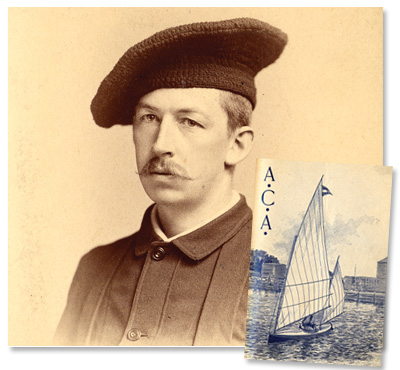

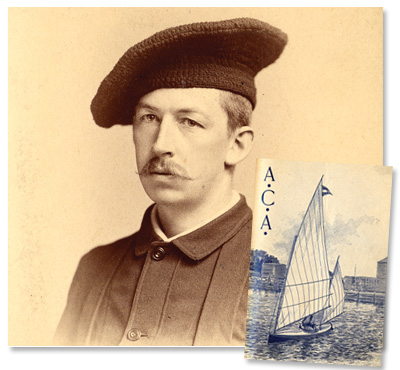

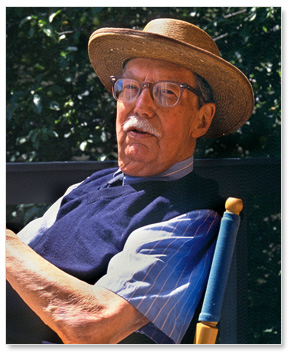

W.P. Stephens, dressed for a day on the water.

The sailing canoe, depicted here on the cover of

the 1889 A.C.A. program, is

Vagabond, designed by

Stephens and built in 1888. Credit: New York State Historical

Association, Special Collections(2)

This is the first in a series of short biographical sketches dedicated to remembering those who influenced how we respond to boats, ships, and the sea.

W.P. Stephens: The Dean of American Yachting

Also known in his later years as the Grand Old Man of Yachting, William Picard Stephens, born in Philadelphia in 1854, became involved in boating and yachting at an early age. As a young man he was active in competitive rowing, but after reading John MacGregor’s

Voyage Alone in the Yawl Rob Roy, he became an avid double-paddle cruising and racing canoeist. In 1873 he graduated from Rutgers University as a civil engineer; in 1878 he went to work at the John Roach shipyard, Chester, Pennsylvania, but being more interested in boats than ships, he founded his own canoe and small-craft boatbuilding shop at Rahway, New Jersey, in 1880. The following year he moved his business to West New Brighton, Staten Island, New York, where he became well known as a designer and a builder.

Stephens was a mover and shaker in the early American canoeing movement. One of the founders of the American Canoe Association in 1880, he won the first race at the inaugural ACA regatta at Lake George, New York, in his own sailing and paddling canoe Jersey Blue. Later, in 1895, a boat to his design, the 15-foot-waterline

Ethelwynn, defeated the Spruce IV, from England, in the first challenge for the Seawanhaka Cup.

W.P. Stephens contributed to the influential yachting and canoeing journal Forest & Stream, and in 1883 became that publication’s canoeing editor. He was one of the founders of the Society of Naval Architects and Marine Engineers, in 1893, and the editor of Lloyd’s Register of American Yachts, beginning in 1903. His books include

Canoe and Boatbuilding for Amateurs and

American Yachting, among others. His greatest achievement was the monumental book

Traditions & Memories of American Yachting, originally published serially in

Motor Boating magazine beginning in 1939.

When he passed away in 1946, age 91, he was typing what would have been the last installment of the series. He was of such importance to the history of yachting that many years later Mystic Seaport Museum named one of its principal annual awards after him.

“In the sanctum sanctorum where Mr. Stephens does his writing is a unique desk,” wrote Wade Ham de Fontaine about Stephens at work on

Traditions & Memories. “[It is] a large affair with the typewriter in the middle and with shelves and drawers on either side to accommodate the reference books and other tools of the writer’s trade. Behind his chair and within easy reach are row upon row of shelves lined with books—old books, new books, books on design, books on construction, on racing, on cruising and adventure on the high seas, and a complete collection of

Lloyd’s Register of American Yachts from Volume I to date.”

“A close study of records became necessary,” Stephens wrote about his task. “The further this was followed, the more fascinating it became. My own views of yachting have broadened materially. I have been led to live as far as possible in the past, and many periods and events which once seemed isolated and disconnected have revealed themselves as intimately related elements of a great whole.”

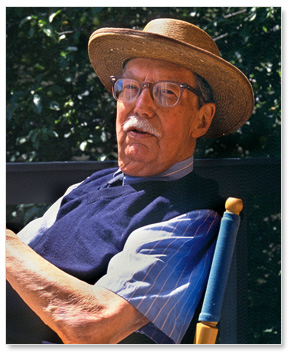

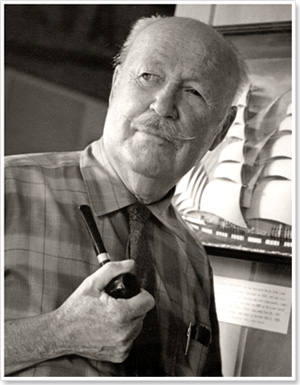

Henry Scheel at home in Rockport, Maine.

Photo by Ben Magro

Henry Scheel, also known as Harry, was born in Passaic, New Jersey, in 1911. Intending a career in boat and ship design, he studied naval architecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge. Following graduation he accepted a position at the Bureau of Ships in Washington, D.C., where he remained throughout World War II. After the war, in 1946, he opened a design office in New York City, specializing in custom and stock sailing and power yachts, and sport-fishing craft. His best-known designs during that period were a series of motorsailers built by the Stonington Boat Works in Stonington, Connecticut. During the Korean War he worked on submarine design at the Electric Boat Company in Groton, Connecticut, and then, in a drastic career change, dropped out of naval architecture and yacht design and went into the textile business.

In 1968, Henry Scheel returned to the subject he loved and took a position at Morgan Yachts in St. Petersburg, Florida, where he designed the various vessels being built for Disney World, then under construction. In 1971 he moved to Maine and established Scheel Yachts in Rockland. It was there that he developed the revolutionary Scheel Keel—a hydrodynamically shaped ballast keel that provided sail-carrying capacity, stability, and shallow draft without a centerboard. Patented in 1974, the Scheel Keel was a precursor to the famed winged keel used by the Australians to win the

America’s Cup.

Scheel was fascinated by hydrodynamics and, especially, wave-making. His favorite development technique was to use radio-controlled sailing models to study the behavior of his works in progress. In the years before his death, in 1993, Scheel designed several large yachts for the Royal Huisman Shipyard in the Netherlands.

Henry Scheel was a man of strong opinion. “Most people who come to me have a good idea of what they’re looking for,” he once said. “Otherwise, I’ve sent a number of people on their way. I won’t draw a boat for somebody who really doesn’t know what he wants.”

He also argued vociferously against stagnation in yacht design. “I would like to plant a seed,” he said not long before he died. “It is this: The old boats [that traditionalists] are building were at the pinnacle of their design and competence 100 years ago. Times have changed. You may continue the same type of development that resulted in the existence of these boats in the first place—for you can’t tell me that the original peapod is the peapod of today. That is to say, somewhere along the way, some peapod-builder said to himself, ‘This thing needs to be a little wider,’ so he made it a little wider, and so it developed into the fine piece of equipment it is today. You must continue that development.”

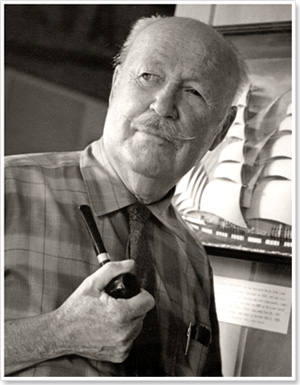

Hervey Garrett Smith in his studio.

Photo courtesy Long Island Maritime Museum

Born in Bayport, Long Island, New York, in 1896, Hervey Garrett Smith was as interested in art as he was in boats and the sea, and our world is all the better for it.

Smith attended the Pratt Institute in New York; after graduation, during World War I, he served as a flight instructor. Following the war he became a freelance artist, providing illustrations for several publications, among them National Geographic and the various boating magazines of the time. He also wrote and illustrated several books, including

The Marlinspike Sailor,

Boat Carpentry,

The Small Boat Sailor’s Bible, and

The Arts of the Sailor.]

Few twentieth-century writers could equal Hervey Garrett Smith’s works on the traditional arts of the sailor; none could surpass them. His descriptions of knotting, splicing, fancy work, canvas work, and the practice of marlinspike seamanship are clear, concise, and evocative. So, too, are his drawings, which are technically accurate, easy to follow, and a joy to behold.

The

Arts of the Sailor is Smith’s finest book, a compendium of information that if followed to the letter will make just another boat out in the harbor one of the shippiest on the coast. The topics run the gamut: the anatomy of rope, sailor’s tools, knots, hitches, splicing, whipping, wire and rope service, hand sewing, decorative ropework, chafing gear, reefing, towing, cleats, rope-stropped blocks, and making all sorts of gear, including rope mats, a heaving line, a bosun’s chair, and a ditty bag.

In print continuously since it was first published in 1953, the

Arts of the Sailor has helped and inspired several generations of sailors to keep alive the traditions of sailorizing.

“The urge to share one’s experience stirs within the breast of many men,” Smith wrote in the preface to The Arts of the Sailor, “and I am no exception; therefore I shall always be a self-appointed missionary, carrying the light to the dark places and preaching the gospel according to Matthew Walker.”

Peter H. Spectre is the editor of this magazine, the author of many books and magazine articles, and the creator since 1992 of

The Mariner’s Book of Days desk diary and calendar.

W.P. Stephens, dressed for a day on the water.

W.P. Stephens, dressed for a day on the water.  Henry Scheel at home in Rockport, Maine.

Henry Scheel at home in Rockport, Maine.  Hervey Garrett Smith in his studio.

Hervey Garrett Smith in his studio.