Access to Swan Island in the Kennebec River is by boat only. Photograph by Greg Rössel.

Click on image to expand.

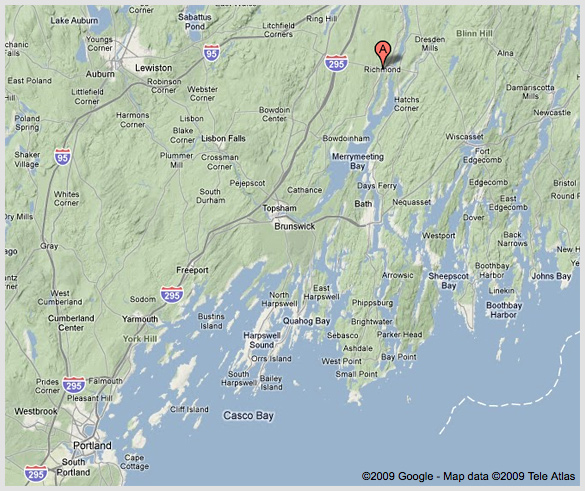

One is often tempted to search far afield to find remnants of the “Old Maine” pictured on tattered postcards with hand-canceled postmarks over one-penny stamps. Yet right here in central Maine, just a few miles south of the bustling state capital city of Augusta, in the middle of the Kennebec River, there is such a jewel—Swan Island.

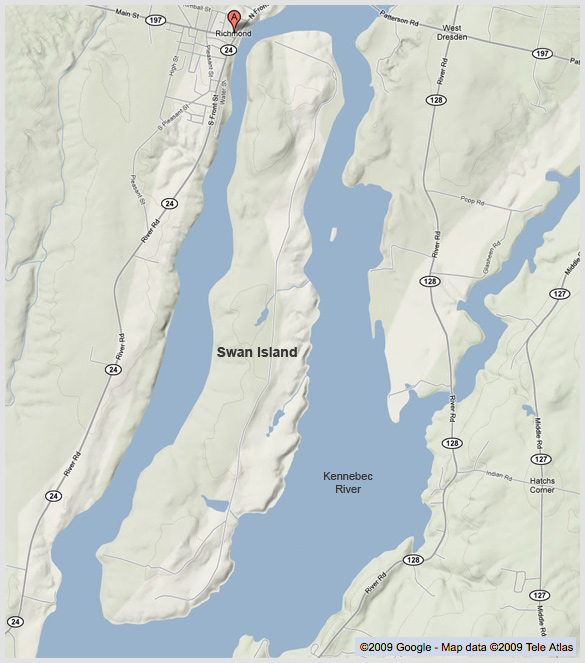

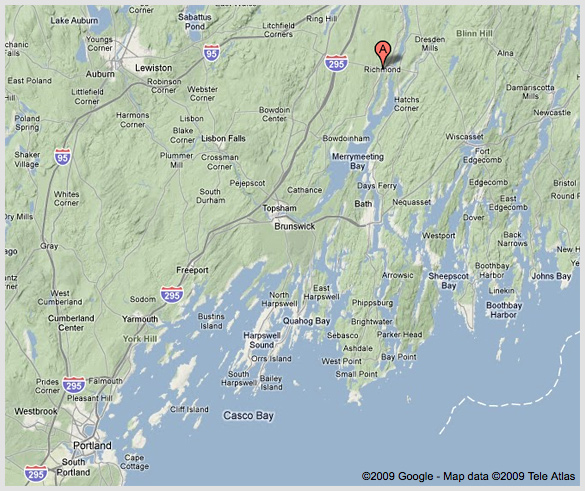

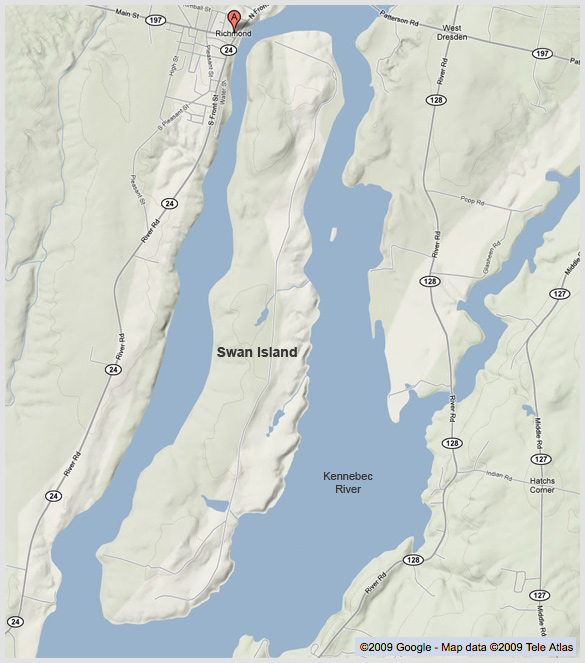

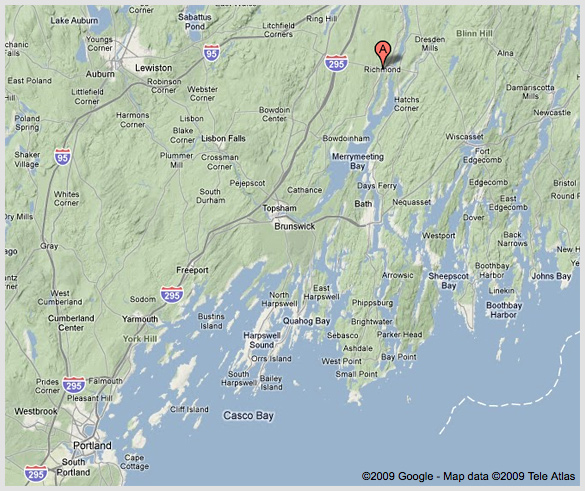

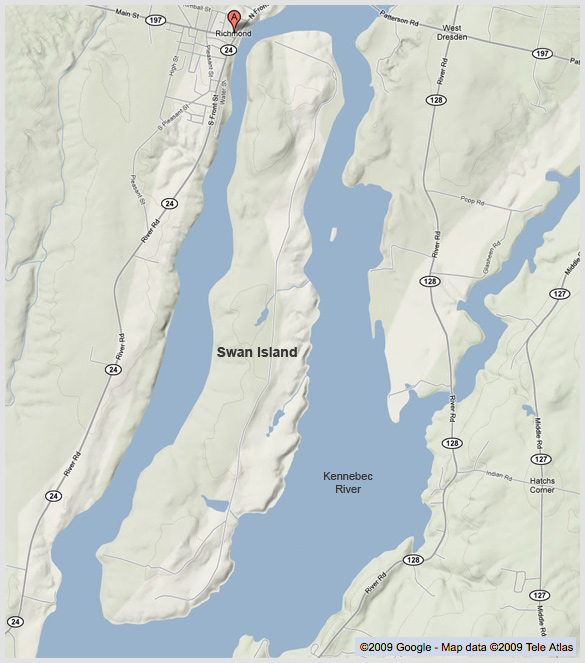

Situated just north of Merrymeeting Bay and mid-stream between Richmond and Dresden, lies a string-bean-shaped (4 mile x 3/4 mile) island and former township that is often confused with the better-known Swans Island in Blue Hill Bay. The riverine place is part of a 1,755-acre tract formally known as the Steve Powell Wildlife Management Area, which is comprised of two islands and several hundred acres of adjoining freshwater tidal flats, all managed the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife.

Swan Island has a long and rich historical significance—albeit one that is little-known in Maine. The earliest settlers were probably the Abenaki (a branch of the Kennebec tribe). It is thought that the island’s name was derived from a shortened version of the Abenaki name “Swango,” which means Island of Eagles. Others conjecture that the place was a stopping place for migrating swans (although there’s little evidence the fowl ever stopped there). At any rate, the first recorded visit of European settlers was in 1607 by members of the Popham Colony. The next was when Captain John Smith dropped in on the native inhabitants in 1614.

The first non-native homesteader showed up in 1730 and the island soon became the site of Indian attacks and abductions, tragic drownings, and the arrival of more settlers, and it played some bit parts in the Revolutionary War. Benedict Arnold’s expedition stopped on its way to attack Quebec and later, Arnold, Aaron Burr, and General Henry Dearborn spent a night resting on the island (where Burr allegedly met an Indian princess, Jacataqua, who then accompanied him to Canada and New York).

In 1847, after splitting from Dresden over a matter of taxes, Swan Island became the free-standing town of Perkins, well-situated to participate in the thriving economies of nineteenth century Maine. Shad fishing, farming, shipbuilding (at least seven sea-going ships were built here), a booming ice industry (the island boasted three major ice houses), and lumbering all prospered.

Photograph by Greg Rössel.

Click on image to expand.

By the turn of the century, however, all had changed. Iron and steel were the materials of choice for ship-building, plug-in refrigerators were all the rage, river pollution cut into fishing income and much of the forest formerly used for lumber had been converted to fields. So many inhabitants moved off island in search of work, that by 1918 there were too few to even fill the town’s elected offices and the town became Perkins Plantation. The Great Depression further encouraged the exodus of younger residents from the struggling farms in search of greener pastures and as in other Maine towns in that era, much land was lost to unpaid taxes. Probably the last straw was the 1936 discontinuation of regular ferry service from the island to Richmond and Dresden when a new bridge across the Kennebec was built just upriver. This effectively stranded the remainder of the island’s dwindling population.

The Maine Department of Inland Fish and Wildlife (IF&W) started purchasing land in the 1940s, primarily for migrating waterfowl production and management. Merrymeeting Bay was just to the south and the island, with its great wild-rice-producing mud flats, fields, woods, and potential pond sites provided an ideal haven for game such as duck, geese and other species. Using federal money, the state began purchasing the lands as they became available. In the process, Maine acquired a rural, agrarian, downeast version of a ghost town. Some might say the state got a good deal more than it had bargained for.

A good time (indeed, just about the only time) to visit Swan Island is from May 1 through Labor Day. Like its saltwater cousin, Isle au Haut, where there also are concerns about over-use, reservations are necessary. In season, an IF&W passenger ferry runs on a regular, as-needed basis from Richmond to the island. Alternatively, one can make the short journey via their own canoe. However one gets there, the effect is the same: crossing the short stretch of water transports one back to a slower Maine that existed 100 years ago. The paved road disappears, as do all except the island’s service vehicles. Instead there is but a single dirt lane that travels the length of the island, wending its way past the remaining eighteenth and nineteenth century homes and cellar holes, past the corn crib and the cemetery, and past ponds, woods and high rolling fields that continue down to the tidal Kennebec.

As a preserve, the place is extraordinary. The environs have been managed to provide a good living for great variety of species including sturgeon, bald eagle, blue heron, white-tailed deer, wild turkey and monarch butterflies. The former Frye Mountain fire tower was moved to a high island field in 2003 to be used for wildlife spotting. Perhaps equally remarkable is the size of the trees. The ancient farm and roadside trees have been allow to grow to a scale not usually seen in Central Maine including grand white oaks that are a rarity this far north. In the campground (more on this in a bit) there is a specimen that is reminiscent of the Charter Oak emblazoned on the commemorative Connecticut quarter dollar.

To give the visitor a feel for the place, the island staff offers a guided tour aboard an open-stake bodied truck. But with that under your belt, pack a lunch and a camera into a day pack, don some good walking shoes and get out on the road and nature trail system that take you out into the smells of the sweet fern and forest. For those who can stay longer, camping is the way to go. The island has 10 log Adirondack shelters placed at the margins of an eighteenth century field that overlooks the homestead, Little Swan Island, and the eastern channel of the Kennebec. It is here, especially, after the day-visitors leave, that one can feel they have wandered back into another time. Surrounded by preserved land and with no modern dwellings, sounds, or lights visible at night, the place seems as remote as Chesuncook or Baxter. If one is fortunate to have a canoe, the campground is an excellent base to explore the ever-changing tidal river, shore and flats.

Getting back to the buildings: during its heyday, the community hosted at least 27 houses -- six of which still exist -- including a 1763 colonial saltbox and a square, ca.1800 Federal-period house complete with stenciled floor and a Dutch oven. For the IF&W, the presence of these structures is a double-edged sword. With its many historic sites, the island has been justifiably added to the National Register of Historic Places in its entirety. The question then is who is responsible for taking care of all of these great empty buildings exposed to the full range of Maine’s climate. It can be argued that cultural and historical preservation (not to mention campground management) is a bit of a stretch from the core job description of the IF&W.

Yet, Swan Island is a special case and Charles “Rusty” Dyke, the island’s longtime wildlife biologist and manager is well aware of the dilemma. Says Dyke “The island’s mission is multi-function: wildlife management, historical, interpretive, and camping. It’s both a balancing act and a challenge” A challenge indeed. Not only do Dyke and his two part-time staff have to perform their usual scientific tasks, oversee the structures, and interpret the island to visitors, they also have to essentially run a town: cutting the fields every one to three years, repairing roads, and maintaining boats, docks, and vehicles. All this is done on a shoestring budget - $80,000 is the annual operations cost to cover everything. Notes Rusty Dyke, “It is difficult to get all the work done.”

Perhaps surprisingly, right now there are no regular dedicated state funds to maintain this special place and its inherited un-funded liabilities. And, as the island’s mandate is primarily for promoting the good of wildlife, Dyke cannot simply turn the place into a theme park to get the numbers up at the gate. “We can’t have a hundred thousand (visitors) come through here,” he said.

This has led to creative partnerships to attempt to bridge the gap. In 2001, Friends of Swan Island, a private non-profit volunteer group, was organized to preserve Swan Island and rehabilitate the remaining six historic homesteads. The “Swan Island Project,” linked with the Richmond schools, has also been restoring one of the island’s homes. That said, with a bit of support, this island in time could become an educational center for both living history and wild life conservation. Indeed, there are few places in central Maine so unusual and worthy of preservation, supporting and visiting. And why not bring a friend or state legislator with you when you go?

Swan Island road traverses the island from end to end.

Access to Swan Island in the Kennebec River is by boat only. Photograph by Greg Rössel.

Access to Swan Island in the Kennebec River is by boat only. Photograph by Greg Rössel.

Swan Island road traverses the island from end to end.

Swan Island road traverses the island from end to end.

Access to Swan Island in the Kennebec River is by boat only. Photograph by Greg Rössel.

Access to Swan Island in the Kennebec River is by boat only. Photograph by Greg Rössel.

Swan Island road traverses the island from end to end.

Swan Island road traverses the island from end to end.