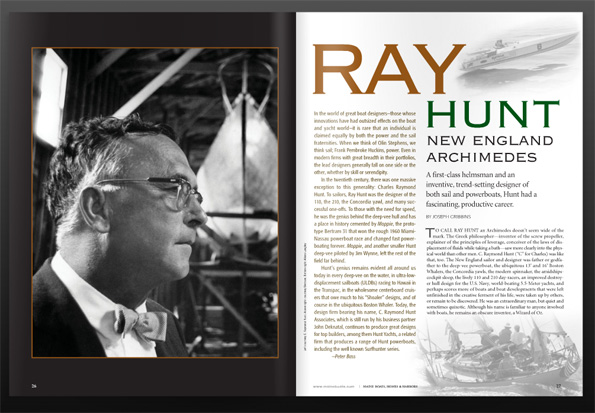

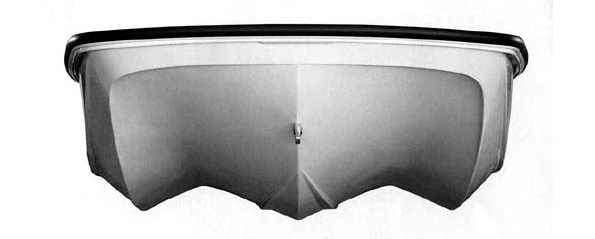

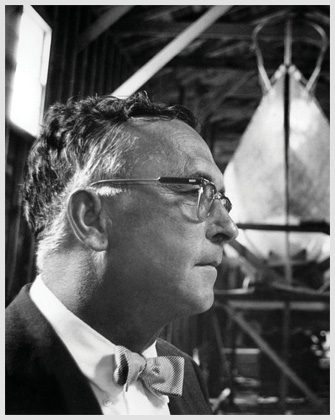

Ray Hunt, a first-class helmsman and an inventive,

trend-setting designer of both sail and powerboats.

Photo courtesy C. Raymond Hunt.

In the world of great boat designers—those whose innovations have had outsized effects on the boat world—it is rare that an individual is claimed equally by both the power and the sail fraternities. When we think of Olin Stephens, we think sail; Frank Pembroke Huckins, power. Even in modern firms with great breadth in their portfolios, the lead designers generally fall on one side or the other, whether by skill or serendipity.

In the twentieth century, there was one massive exception to this generality: Charles Raymond Hunt. To sailors, Ray Hunt was the designer of the 110, the 210, the Concordia yawl, and many suc- cessful one-offs. To those with the need for speed, he was the genius behind the deep-vee hull and has a place in history cemented by Moppie, the proto- type Bertram 31 that won the rough 1960 Miami- Nassau powerboat race and changed fast power- boating forever. Moppie, and another smaller Hunt deep-vee piloted by Jim Wynne, left the rest of the field far behind.

Hunt’s genius remains evident all around us today in every deep-vee on the water, in ultra-low- displacement sailboats (ULDBs) racing to Hawaii in the Transpac, in the wholesome centerboard cruis- ers that owe much to his “Shoaler” designs, and of course in the ubiquitous Boston Whaler. Today, the design firm bearing his name, C. Raymond Hunt Associates, which is still run by his business partner John Deknatal, continues to produce great designs for top builders, among them Hunt Yachts, a related firm that produces a range of Hunt powerboats, including the well known Surfhunter series.

—Peter Bass

TO CALL RAY HUNT an Archimedes doesn’t seem wide of the mark. The Greek philosopher—inventor of the screw propeller, explainer of the principles of leverage, conceiver of the laws of displacement of fluids while taking a bath—saw more clearly into the physical world than other men. C. Raymond Hunt (“C” for Charles) was like that, too. The New England sailor and designer was father or godfather to the deep-vee powerboat, the ubiquitous 13' and 16' Boston Whalers, the Concordia yawls, the modern spinnaker, the amidships cockpit sloop, the lively 110 and 210 day-racers, an improved destroyer hull design for the U.S. Navy, world-beating 5.5-Meter yachts, and perhaps scores more of boats and boat developments that were left unfinished in the creative ferment of his life, were taken up by others, or remain to be discovered. He was an extraordinary man, but quiet and sometimes quixotic. Although his name is familiar to anyone involved with boats, he remains an obscure inventor, a Wizard of Oz.

Ray Hunt sailed little boats in Duxbury on the South Shore of Massachusetts as a boy. His grandfather, Cassius Hunt, was a Duxbury native who had built the original Duxbury Yacht Club building on his summer property. They were a sailing family, and a sailing business family whose fish dealership, Cassius Hunt & Co. of Boston, founded in 1877, supported two generations of Hunts.

Duxbury Harbor is a shallow bight of Plymouth Bay alive with tidal currents and open to the south, a good place to feel the interaction of wind, water, and boat. It all started in that little harbor during the First World War. “Growing up in Duxbury, in those conditions of tide and current and fluky winds, he got the feel of centerboard boats; it gave him a very close touch with the water,” said Waldo Howland, patriarch of the Concordia Company and Ray Hunt’s business

partner during the 1930s.

Hunt’s “very close touch with the water,” and many other things, became apparent in the 1920s when he began sailing in the rarefied air of the Eastern Yacht Club of Marblehead. He led his Duxbury Y.C. crew of juniors to victory in the Sears Cup competition at Eastern in 1923 and repeated the feat in 1925. He was 15 when he won what has now become the Junior Sailing Championship of the U.S. for the first time, and he began to be sought out as a crewmember and clever kid by leading figures in the Massachusetts Bay yachting establishment. He sailed R-boats and Q-boats at Marblehead. In the mid- ’twenties he bought what was thought to be an uncompetitive R-boat from the designer, Frank Paine, and proceeded to beat the new Rs, including one sailed by Paine himself, in what was then the principal arena for these 25'-waterline sloops.

Paine took an interest in this astute youngster, and in 1929 Hunt was sent down to Oyster Bay with Paine’s new 8-meter

Gypsy for the eliminations to select the Seawanhaka Cup defender. Hunt and

Gypsy were selected, but it made the committee nervous that this 21-year-old from Boston had been trouncing the best of America’s 8s with a crew of three instead of five. They made him take two extra hands aboard, and

Gypsy lost the series by a narrow margin. Hunt told Yachting magazine decades later that “we could race that boat quite satisfactorily with three, and the two added crew had no experience in 8s and never worked into our system.” When the Depression came Ray Hunt was one of many young men on the loose. He found a home, and the beginnings of a profession, in Frank Paine’s design and brokerage office on Beacon Street, Boston.

Ray Hunt’s 12-meter Easterner, beautiful but not quite competitive

enough for the America’s Cup. Photo courtesy 12 Meter Charters

Paine, Belknap & Skene was a gathering place for boat-minded Bostonians in the early 1930s, and it is unclear whether some of them worked there or just hung around talking boats. Frank Paine’s brother John kept a desk there, as did Waldo Howland’s father Llewellyn, and there were other associates and visitors attached to the place, including two youngsters interested in yacht design–Arthur Schuman and Ray Hunt. “They were all racing against one another in the Marblehead area,” Waldo Howland remembered. Howland was on the loose, too, although he had made some money selling old schooners to Frank Paine’s office and talking to Ray Hunt and Arthur Schuman,” Howland remembered, and the result of those conversations, in 1932, was a Hunt-Howland partnership in the Concordia Company.

Concordia, with offices at 50 State Street, was an enterprise “with a very wide charter,” founded by Llewellyn Howland. Among its assets was Howland Island in the South Pacific. Waldo’s father gave him all the stock, and he and Ray Hunt “shared profits and expenses” in a business that began with brokerage and moved into design, boatbuilding, and eventually the renowned Concordia yard.

The new thing in racing in the early 1930s was the frostbite dinghy, and the two Concordia Company partners hatched a B-class dinghy project. They took the first boat down to Mason’s Island, near Mystic, Connecticut, won a winter regatta with it, and sold it that day. They took a second, beamier boat to Essex, Connecticut, and won two days of racing against the likes of Cornelius Shields and Briggs Cunningham. Although they only built and sold three frostbiters that winter of 1933-34, it was an auspicious beginning for Ray Hunt, a designer whose principal credentials were his instincts, and for Waldo Howland, who began putting certain things together.

“I was the salesman, and Ray was the designer,” Howland said. “It was a matter of me selling Ray Hunt.”

They soon sold a fleet of 12' hardchine boats to a group of sailing friends on a lake in Dublin, New Hampshire, and followed in the mid-1930s with Ray Hunt designs for larger boats built by Casey, Pierce and Kilburn, and Lawley’s. And in the winter of 1938-39, Hunt designed the first of the Concordia yawls for Waldo Howland’s father Llewellyn.

Ray Hunt was interested then in design, production boatbuilding, winning races—he won the Royal Bermuda Yacht Club’s Challenge Cup in 1938 in a chartered 6 Meter—and in new materials. One of the new materials in the late 1930s was plywood. He was not much of a boatbuilder, but it was part of his instinctive method that he had to get his hands on the materials and, ultimately, had to work with a prototype of what he had sketched on paper—sometimes the back of an envelope or a paper bag.

“Ray Hunt was one helluva designer, but in a non-scientific sort of way. He usually got things right, but maybe not the first time,” said Dick Fisher, his collaborator on the Boston Whaler.

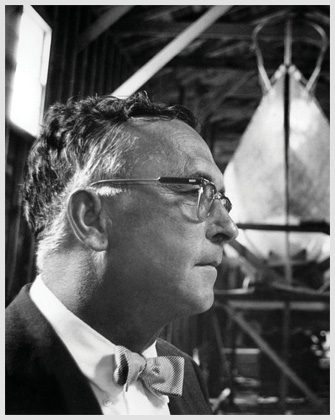

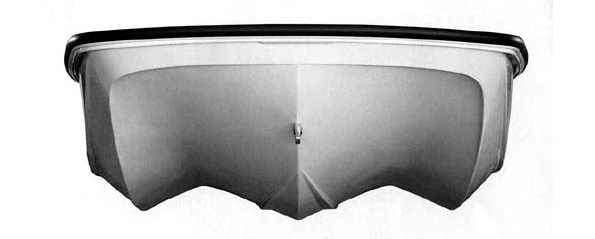

Bow-on view of the revolutionary Boston Whaler.

Dick Fisher and his partner, Bob Pierce were commissioned by Hunt to build the prototypes of what would become the 110. “Ray wanted three sailboats built that winter [1938-39]—23'x 4'—slab-sided, with a flat rockered bottom and a fin keel with a bulb, and with aircraft-wire rigging.”

Fisher and Pierce built the boats, and the project that became the 110—a high-performance sailing box of plywood that owed nothing to tradition—was later given to Lawley’s for volume production. Hunt would follow the 110 idea with the 210, the 410, and the amazing 510 after the war. The 110 began as a plywood experiment, a cheap high-performance boat, but its concept was to give the C.C.A. rulemakers fits a decade later when the 410 (35' 11") and the 510 (44' 75⁄8"), looking like boats from the moon, began fleet racing.

It was typical of Hunt that other projects were in the works in the years when the first Concordias and 110s were attracting attention. There were always other projects in the works, and they ranged from domestic contrivances, to rough sketches of neverbefore-seen types of boats, to fine details of gear and rigging. In 1939-40, Hunt moved his family into a house that Waldo Howland owned in Fairhaven, Massachusetts, and, in an arrangement made by Llewellyn Howland, began working on sailcloth at the Wamsutta mills in New Bedford. It was only a year of research and development before the war, but it was the beginning of modern sailmaking, and Hunt was one of its pioneers.

During World War II, the Hunts moved back to Cohasset, and Ray began to take an interest in powerboats. He became a lobster fisherman, first in an old rumboat, and then in a “Huntform” A Concordia yawl with spinnaker set, roaring downwind. workboat of his design that enabled him to set his gear farther off-shore and get back quicker than a conventional lobsterboat.

The Huntforms were predecessors of the deep-vee in that they had round bottom sections—a convex curve along the bottom that flared up and out in concave curves like the lips of a bell at the chine lines. A 39' Huntform workboat that Yachting showed in its design pages in 1945 was said to do 16-17 knots with a Chrysler Crown driving through 1.95:1 reduction, and a 54' Huntform of 1948, built by Graves in Marblehead for Bradley Noyes, cruised at 35 mph and topped out at 46 with a 1,500-hp Packard V-12. Perhaps the most interesting version of the Huntform hull was a 20' tank-test model for a destroyer that Charles Francis Adams persuaded the Navy’s Bureau of Ships to test. The Navy never took it up, but the BuShips technicians are reported to have been impressed; the model was said to have achieved the speed of a conventional slim destroyer, but—being beamier—was more stable at rest and had far less roll moving through test-tank seas.

The boating boom was on after the war, and Hunt set up a multifaceted business at Graves Yacht Yard in Marblehead. The Marblehead “sailing center” was involved in brokerage, new-boat construction, rentals of 110s, chartering the Hunt family’s 53' ketch

Zara, selling 110s and 210s, building dinghies for Boston’s Community Sailing Center, and sailmaking. It didn’t last for more than a few years, but the business was like Frank Paine’s design office as a magnet for new talents and ideas.

One of Hunt's champion offshore racing machines.

Photograph courtesy Bertram Yachts.

Ray Hunt found time for ocean racing during all of this, and among his triumphs in the 1940s and 1950s were beating the powerful

Baruna boat-for-boat with the 510 on the New York Yacht Club Cruise, winning the Vice Commodore’s Cup on the NYYC Cruise of 1950 with one of the Shoalers, sailing several Bermuda Races in

Zara, winning the New London-Marblehead Race three times for the Lambert trophy, winning the Annapolis-Newport Race in 1957 with

Harrier, his Concordia 41, as well as taking the Cygnet Cup in that year’s NYYC Cruise.

In the mid-1950s, Dick Fisher conceived the idea of a balsawood pram that would weigh about 15 pounds. “I never built it,” he said, “but in 1954 1 saw an announcement for a foamin-place foam kit. ‘Aha!’ I said, ‘Synthetic balsa wood’.”

Fisher and Bob Pierce built what they felt was an improved Sailfish out of foam and epoxy and showed it to Ray Hunt. “That’s all right,” said Hunt, “but if you want something to build in quantity, why don’t you try an outboard?” A good business judgment. What evolved was the 13' Boston Whaler, first as a Hunt design that resembled a little Hickman Sea Sled, then with variations of a central hull with sponsons on either side. “We put the third element into it, then Ray put in a different third element, then we tried another...” said Fisher.

The design of the Boston Whaler is a good example of how Ray Hunt often worked—a clear idea realized in a prototype, then modified with input from others.

During the late 1950s, Hunt was experimenting with a hull form that would revolutionize powerboating and make his name familiar all over the world. The idea of the deep-vee came from his experience with the Huntforms, from the new possibilities inherent in lightweight and high-rpm engines that came out of Detroit beginning in 1949, and from Hunt’s careful reading of Lindsay Lord’s

The Naval Architecture of Planing Hulls. He kept an annotated copy of Lord’s book in his office.

The first deep-vee was a 23' prototype built of wood by Charlie and Sam Wharton in Jamestown, Rhode Island. The boat had surface propellers and lacked the familiar lifting strakes, but it was a good test bed for the idea of a vee-section hull that could cut through the water without pounding. Something like the deep-vee boats we know today appeared when Bill Dyer made four fiberglass versions of the 23 for a new company called Essex Fiber Boat. One of them was sold to Jacob Isbrandtsen as a tender for

Vim during the America’s Cup summer of 1958, and Dick Bertram, Miami yacht broker and member of

Vim’s crew, took an interest in the boat and eventually acquired it. Bertram asked Hunt to design a 31' version, and he had the first one built of wood in Miami for the 1960 Miami-Nassau powerboat race.

The iconic Bertram 31, son of the famous deep-vee

Moppie.

Photograph courtesy Bertram Yachts.

At the same time, Jim Wynne had a 24' Hunt deep-vee built with Volvo sponsorship by Palmer Scott in Massachusetts and fitted with two 80-hp Volvo stern-drive packages. The tale has been told many times how Bertram and Wynne dominated that rough run to Nassau, finishing one-two while the rest of the fleet straggled in the next day. The previous summer, a 15'6" Hunt-designed deep-vee outboard driven by Jim Lacy and Ted Hermann had won the Around Long Island Marathon at an average speed of 34.2 mph. The deep-vee was launched by its racing success, and in 1961 the Bertram Yacht Company began a production run of the famous Bertram 31. Powerboat design, certainly in terms of numbers, has been dominated by the deep-vee hull ever since.

The genesis of the Hunt deep-vee was straightforward; its patent situation was more complicated. U.S. patent laws give an inventor a year’s time to file for a patent after the invention has been used in public or discussed in print. One day in the spring of 1958, V.B. Crockett, columnist for

Skipper magazine, visited Ray Hunt in his office in Padanaram, Massachusetts, and asked what he was up to. What he was up to was the deepvee, and he told Crockett all about it. The story ran in the July 1958 issue of

Skipper and was forgotten. Patent papers were finally filed more than a year later. Hunt found himself busy suing infringers of his patents in the early 1960s, and he was relatively successful until one of them discovered the article in

Skipper. At that point, the deep-vee became an idea with no patent strings attached. To add insult to injury, Ray Hunt had to pay one of the copyists $30,000 in damages, because the firm had gone out of business defending its patent infringement.

Ray Hunt suffered two disappointments in the late 1950s and early 1960s. The final blow was the loss of the deep-vee patent, but the first was Easterner’s failed America’s Cup campaigns in 1958 and 1962. Hunt’s only 12-Meter design was one of the handsomest Twelves ever launched, and although Easterner showed power and speed on occasion the yacht never performed consistently well. There were other triumphs to balance the disappointments. Ray Hunt revolutionized the design of 5.5-Meter boats in 1956 with

Quixotic, which he drew for Ted Hood and Don McNamara on the back of a manila envelope. Only a rigging failure kept her from sailing in the Olympics, and Hunt made up for the failure in 1960 with

Minotaur, which George O’Day and Jim Hunt sailed to an Olympic Gold Medal at Naples against the best of Einar Ohlson’s designs. In 1963, he won the 5.5 Worlds himself in

Chaje II, a boat he designed for Jussi Nemes of Finland.

This brings us full circle. Ray Hunt began his remarkable career as a savvy and sensitive helmsman, and this sensitivity to wind and water, and to the behavior of boats in both, was the essence of his genius as a yacht designer. Like Archimedes, he saw more clearly into the physical world than other men, and what he understood produced boats like the deep vees that were more to the point than anything that had come before.

In 1966, Hunt formed C. Raymond Hunt Associates in Boston with John Deknatel, and the firm produced designs for O’Day, HiLiner, Bertram International, and other boatbuilders as well as for private clients. During the 1970s he was experimenting with waterballast systems in a 21' HiLiner deep vee, a big trimaran for Phil Weld that was never built, a parafoil system to draw a boat along, plus special sailcloth from Howe & Bainbridge for the kite, and a 110 with the mast all the way aft and a big quadrilateral jib.

Ray Hunt was a powerful, creative force in the lives of the hundreds of people his enterprises and inventions touched. He died in the summer of 1978, but the enterprises and inventions are still with us, and it is likely that they will be influential—indeed, a powerful creative force in themselves—for generations. “For innovation in design,” Arthur Martin, founder of Martin Marine and the Alden Ocean Shell, said, “Ray Hunt will outshine them all.”

The late Joseph Gribbins was the editor of the long defunct Nautical Quarterly magazine. We publish this article with the kind permission of his widow Ethel Gribbins.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

C. Raymond Hunt Associates

5 Dover Street, New Bedford, MA 02740

508-717-0600;

www.crhunt.com

Hunt Yachts,

1909 Alden Landing, Portsmouth, Rhode Island 02871

401-324-4201;

www.huntyachts.com

Maine Dealer: Yachting Solutions

229 Commercial St., Rockport, ME 04856

207-236-8100;

www.yachtingsolutions.com

Ray Hunt, a first-class helmsman and an inventive,

Ray Hunt, a first-class helmsman and an inventive,  Ray Hunt’s 12-meter Easterner, beautiful but not quite competitive

Ray Hunt’s 12-meter Easterner, beautiful but not quite competitive Bow-on view of the revolutionary Boston Whaler.

Bow-on view of the revolutionary Boston Whaler. One of Hunt's champion offshore racing machines.

One of Hunt's champion offshore racing machines.  The iconic Bertram 31, son of the famous deep-vee Moppie.

The iconic Bertram 31, son of the famous deep-vee Moppie.