Much of an island’s allure is its remoteness and the adventure of getting there. Finding ferry schedules and figuring out what to bring and be without in these water-bound places are part of life offshore, and excitement builds as the journey’s different pieces fall into place.

That pull has drawn me to Scotland’s Inner Hebrides and Orkney Isles, and the Canadian Arctic’s Cornwallis, Baffin, and Ellesmere islands, which I reached alone by bush plane in late winter. The ice-class motor vessel Caribou took my husband and me in early spring to Newfoundland. Another year, we ventured aboard the Grand Manan V to New Brunswick’s Grand Manan Island.

That lifelong draw was planted on my first boat ride as a newborn to Maine’s Cranberry Isles in 1956. I don’t remember the inaugural ride, but a foggy night stands out in my mind from the 1960s. My parents, brother, and I arrived at the Lower Town Dock in Southwest Harbor on Mount Desert Island. Peering down the gangway, only the Vagabond’s red, green, and white running lights were visible in the swirling fog. The throb of the wooden passenger boat’s steady engine was comforting to hear in the dark.

Helping us aboard was Capt. Elmer Spurling. Clad in a fedora, tan single-breasted raincoat, and leather tie shoes, he and his wife, Eleanor, had been out to eat before fetching us and setting out for Little Cranberry Island. The passage signaled the start of my family’s summer-long stay there.

In mine and many others’ lives, that 3-mile boat ride has been repeated countless times. The Cranberry Isles, composed of five islands, lies just southeast of Mount Desert Island. Incorporated in 1830, only two of the town’s islands, Little and Great Cranberry, are inhabited year-round.

Since the Cranberries were settled in 1762, a great variety of passenger vessels, captains, and crew have served them. In the late 19th century, Little Cranberry’s Capt. Gilbert Hadlock launched a passenger service whose steamboats, Florence, Agnes, and Islesford, ferried islanders, summer folk, and day-trippers. In the 1930s, Capt. Eber Spurling began carrying the mail to the islands in his launch, the Jerry.

“With evocative names like Vagabond, Island Queen, Bobcat, Rogue, and Sea Queen, these boats and their legendary captains endured the fog, cold, and uncertainty of the sea to link our islands with the mainland,” wrote Great Cranberry Island Historical Society president Philip Whitney in the Cranberry Chronicle in 2015. Captain Eber Spurling, he wrote, “could steer a boat through the thickest fog and always land you safely.”

Nowadays, daily, year-round passenger service is provided by Beal & Bunker, whose Sea Queen and Double B depart from Northeast Harbor. Cranberry Cove Boating Co.’s seasonal ferry, the Sutton, serves the islands daily from May to October from Southwest Harbor, and its commuter boat, the Miss Lizzie, makes two daily runs in the fall, winter, and spring from Northeast Harbor. Captains John Dwelley and Blair Colby’s water taxis, Delight and Cadillac, also shuttle people to and fro.

Retired boatbuilder Ed Gray hasn’t forgotten the stormy Thanksgiving Day in 1957 when the island’s strong tug compelled his parents to take his sister Mary and him from their Connecticut home to Maine to spend the holiday with their grandparents who had retired to Great Cranberry. When they arrived in Southwest Harbor, it was blowing at least 50 mph.

Island fisherman Royal “Tinker” Colby met the Grays in his lobsterboat. Gray and his sister, Mary, had life jackets on. Their parents, Al and Bobbie Gray, were concerned about their daughter. A polio survivor, Mary wore a metal waist- and single-leg brace. They feared her heavy braces might weigh down and upset the small craft in the rough seas.

“The trip across was in the dark. It was very, very cold. My father had his hands on top of the boat’s shelter [to brace himself] and they got covered in ice,” Ed Gray recalled. At Great Cranberry, six island men were waiting to steady the tossing lobsterboat alongside the wharf and get the family ashore.

Like his parents, Ed Gray eventually made the island his permanent home, where he and his wife Jane raised five children. In 1979, he and Maine boatbuilder Jarvis Newman founded Newman & Gray to build fiberglass boats and restore classic wooden craft. Newman & Gray is now owned by Ed’s sons, Josh and Seth. They, too, were lured back to the island after earning college degrees and starting careers elsewhere. Josh’s wife, Lauren Gray, cultivates oysters.

Little and Great Cranberry, Baker, Sutton, and Bear islands have longstanding summer residents. Some of their ancestors began vacationing there in the late 19th century. Mostly from New England, the doctors, lawyers, clergymen, and college presidents were captivated by the wild, unique beauty combining sea and mountains. They sought a more rustic vacation than Newport, Rhode Island; Hyannis, Massachusetts; the Hamptons in New York; and other opulent seaside resorts on the Eastern Seaboard.

Newbery Medal Award-winning novelist and poet Rachel Field was among them. In 1910, she ventured to Sutton Island and stayed in a rented cabin atop cliffs on the northeastern shore. Then and now, the island’s seasonal residents schlepped their suitcases, groceries, and other supplies in wheelbarrows and carts from the landing, over mossy, knotted-root, woodland paths, to their cottages.

Eventually, Field acquired her own cottage.

“After the motorboat had chugged us across from Northeast Harbor to Sutton, Rachel [Field] would insist on trundling the luggage up to ‘The Playhouse,’ as she called her cottage, on a huge wheelbarrow,” author Robin Clifford Wood wrote, quoting one of Field’s guests in her biography/memoir The Field House. “Tall and vibrant, pushing back her auburn hair as she talked, her gray-blue eyes sparkling, she vehemently refused any help in pushing the wheelbarrow, and we made our way to ‘The Playhouse’ in its wake.”

For Audrey Delafield, Little Cranberry has been the thread in her family’s life. Her late father, Capt. Egerton Sawtelle, was a civil engineer and navigation expert who served at U.S. Coast Guard bases in New England. As children, she and her siblings spent the summer on the island. Back then, her family drove from Freeport to Southwest Harbor.

“In Ellsworth, we would call Elmer [Spurling]—God love him—and he would be there waiting at the dock,” the Scarborough resident remembered. “He always wore a khaki shirt and trousers.”

Spurling ferried the Sawtelles in his brass-hooped launch, Hobo. At Little Cranberry, general store proprietor Emerson Ham was waiting to convey the family on its final leg. Backing his old pickup truck down the dock, the droll-humored storekeeper greeted kids and adults with his deadpan quips and delivery. For summer kids, straddling the pickup’s side walls, tailgate, or piled baggage was thrilling as the vehicle bumped over dirt roads. From that moment, they were liberated from their structured mainland lives.

“We were just in heaven. We roamed free and biked all over the island,” the 83-year-old Delafield remembered. “Just kid’s stuff with no parental interference.”

Elmer Spurling had a corner on Little Cranberry’s passenger and freight business. But Great Cranberry’s entrepreneurs Clarence Beal and Wilfred Bunker launched a year-round passenger and freight service from Southwest Harbor in 1950. They secured the U.S. Postal Service’s contract to deliver mail to both Great and Little Cranberry.

Beal & Bunker trained generations of deckhands. They included Chuck and Rob Liebow. Save for Bunker and his son David, the Liebows together may have logged more sea time than any other crew driving the 75-year-old enterprise’s vessels.

A home movie shows the Liebows, their elder brother, Paul, and parents crossing from Mount Desert Island in Beal & Bunker’s Malesca to check out a potential summer cottage on Great Cranberry in 1955. It didn’t take much for Averill and Carolyn Liebow to realize the 2-mile-long island would be a safe place to cut their boys loose in summer.

A rude awakening led to Rob Liebow’s first paid job and launched his lifelong career captaining boats seasonally. One summer morning, the 13-year-old was awoken by “loud bangs” on his bedroom door on Great Cranberry. The door banger was Wilfred Bunker, who was short a deckhand. Liebow could row and tie a bowline. He scrambled out of bed to make 70 cents an hour on the mailboat. In his subsequent training, a major milestone was transporting a utility crew in the company’s open-cockpit launch, Tripet, for the first time alone and in pea-soup fog.

“It was so foggy you couldn’t see the end of your nose. He [Wilfred Bunker], for some reason, knew I could do it,” the recently retired Massachusetts school superintendent mused. “I didn’t know I could do it.”

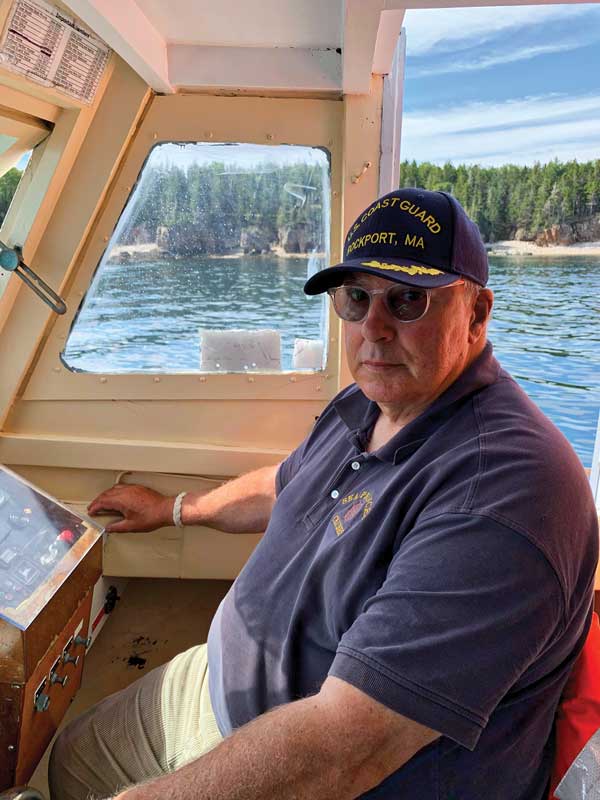

Parallel to his boating life, Liebow has worked as a teacher, coach, and administrator at schools in Maine and Massachusetts. Now 70, he has returned to Great Cranberry every summer, and driven the Sea Queen and nearly all the company’s other craft. The seasonal switch from helming schools to boats gets him out of the office and out to sea.

Come summer, Liebow still captains one of Beal & Bunker’s late night-runs to the Cranberries. He keeps his oar in the ferry business because he enjoys driving the wooden vessels and interacting with passengers whom he has known for years.

Like Rob, Chuck Liebow learned invaluable lessons as a deckhand. Bunker taught him how to pick up a mooring safely while singlehanding the 44-foot Sea Queen and other large boats.

“If you are out there by yourself, going out on the bow can be problematic. I think Wilfred [Bunker] went over twice,” he said.

The 74-year-old captain worked for Beal & Bunker on and off for over 50 years. He also ran his own island boatyard, drove former U.S. Secretary of Defense Thomas Gates Jr.’s picnic boat, Jericho, and ran a passenger ferry between the Cranberries and Southwest Harbor.

On the ferry Island Queen, a blue-fronted Amazon parrot named Barney screeched raucous comments from Chuck Liebow’s shoulder. The captain’s sure-footed Cairn terrier also entertained passengers. Small, but agile, Teagan patrolled various passenger boats’ gunnels.

Over the years, the Liebows trained many deckhands to tie knots, handle mooring lines, maintain logs, and other essentials. Among them were Joe Flores and his elder brother, Paul Hewes. The brothers started as deckhands at ages 11 and 14, and eventually they and their sister, Casey Gustafson, took over Beal & Bunker in 2019.

“You could tell he was going to be good at it,” Rob Liebow said of Joe. “He was cautious. Didn’t take chances. Listened to what you told him.”

Like his brother Paul, Flores earned his captain’s license. Now, he is showing the ropes to another generation. The deckhand’s job entails handling the U.S. mail, punching tickets, shoveling snow, and wiping damp outdoor seats. They dispense dog biscuits and assist people with their groceries and baggage. They also interact with island kids, some of whom commute daily year-round.

Cranberry Isles’ school children attend either Great or Little Cranberry’s kindergarten through eighth grade Longfellow and Ashley Bryan schools. The schools alternate schoolhouses every two years.

One mid-January morning, Audrey Sumner made her way down slick wooden steps to Beal & Bunker’s Double B, rocking beside Great Cranberry’s town pier. “Good morning, princess,” Flores greeted the 10-year-old from the helm.

Sumner was headed to school on Little Cranberry. The frigid northwest wind blew over 20 mph, but she was unperturbed as the Double B pitched back and forth during the 15-minute ride. Rough to her meant a “three-ringer”—when the vessel’s bell rings three times—as the boat plows through steep waves.

Sumner has been to many other islands. She rode on Maine Seacoast Mission’s vessel Sunbeam to visit Frenchboro, off Mount Desert Island. She has traveled to Monhegan Island, Isle au Haut in Penobscot Bay, and Casco Bay’s Cliff Island. She has even been to Cuttyhunk, the outermost of Massachusetts’s Elizabeth Islands in Buzzards Bay.

While she loves making new friends and exploring other islands, Sumner’s anticipation grows as she spots the Bear Island Light and other familiar sights on the return trip to Great Cranberry. She told me, “I always come back and kiss the floor.”

✮

Letitia Baldwin is a freelance writer who lives in the downeast towns of Gouldsboro and Cranberry Isles. She previously worked as the Arts & Leisure Editor at The Ellsworth American and style editor at Bangor Daily News.