All photos by Polly Saltonstall

Boathouses, barns, and museums along the coast are stuffed with classic old vessels. Paper lines plans and records exist for some, but many were built based on half models or intuition, and the work of documenting them has been an important and evolving process.

In the early days historians and museum curators used tape measures, and more recently expensive laser scans to document old boats. But these days, a technology called photogrammetry has made the process way less complex, costly, and time-intensive.

That’s where retired General Motors auto engineer David Cockey and his wife, Katherine, also a retired auto engineer, come in. Small boat connoisseurs—David has been the president of the Museum Small Craft Association—they have been using photogrammetry for the past decade to create incredibly detailed 3D computer images of historic vessels in Maine and elsewhere.

Photogrammetry involves taking multiple, overlapping two-dimensional photos of an object and using triangulation to create a three-dimensional model. The concept has been around since the mid-1800s, and cartographers used it to make maps from aerial photos in the 1920s, Cockey said. But it’s evolved a lot since then. These days, computers and software allow hundreds of photos to be quickly transformed into detailed spatial models that can then be used to create line plans, as well as document a boat’s condition in time.

“It’s especially useful on traditional boats where a lot of times there are not original plans,” Cockey said.

The Cockeys’ recent work has taken them to New York State’s Adirondack Experience (formerly the Adirondack Museum), where with the help of former Penobscot Marine Museum curator Ben Fuller, they have documented 90 classic Adirondack guideboats and 13 canoes.

In Maine, they have documented peapods, among other vessels. An early project was taking the lines of the historic wooden sardine carrier the Jacob Pike. That record became especially important when the Pike was essentially destroyed after sinking a couple of years ago.

Cockey also has worked with boatbuilders, both as a naval architect helping design models and in using photogrammetry to aid in rebuilds. He used the process to come up with a 3D model of a lobster yacht under renovation at Hylan & Brown Boatbuilders, for example. The modeling helped the builders figure out where and how to add a cabin to the boat and electrify the engine, he said.

A photogrammetry model of a Pulsifer Hampton tender resulted in CAD lines used to make a half model that builder Dick Pulsifer said was the most accurate one ever made of his iconic wooden tenders, according to Cockey.

He also has used the process to provide data for Coast Guard certification of weight loads for various commercial tenders.

Cockey has been fascinated by boats since his childhood growing up in Baltimore. He read Howard Chapelle’s many books on yachts and yacht design and Anthony Bailey’s Thousand Dollar Yacht, which introduced him to classic boat guru John Gardner and his column in National Fisherman.

Eventually he wound up at a boat workshop at Mystic Seaport, where he met the museum’s then small boat curator, Ben Fuller, and his wife, Leslie, leading to a lifelong friendship and many collaborations. Regular visits with the Fullers in Maine eventually led to the Cockeys buying a house in Rockport, Maine, in 2014 and moving there year-round in 2016.

Although he wanted to be a naval architect and earned a master’s degree in naval architecture from the University of Michigan, Cockey received a doctorate in aerodynamics at Princeton University, which led to a career working in automobile design at General Motors in Detroit. He started working on auto aerodynamics, moved to the advance engineering staff, and eventually a job overseeing new vehicle programs. Models he worked on include the Chevy Equinox, the Saturn View, Cadillac SRX, and Pontiac Torrent. He still drives GM cars, but he left the company in 2009, accepting a buyout while GM was going through bankruptcy proceedings.

An interest in how to take the lines off old boats took him to a 2012 symposium in San Francisco organized by the National Park Service, where he learned about photogrammetry. In addition to his work documenting boats, Cockey has found time in retirement to get back to his first love: boat design.

He’s worked on several projects with Clint Chase at Chase Small Craft. Based in Saco, Maine, Chase designs and builds kits for small wooden boats.

Cockey has helped design the hulls for Chase’s Calendar Island 18 and 20 kits. And when Chase wanted to work on a kit for a catboat (not yet completed), Cockey used photogrammetry to capture the hull shape of a boat designed by Ned McIntosh for which no plans existed.

“His interest seems to be mostly in hull shapes,” Chase said. “Then I finish with the rest of the design work, like the interior, the rig, the foil shape. And from that I draw the plans. It’s worked out great for me.”

When documenting a vessel, the Cockeys place it on a table or stand and take hundreds of overlapping photographs from all sides. They then load the images into a computer program that identifies the same points in multiple images. Taking into consideration the camera’s position, focal length and lens distortion, the program triangulates one point on the boat with the different camera angles. When that point and literally millions of others are located in more than one image taken from different locations, the computer program can calculate coordinates and construct a 3D model, Cockey explained.

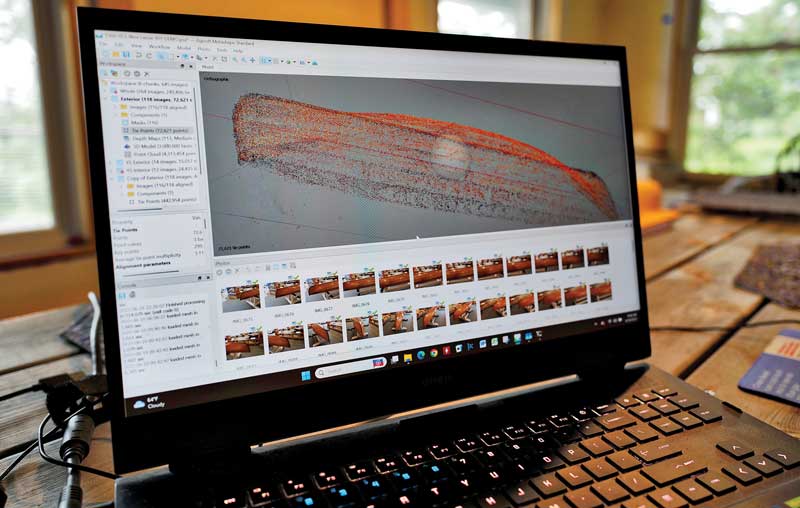

It’s a complex process to understand without visuals. During a recent visit, Cockey opened his laptop and demonstrated the different steps. First, he showed the final product, in this case, a color view of a 10-foot-6-inch Rushton canoe built in the late 1800s and now in the collection of the Adirondack Experience. As he moved his mouse, the orange canoe swiveled on the screen, rotating to reveal its curved interior, and the sinuous lines of its gunnels and keel. As Cockey zoomed in, the uneven grain of the canoe’s interior planking was magnified on the screen.

The process of documenting this canoe began with taking 264 photos from all sides. Cockey’s next screen view shows multiple, overlapping blue rectangles representing those photos clustered in a vague boat shape. The next screen shows a cloud of what Cockey explained are 4.3 million dots showing the general shape of the canoe. The photogrammetry software transforms those dots into tiny flat surfaces which it stitches together to create the final 3D image. Once this process is complete, Cockey can zoom in on any part of the canoe from any angle that he chooses.

This proved helpful when documenting another boat at the Adirondack museum. The photogrammetry process revealed that the boat’s transom, a single piece of wood, was not symmetrical. Cockey was able to understand based on the 3D image how the builders compensated for the distortion as they planked the vessel so that by midships the planking had become even on both sides.

Key benefits of the process, according to Fuller, are the speed with which a vessel can be rendered: an hour or two compared to a day or more using laser scanning or hand measuring. In addition, the detail in the final image documents the condition of the boat at a point in time, something museum curators like to track.

“It’s a record that will allow you to map deterioration and changes in the artifact,” Fuller said, “and you get that information really quickly.”

The resulting digital files also can be manipulated to show, for example, what a hogged boat might have looked like when new. “Research-wise it’s really interesting,” he said. “You can run your hypothesis out on the computer.”

Cockey uses a Cannon R7 to take his photos, but the process doesn’t require a fancy camera; an iPhone works equally well, he said. Key requirements include placing a yard stick in photos so the program can compute scale and making sure the boats being documented have rough surfaces that allow the computer program to differentiate points

“We like grubby boats,” Cockey says. If a boat is too clean, Katherine sometimes has to spray it with a mixture of chalk and water to create enough texture for the photos. Her role in the process also includes record keeping and working with students whom Cockey trains in the technique.

The art of boatbuilding continues to evolve, but thanks to engineers like the Cockeys and sophisticated digital technology the work of boatbuilders from the past is being documented and preserved.

✮

Polly Saltonstall is MBH&H’s editor at large.