs the North Haven Gift Shop, which she started 60 years ago.

Here’s how to make it

Put in top of a double boiler:

3 cups milk

1/2 cup sugar

1 small handful of dried Irish sea moss

Cook over boiling water for 35 to 45 minutes, until the milk has thickened. Remove from heat. Strain mixture and add 2 teaspoons of vanilla. Pour into custard cups or dishes. Chill for at least an hour in the refrigerator. Add fresh berries on top, or serve plain.

David Hopkins runs the Hopkins Wharf Gallery on the island of North Haven where he grew up.