“I like straight lines,” Diana Roper McDowell explained. “They’re calming.” In her remarkable watercolors, McDowell uses those lines to transform landscapes, figures, wildlife, boats, and other subjects into compelling designs. She calls her particular approach “abstract realism.”

McDowell’s paintings are often prompted by something witnessed in the immediate vicinity of her home in Lamoine. For example, A Maine Sunrise for Ukraine began one early summer morning when she awoke to a spectacular sunrise. “I jumped out of bed to get some photos before the light changed,” she recalled. The intense yellow and deep blues brought to mind the Ukrainian flag; as their war had been on her mind, she honored that country in the painting’s title.

Another watercolor, Worm Digger III, pays tribute to one of the hardest working individuals on the coast of Maine. McDowell has painted this figure several times, drawn to the shapes and colors of the scene—and the fact that he’s wearing one reddish and one blue glove. “A tough job,” she noted, “but in a beautiful place, connected with nature.” Her portrait recalls Richard Eberhart’s poem “The Clam Diggers and Diggers of Sea Worms” in which he pays tribute to their “dignity beyond speech.”

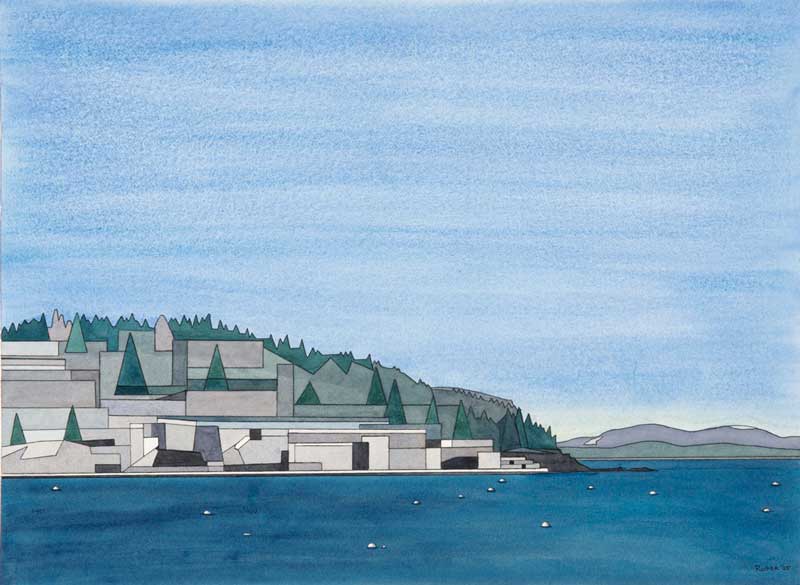

Bar Island in Winter began with a drive around Bar Harbor on a winter’s day. As she made her way around town, McDowell noticed the sun had finally grown strong enough to throw some “good shadows” on the island while the mooring balls stood out against a dark blue ocean. Snow and ice lent a chill to the landscape, with the faint outlines of Catherine and Caribou mountains visible in distant Franklin.

“Something catches my eye and I take a photo,” McDowell said. While she can paint from life, the light changes. At the same time, there are bugs and rain to tend with. Having dealt with some not-so-great photographs over the years, she has learned to pay attention to what she is feeling when taking the picture—and what she is looking at.

McDowell has favorite subjects, including the Asticou Azalea Gardens, which she paints nearly every year, and Little Long Pond. She also is an artist of animals—deer, bear, birds, etc.—each creature presented in striking geometric arrangements. And she has painted her share of vessels, from lobsterboats to schooners.

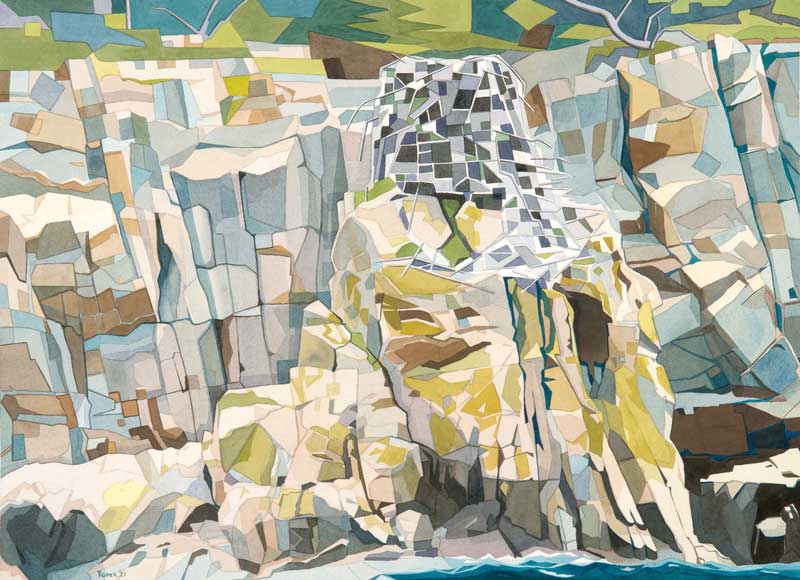

McDowell first used squares of color in a still life of flowers in 1973. She discovered she could move the viewer’s eye around the painting through patterns of shapes and colors. Today, using iPhone photos and sketches, she builds the overall outline and then works on the “insides.”

In a Facebook post, McDowell documented the making of a watercolor of the osprey nest on Sutton Island. The photographs show the incremental building of this well-known aerie in the Cranberry Isles. The progression of images reveals the essential abstract nature of the composition. In the end, the fractured planes somehow coalesce into this complex fish hawk home.

What attracts McDowell to watercolor? For one thing, she explained, it’s easy clean-up compared to oil. She used to work in both interchangeably, but found reeking turpentine fumes overwhelming, not to mention unhealthy. Over time, she has tweaked the watercolor technique to where she can manage the inevitable accidents that occur while working with the liquid medium.

Last summer, McDowell was one of 40 or so artists invited to paint on Hurricane Island in Penobscot Bay. Hosted by the Hurricane Island Center for Science and Leadership as part of its “Convergence: Art Meets Science” initiative, she relished the opportunity to explore the former quarry island—and help support this educational enterprise. Her watercolor of a coastal prospect displays her signature geometricizing of the view, a passing storm rendered as bands of gray, the straight lines calming.

Nomadic Beginnings

Born in the Jackson Heights neighborhood of Queens, New York, McDowell moved about as a youngster, first to Connecticut for a brief while, then to Princeton, New Jersey, where she attended Miss Mason’s School. While there, she met the famous cartoonist Walt Kelly, creator of Pogo. She got his autograph, which included a sketch of a puppy, which she proceeded to color in, much to the horror of her older brothers.

Around that time, the family started spending time in Maine, first staying in a cabin near Echo Lake on Mount Desert Island and then farther downeast in Milbridge. These early visits left their mark on McDowell and would draw her back to the area later on.

Norwich, Vermont, was the next stop, across the river from Dartmouth College. McDowell went to Marion Cross Grade School. Memories from that time include skating on Occom Pond and twice hearing Robert Frost recite his poetry.

Then in the early ’70s the family pulled up stakes once again to settle on Mount Desert Island where McDowell went through eighth grade then high school. “My mom was smart enough to move where there would probably be good schools for the kids,” she recalled. Her father’s work as a salesman led to the relocations.

McDowell’s mother didn’t believe in coloring books and so provided her daughter with art supplies, including those small watercolor sets with eight colors and a brush. “I went through so many of them as a kid,” she recalled. She spent a lot of time alone in her room painting, a habit she returned to when the pandemic struck.

The early encouragement led, in part, to McDowell signing her paintings “Roper,” her mother’s maiden name, when she got to college. She had started out using just her first name but stopped that practice after someone told her Vincent van Gogh had done that. She also chose the name because not knowing who Roper was meant that people would give an honest appraisal of her art. She still signs her paintings that way: “You do it long enough, you’re stuck with it,” she said with a laugh.

McDowell took three years off after high school, traveling to Florida in the winters to work and save money. While there, she took lessons in oil and watercolor at the Norton Gallery and School of Art three days a week.

McDowell recalled a memorable trip to Ireland in 1973. Her mother had come over on a boat in 1927, at age 15, and wanted to visit her homeland. Ireland was still at war at the time, and she remembered how the airport officials went through her luggage looking for American dollars, which could be used to purchase weapons. “I often tell people I was a product of a mixed Irish marriage,” she recounted, “because my father’s family were Episcopalians and Protestants from Northern Ireland and my mother was a Catholic from Southern Ireland—and neither family was happy about it.”

Returning to Maine, McDowell enrolled at the University of Maine, thinking she might get a degree in library science. Discovering it was a master’s level program, she switched to art. The department at that time was located in the university’s Carnegie Hall. She recalled an awkward basement space where you had to work around a post to finish a lithograph. As a work-study student, she did some secretarial work, including cataloguing materials on women in art.

McDowell took classes with Michael Lewis and Vincent Hartgen, both legends in the annals of that institution’s art department. Hartgen was especially memorable. She remembered how he would start an 8 a.m. art history class

by slamming the table and declaring,

“If I didn’t have Beethoven, I’d die.” McDowell credits Hartgen with teaching her about world history by connecting historical events to the art that was happening at the time.

McDowell’s pantheon of favorite painters includes Rockwell Kent, Edward Hopper, Picasso, Cézanne, Richard Estes, and Mondrian—“obviously” she said of the last-named, acknowledging the connection between the Dutch painter’s abstract-geometric compositions and her own. It is curious to note that the first painting to stop her in her tracks was van Gogh’s Starry Night, encountered during a stopover in Paris in 1973. “It was just like ‘boom’—I couldn’t move for like 10 minutes. I was just stuck there.”

By the Numbers

In 1978, McDowell and her husband, Terry Towne, purchased an “unfinished camp” overlooking Raccoon Cove in Lamoine. With no running water or electricity, they camped out to begin with, then slowly made renovations and additions. Today, it’s a lovely tidy two-story house, a retreat from the busyness of nearby Mount Desert Island.

While still at UMaine, McDowell began working for Acadia Corporation, which managed the Jordan Pond House on Mount Desert Island. Then president Ken Goodyear had her doing statistical reports related to sales and other aspects of the business. When the company’s bookkeeper left, Goodyear offered her the job. “I’m a blank slate,” she told him, but he assured her he could teach her. From then on, she was off and counting.

Along the way, McDowell worked for photographer Ed Elvidge in Southwest Harbor, doing design work and bookkeeping. She next took a job as comptroller at the Homestead Project, now known as KidsPeace, a residential treatment center for emotionally disturbed teenagers. When the organization closed, she moved to Downeast Horizons, which supports children with developmental disabilities. She worked there for six years.

When McDowell saw an ad for Friends of Acadia, she jumped at it. FOA’s mission focused on Acadia National Park, which is what had brought her family to Maine. She got the job and served as Director of Finance for the next 20 years, retiring in 2018.

While she sometimes found constant number-crunching trying, McDowell loved the FOA team and its mission—and is glad they are there today to support the park in light of the cutbacks to national parks. She praised former FOA president Ken Olson, who came up with the free Island Explorer bus idea.

Early on, McDowell showed her work at Rita Redfield’s gallery in Northeast Harbor. Redfield represented a strong stable of Maine artists, including Paul Black and James O’Neill. One of the paintings she displayed at Redfield’s didn’t make the cut: a remarkable image of two eagles, one of them holding a dead mallard. Based on an incident she witnessed out her window, the painting disturbed some gallery visitors. As McDowell learned watching Antiques Road Show, paintings featuring dead fowl don’t always appeal to collectors. That said, it is a remarkable painting.

Retirement has allowed McDowell to pursue her art with greater focus and determination. She continues to seek to improve her skills. This past August she took a three-day watercolor workshop with Mary Laury on Campobello Island. While she was taking notes on technique, her husband took a class with Chris Toy on Asian fusion cooking; both programs are part of an Acadian Arts Retreat offered by Maine Adult Education.

At one point during our interview, McDowell said, “Every day I feel lucky to live in Maine.” It’s a sentiment many of us feel in these stressful times. Her paintings help draw our attention elsewhere, to a world that is at once fragmented and full of life.

✮

Carl Little’s most recent books are the monograph John Moore: Portals and Blanket of the Night: Poems. He lives and writes on Mount Desert Island.

You can see more of Diana Roper McDowell’s work on her website, roperart.com. She shows with Artemis Gallery in Northeast Harbor and Burnt Coast Lighthouse on Swan’s Island.