Photograph courtesy of NASA.

I like September. The foreign license plates are mostly gone, I can get a cup of coffee at Rock City Roasters without waiting, and the air is cool and clear, despite the vagaries of hurricanes and possible nor’easters. All seems quiet and serene, on land at least. But out in the Gulf of Maine, the calmness of summer is rapidly being replaced by the turmoil of fall.

We all know that the Gulf of Maine is a remarkably productive body of water. In terms of sheer biological mass, the Gulf has registered at the top of the charts for more than four centuries, despite the decline of recent decades. The Gulf of Maine provides food and shelter to dozens of marine mammals; scores of migratory and resident sea birds; and a wealth of marine vertebrates and invertebrates, from some of which, such as sea urchins and lobsters, we draw our living.

What’s interesting to me is that all this life, all this biological abundance, is based on microscopic plants and animals.

Plankton, from the Greek word for wandering, power the food chain. Phytoplankton are tiny plants; zooplankton are tiny animals. Trace the chain of predation for just about any animal found in the Gulf of Maine and at its base you will find phytoplankton. Phytoplankton draw their energy from the sun through photosynthesis. Zooplankton eat the phytoplankton and are themselves the food of other, larger animals.

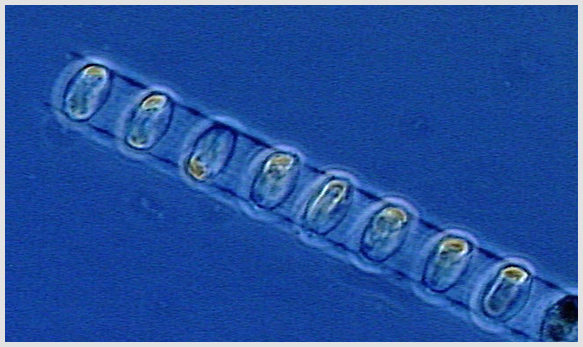

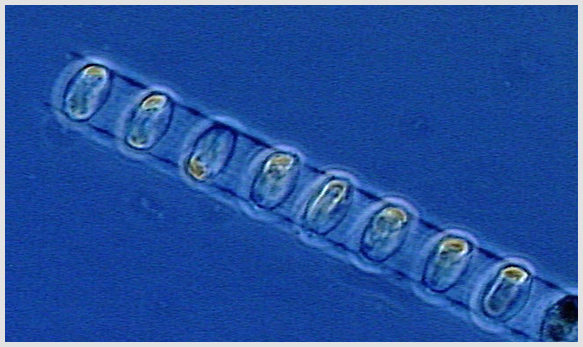

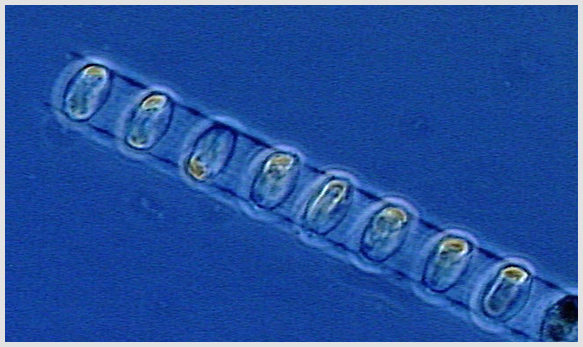

Photograph courtesy of NOAA.

For phytoplankton to grow and thrive there must be more than sunlight beaming down onto the ocean surface. Just like the plants in my rapidly-fading vegetable garden, phytoplankton must have nutrients in order to grow. Unlike garden plants, we can’t just dump a bag of 5-5-5 into the ocean and hope for the best. Phytoplankton need a peculiar confluence of sunlight, nutrients, and oxygen to thrive and reproduce.

Where do those nutrients, primarily nitrates and phosphates, come from? The principal sources are the many rivers that enter the Gulf of Maine. Carried in the water are literally tons of dissolved nutrients eroded from the land. In the spring, the discharge of meltwater flows many miles over the surface of the salty Gulf. When this occurs in April and May the sun is growing in strength. And, as we all may remember, spring in Maine usually involves a few fierce northeasterly storms, which dump loads of wet snow just as we are imagining crocuses and daffodils.

Those storms are critical to phytoplankton because from them blow strong winds, generally from the north and east, which push on the surface of the water, moving it to the southwest. This movement allows very cold, oxygen-rich deep water to move up to the surface, replacing the surface water; such an exchange is called upwelling.

Once the oxygen-rich water comes to the surface, it mixes with the nutrient-laden river water, and the strong spring sun bombards the mixture with sunlight. Conditions are now perfect for phytoplankton suddenly to grow and reproduce in multitude. This spring bloom powers the abundance of summer.

What you might not know is that this great bloom happens twice each year, not once. During the summer the Gulf of Maine stays fairly calm; cold deep water stays mostly on the bottom of the Gulf, and the warmer, now oxygen-depleted water stays on the surface. After a full summer of sunlight and phytoplankton growth, nutrient levels at the surface are low. The water is stratified and stable. But come fall, those pesky northeasterly winds start to blow again. The Gulf of Maine gets all roiled up.

At this time of year, however, there are no nutrient-laden rivers rushing into the Gulf. Phytoplankton must have nitrates and phosphates to thrive. So where do they get their food? In the fall, the nutrients come from below. The fall storms again push surface waters to the southwest. In this instance, upwelling brings waters up from the deep that are brimming with the necessary nutrients.

The deep bottom waters of the Gulf of Maine hold a mini-stockpile of nitrogen, phosphates, and other minerals drawn from dead and decaying plants and animals that sink down from the surface. Since there are so few organisms and no phytoplankton living way down deep, the nutrients contained within these remains are not gobbled up. They stay dissolved in the deep water. As the fall winds blow, that water rises once again to the surface. The sun is still quite strong in September and October, thus all the conditions are once again met for a big phytoplankton bloom. This bloom is not quite as large as in the spring but it is enough to stock up the oceanic larder for the winter.

I like the calm sunny days of September. Still, I realize that when our first northeasterly comes ashore those cold raw winds that rattle my windows and cause me to wear socks again are fuel for yet another spurt of life in the Gulf of Maine.

Photograph courtesy of NASA.

Photograph courtesy of NASA. Photograph courtesy of NOAA.

Photograph courtesy of NOAA.

Photograph courtesy of NASA.

Photograph courtesy of NASA. Photograph courtesy of NOAA.

Photograph courtesy of NOAA.