There is no more iconic Maine harbor than this one:

There is no more iconic Maine harbor than this one: Stonington, on Deer Island Thorofare. All photographs by Donnie Mullen.

Look at the iconic Maine harbor at sunset, after the afternoon’s onshore breeze has settled down. You might see any number of lobsterboats bobbing at their moorings, lined up in the light of the setting sun, and you might be comforted by thoughts of timelessness and tradition. A more knowledgeable observer would know something more. They would know that people who own and fish from those boats have, in the last 40 years, taken the knowledge of their fathers and grandfathers and built on it. They have taken the fishing business to a completely new level of technology and effectiveness. This is classic business innovation: to catch more, better, faster, and Maine fishermen are very good at it. At the same time, the vision of tradition and timelessness is what it appears to be. Maine fishing communities retain traditional values and knowledge that provide the seeds of a new kind of innovation much needed in an uncertain world where markets collapse because of remote events; where global climate change laps at the dock; where, in the last 30 years we have learned so much about the Gulf of Maine that we can no longer deny the fact that our actions can hurt the species and ecosystem we depend upon. Suddenly, having local food production looks like a security issue. To understand how transformative change could come from such a traditional industry first, a closer look at those traditions and practices.

Maine's lobster fishery defies conventional fishery management wisdom.

Maine's lobster fishery defies conventional fishery management wisdom. Pictured here: a working lobster wharf at low tide.

The Maine lobster fleet operates within what some economists might consider outdated traditional rules, since they limit the scale of the fishery. The fishery uses only traps; it protects breeding females, juveniles, and their habitat; and it limits the number of traps a person can have. All fishermen fish in a zone, within which there are numerous traditional territories. Entry to the fishery is controlled by a state-sanctioned apprentice system, which reinforces the personal responsibility each lobsterman has to live by the rules. Finally, every fisherman must be an owner-operator. Fishermen attribute this last measure with maintaining the local and community nature of the fishery. There are roughly 6,500 commercial lobster licenses in the state. Each license-holder pursues his or her personal goals, and each brings to the fishery their own unique gifts; they create, adopt, and adapt innovations in their own way. The fishery operates at a human scale where learning is direct and experiential and where knowledge of the resource and of fishing gear and boat use is first-hand. This has resulted in a fishery that defies conventional fishery management wisdom. Stocks are being sustained at record levels in the Gulf of Maine, thousands of people make their living by lobstering, and there is a constant tinkering and competition within the framework. The lobster fishery has adapted rapidly to the availability of new materials and technologies. For example, the fishery has modernized dramatically. Boats have gone from being built of wood to fiberglass construction, and some have now gone back again to wood, using new boatbuilding techniques. Fish finding has gone to the best sonar and plotters. The GPS system has revolutionized fishing by making it possible to return to a precise place in the ocean again and again. Even the simple lobster trap has been transformed by the adoption of vinyl coated wire; as wooden traps have disappeared, so too have the hours of labor needed to mend wooden traps, carry rocks to weight them, and pull traps up mid-season to avoid worm damage.

"Some fishermen get ahead because they keep their expenses low;

"Some fishermen get ahead because they keep their expenses low;others buy the biggest and the best and are able to catch more, faster."

Few “shore people” are aware that there are as many ways to make a living from fishing as there are people who fish, each using the particular mix of talents and aptitudes with which they were born. Some fishermen succeed because they can rig their gear just right for the creature they are chasing. Others work at the layout of work on deck so that tending gear becomes a finely choreographed art. Others make smart business decisions, knowing precisely when to buy a different boat, a new engine, more traps – or when not to do so. Some think like their prey: they know where the lobsters or fish or scallops are likely to be, and when. Some fishermen get ahead because they keep their expenses low; others buy the biggest and the best and are able to catch more, faster. Some focus on catching the most; others on pocketing the most profit when the season is over. Enter the challenges and questions of the twenty-first century: Can the fishing industry restrain itself and its powerful technologies so that we can fish forever right here in Maine? Can we reduce our carbon footprint? Can we sell and eat fish that are locally caught? Can the people who catch the fish become an effective voice for the health and diversity of the Gulf of Maine? Can the traditional knowledge, the creativity, and the persistent practical know-how of Maine fishermen contribute to transformative change in fishing? Can we use the fact that we live in small communities to build a sustainable future? Maine fishing has a lot to contribute precisely because it is still community-based and for much of the coast, communities are highly fisheries-dependent. Fishing matters, and thus, the knowledge is growing that conservation and taking care of the resource and the ocean and what runs off the land also matter. For people who catch things for a living, people with an optimistic, competitive, and outcome-oriented culture, it can be difficult to face and acknowledge the need for limits, but if you scratch the surface, you will find that knowledge is there in many of today’s fishermen. Take the Maine lobster laws. As each successive rule came in, it was not initially universally popular. But taken as a whole the rules are now supported, obeyed, and even a source of pride. A crab fisherman from North Carolina who visited here recently could not believe the hundreds of otherwise salable lobsters that Maine fishermen threw back into the ocean every day: juveniles, egg bearing females, v-notched lobsters, and oversized lobsters are put back alive to grow and reproduce. He said that Maine has a truly unrivalled foundation of conservation ethics.

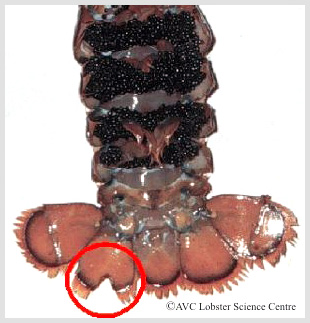

The v-notch rule is an excellent example. For decades, many Maine lobstermen conducted their own broodstock protection campaign, enforced by a state law that they supported. If a female lobster carrying eggs under her tail was trapped, the fisherman would cut a small notch in one of her tail flippers and release her. This way, not only was the female protected while she was carrying eggs, but she was protected for at least one or two more breeding seasons while the notch in the tail grew out. Maine fishermen did this for years, despite state and federal scientists and fishermen from other states who claimed it harmed the population or had no positive impact on the stock. Maine fishermen stuck to their guns, and more recent research has supported their claims that the practice contributes significantly to lobster-egg production. The rule has now spread to other lobster-producing areas. The territoriality of lobstering is another example. “The lobster gangs of Maine,” small groups fishing areas of inshore bays who protect their turf by excluding others, are sometimes viewed as a colorful idiosyncrasy of the fishery. In fact, this practice has tremendous functional benefit as a conservation tool. It is what is now called area management. At its core is a recognition that there are not enough fish for everyone to be able to work everywhere. Our inshore fishery has evolved as a local fishery. Most fishermen have earned their living near home, shifting among species as abundance and markets dictated. Traditionally, fishermen were involved with two or three different fisheries in any given year and as many as five or six during a lifetime. The current situation, where most inshore Maine fishermen are dependent on lobster alone is a more recent development, a result of the depletion of non-lobster resources such as groundfish and the loss of access to other fisheries due to federal regulation. A local fishery means each fisherman is an expert on his or her small piece of the Gulf of Maine. All ecology is local, and fishermen are observers of fine-scale events in that local ecology. Because this knowledge is non-scientific, it is called Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK). Fishermen are place-based ecologists who talk about “find the feed, find the fish” when they gather. Fishermen are the ones who are interested in where the smelt have gone, or what the impact of the loss of alewives is.

Ted Ames: Mainer, fisherman, innovator, scholar.

Ted Ames: Mainer, fisherman, innovator, scholar. The promise of TEK comes when this knowledge can be linked with modern science. When lifetime fisherman and scholar Ted Ames used computer mapping to plot historical fishermen’s observations, he combined science with his own knowledge of fish movements and behavior. The result was a new idea: that Gulf of Maine groundfish stocks are more local than previously thought. This idea has been a catalyst for a dramatic body of new research using genetics, tagging, and behavioral studies. This, in turn, has provided important new perspectives on how to manage fish, and starts to explain why the groundfish in the eastern Gulf of Maine have not recovered the way cod and haddock have in other areas. The same goes for gear innovation. Whereas in the past, the purpose of gear research was to improve the size of the catch, Port Clyde fishermen are now using their intimate knowledge of dragging to work with trawl gear experts. The goal is to minimize the bycatch of unwanted fish by making the gear more selective. In the markets, community action has stepped in when the complex supply chains of modern food distribution and the global credit system have failed small, remote communities. Community Supported Fisheries (comparable to CSA or Community Supported Agriculture, but where consumers subscribe to buy a certain amount of fish or shellfish direct from the fishermen), community lobster sales, and a revival of co-ops, have provided fishermen and consumers with better options during difficult economic times.

Fishing can be seen as a metaphor for the challenges we all face as we learn to live within the limits of the planet.

Fishing can be seen as a metaphor for the challenges we all face as we learn to live within the limits of the planet.Finally, in the global search for measurable stewardship and conservation, our owner-operator fishery also provides us with direct, personal accountability. On the water, far out of sight of land, it is the person towing the net, or hauling the trap, or changing the oil who directly impacts water quality and the fish stock. If you are a hired captain, you work for the company, meeting a production quota that is set independently of the conditions and situation you might encounter on the water. If you are an owner-operator, you may set high standards for yourself, but you also can think and act with long-term interests, and respond to local conditions. And if you lose your license, you lose your livelihood and business and possibly your house, not just your job. Lobstermen have for years supported the taking away of the license – the privilege of fishing – for conservation violations. Fishing can be seen as a metaphor for the challenges we all face as we learn to live within the limits of the planet. We have spent the last several hundred years innovating to be bigger, better, faster. Now, we are presented with a new challenge: how to be smarter at living within the ecological bounds of the planet on which we live. When a fisherman says, “the worst day on the water is better than the best day on land,” he is speaking about a basic connection with the natural world, something many people in urban areas yearn for. Maine fishermen, with their knowledge, their independence, and their care for the resources that provide their livelihood are a huge resource for Maine. Partnered with modern science and community values, the Maine harbors where they ply their trade can and should be a place where we can fish forever.