All photos courtesy Jack Ledbetter

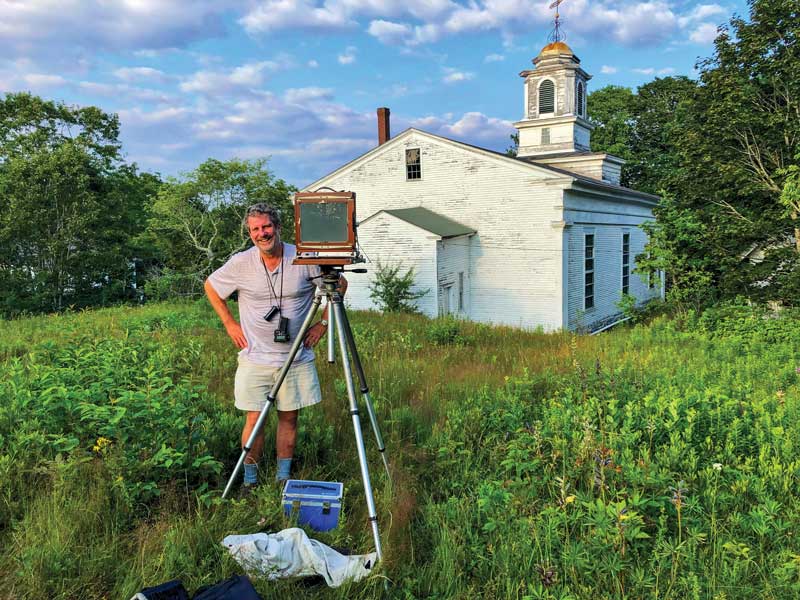

Some years ago, on a family trip to Baker Island, one of the Cranberry Isles, as we walked out onto the “dancing rocks” on the far side, we encountered a man with a very large camera on a tripod standing on one of the granite ledges. The camera, a large format wooden Deardorff, was aimed toward Mount Desert Island and the photographer appeared to be waiting around for something, checking his watch, studying the view.

This was Jack Ledbetter preparing to seize the perfect light. For many of his vistas, that’s Ledbetter’s modus operandi: to find that moment when the illumination is just right and then open the shutter.

The photograph Ledbetter took that day is one of many panoramas of the Maine coast by this consummate camera artist, in over 40 years spent exploring his adopted home. While he has also photographed Mount Katahdin and other settings, coastal views are his specialty, acclaimed for their clarity and composition.

While surrounded at home on Mount Desert by Acadia National Park, Ledbetter avoids it in the summer when the crowds show up. He recalls how he’d have to wait for visitors to disperse before getting a shot of the Bass Harbor Light, an iconic subject that makes for a fine sunset picture. If he does venture into the park, it’s apt to be to a less frequented spot like Little Hunters Beach.

Ledbetter prefers going to the offshore islands where there are few distractions and exceptional vistas. Frenchboro has been a regular destination, its working harbor a welcome respite from the hubbub of the mainland. He keeps a small Boston Whaler in Northeast Harbor, which allows him to camp out on nearby islands where he can catch both sunrise and sunset. He has also ventured further afield, to Matinicus and Criehaven on the outer edge of Penobscot Bay.

After four decades photographing Maine, Ledbetter continues to find new places. He mentioned Harriman Point Preserve in Brooklin, managed by Maine Coast Heritage Trust. Since discovering this picturesque coastal prospect a few years ago, he has been back more than a dozen times.

Ledbetter has a story for nearly every photo he’s ever taken: the time, the place, the circumstances. For his portrait of Pancho Cole, an early College of the Atlantic graduate who stayed on Mount Desert Island to work in IT, he joined him on his Luders 16 sailboat. In bowtie and suspenders, Cole concentrates on the wind and sails. Ledbetter has another photo of his former assistant, photographer Sarah Butler, in a boat built at her family’s boatyard at the head of Somes Sound. He has been slowly assembling a series of portraits of individuals with traditional boats.

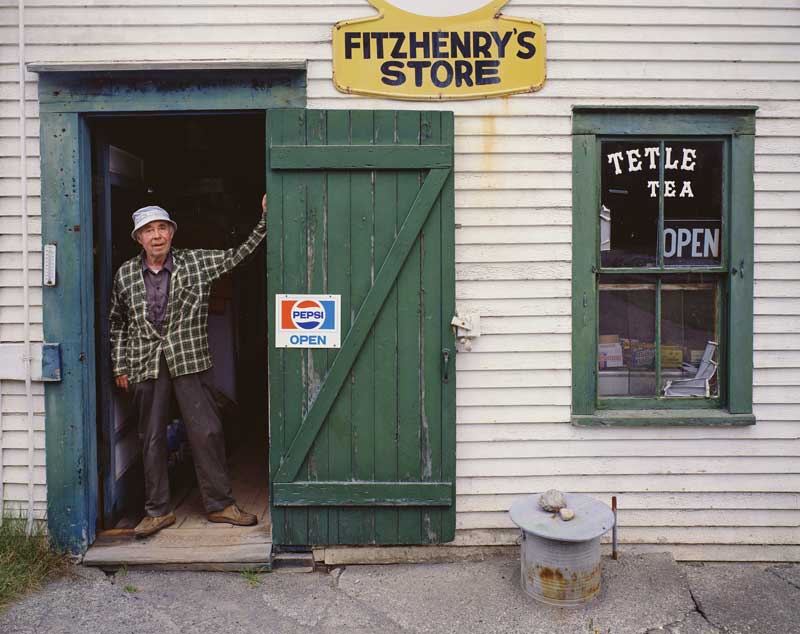

Over the years Ledbetter has gone out of his way to photograph older buildings in Maine, drawn to their character and what they represent in a community. “In an odd way,” he explained, “you want to photograph things that need a little paint on them.”

The First Baptist Church in Sedgwick is such a structure. A prime example of Greek Revival architecture, the weathered building was on its way to collapse when the Sedgwick-Brooklin Historical Society set out to save it. The church is in better shape these days, Ledbetter reported, thanks in part to a 2023 grant from the Maine Community Foundation’s Belvedere Historic Preservation and Energy Efficiency Fund to restore its roof.

Asked about his personal pantheon of favorite photographers, Ledbetter mentions some of the giants of American photography, among them, Paul Strand, Ansel Adams, Eliot Porter, Lee Miller, Saul Leiter, William Eggleston and F. Holland Day. The last-named, known for his pictorial style, has influenced Ledbetter’s own soft-focus studies of nudes.

Ledbetter also looks to Winslow Homer and Andrew Wyeth for inspiration. “They are Maine,” he said, “and when I see their images, I’m blown away.”

In June 2024 he attended “Picturing Maine: The Wyeth Family in Historical Context,” a week-long program hosted by the Farnsworth Museum and led by Victoria Wyeth, Andrew Wyeth’s granddaughter, and Margaret Creighton, Professor Emerita of American history at Bates College. One of the highlights was walking through the little farmhouse in Cushing where Wyeth lived and visiting his studio, a small space in the yard. “There’s still a jacket laying over the easel,” Ledbetter recalled.

A Southern Upbringing

Ledbetter was born in Albany, Georgia, near the Florida border. His family once farmed pecans and various row crops, including cotton, peanuts and, in wintertime, wheat.

Diagnosed with dyslexia, Ledbetter was sent to Aiken Preparatory School in South Carolina. As it turns out, the boarding school had a very good photography program. One of his teachers, Tish Meyers, taught him how to use the dark room in sixth grade. He had a 35-millimeter Agfa Rangefinder camera courtesy of his parents.

In seventh grade Meyers and her husband, science teacher Douw Meyers Jr., invited Ledbetter to spend August with their family in Christmas Cove, their summer home in South Bristol, Maine. A University of Maine graduate, Mr. Meyers remained connected to the state.

Compared to Georgia, where the heat forced one inside to fans and air conditioning, they went sailing nearly every day, making trips to Monhegan and elsewhere. Ledbetter found it mind-boggling—and his impressions of pea soup fog and glorious sun stayed with him.

Ledbetter attended a community college in Albany, Georgia, studying the three Rs. His family wanted him to have that foundation before he went off to pursue photography. Which he did: At age 20, he moved to New York City to study at the International Center of Photography.

Founded in 1974 by Hungarian-American photographer Cornell Capa, the school on Fifth Avenue and 94th Street was new and exciting. A number of renowned Life magazine photographers, including the founder’s brother, Robert Capa, were still around. Guest lecturers included such luminaries as Alfred Eisenstaedt.

“It was a magical time,” Ledbetter recalled. Armed with a 4-by-5 Graflex camera and later a compact Toyo View, he explored the city like a tourist, taking photographs of landmarks, Central Park, the Brooklyn Bridge, and the like. He remembers getting high marks for a photo he took of the Statue of Liberty as seen from the back.

After a year and a half, Ledbetter returned to Georgia and started doing commercial work. He took photographs for a manufacturer of crop dusters (one of his shots ended up on the cover of a trade magazine) and did work for politicians, through an ad agency.

Bored to death, Ledbetter questioned whether he wanted to stay in Georgia for the rest of his life. After serving as teaching assistant for a Parsons School of Design landscape photography class at Lake Placid in 1983, he decided to head to Maine to visit his friends in Christmas Cove. On that trip he drove to Lubec and was wowed by the downeast landscape.

On his way back, Ledbetter stopped for a few nights on Mount Desert Island, his first visit to his future home. He was amazed by the access to public lands and the sheer beauty of Acadia. He also thought there might be a market for landscape photography if he returned.

Back in Georgia, Ledbetter couldn’t get Maine off his mind, so in July 1985, he made a fateful decision, to head north and take his chances. Considering it was the height of summer, he lucked out and found a bungalow to rent from lobsterman David Thurlow in Bass Harbor through Harriet Whittington at the Knowles Company in Northeast Harbor. “The stars do align,” he said.

Ledbetter returned to that same spot the following summer, happy to be in the north and surrounded by a wealth of motifs. He remembers at the time that many of the traps on the Bass Harbor wharf were still wooden as were some of the lobsterboats. He relished this sense of history.

That year Ledbetter decided to stay for the winter. He eventually bought an old schoolhouse in Tremont, but never stayed in one place for that long, moving around the island over the years.

Looking for a gallery to represent him, Ledbetter was directed to Aurelia “Thistle” Brown, who owned Wingspread Gallery in Northeast Harbor. He laughed in recollecting how Thistle was more interested in the canoe on the roof of his truck than his photographs, but she took him on—and they went canoeing.

Brown put Ledbetter “on the fast track” to connecting him with Mount Desert Island’s wealthy summer community. He mentions with pride that two estates in Seal Harbor own 50 of his prints. She also taught him the ways of a gallerist, which helped him when he set up his own shop at the end of Main Street in Northeast Harbor in 1991. The space includes a dark room, a set-up for framing, and walls to display his work—a place to welcome what he modestly calls “a small but loyal following.”

One of Ledbetter’s collectors, the late art historian John Wilmerding, purchased a number of photographs over the years. When he ran out of wall space, he donated pieces to the Farnsworth and Portland museums. He also commissioned Ledbetter to photograph one of his favorite structures, the Charles Bulfinch-designed meeting house in Lancaster, Massachusetts.

David Rockefeller provided another commission, a photographic record of the Rockefeller Garden, which had been created between 1926 and 1930 by Abby Aldrich Rockefeller and famed garden designer Beatrix Farrand. For a year Ledbetter had carte blanche access to photograph the grounds. The prints are in the Rockefeller family archives in Tarrytown, New York.

Rizzoli published a coffee table book of Ledbetter’s photographs in 1989. The photographer dedicated Maine: The Coast and Islands to his mother “who gave me both the means and the motivation to carry though this project.”

When he isn’t visiting an outer island, Ledbetter can be found in his shop, developing film—he still uses a dark room—or sending files off to New York City for scanning. He still does commercial work to help make ends meet, including portraits, weddings, and special places. He also devotes time to organizing exhibitions for the Wendell Gilley Museum in Southwest Harbor.

Ledbetter bought his first digital camera in 2010 after being satisfied by the quality of prints. Today, he owns a “very serious” Fuji—and likes the “instant gratification” after years spent in dark rooms or waiting for prints to be processed in a distant city.

Ledbetter maintains a Georgia connection, spending six weeks or so in Albany each year to “recharge his batteries,” but Maine is his home and principal muse. Every September he rents a house in Christmas Cove where the magic began some 60 years ago. There’s no Wi-Fi in the house, which is just fine with him.

✮

Carl Little’s most recent books are the monograph John Moore: Portals (Marshall Wilkes) and Blanket of the Night: Poems (Deerbrook Editions). He curated the exhibition “Quarries: Muse and Material” for the Monson Arts Gallery in Monson, Maine, which runs through October. Little thanks Sarah Penley for finessing the images for this article.

For More Information

You can see more of Jack Ledbetter’s work on his website, jackledbetterphotography.com.