In these uncertain times, I look back now on my childhood summers through the dreamy lens of nostalgia. But the way these past few years have narrowed and stilled my life reminds me that there was a time when, at least in the summer, simplicity sustained us. We cherished laughter and silliness; we learned the art of conversation; we ignored clocks except to keep track of the tides.

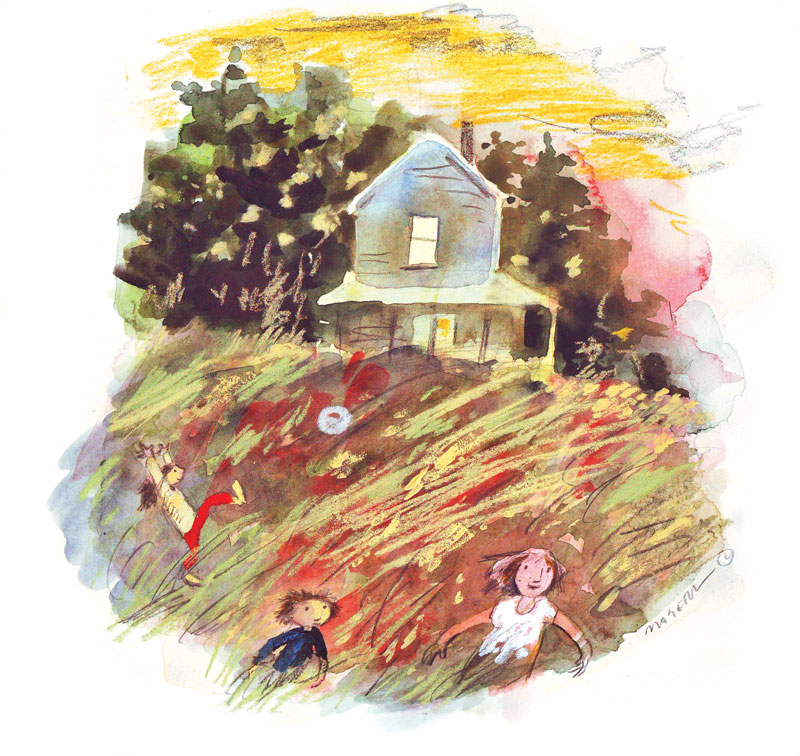

Every summer night after dinner, the kids on Hurricane Ridge gathered at the field to play Kick the Can and Capture the Flag. We played until dark—so dark that we could simply lie in the grass and not be seen. As night settled in, our parents would clang the porch bell to call us home.

Illustration by Caroline Magerl

Illustration by Caroline Magerl

Our nightly neighborhood games were both entertainment and ritual, rooted in an interesting mix of spontaneity and routine. Imagination and playfulness ruled. Simple pleasures sustained us: swimming to Miss Pinkham’s Island; playing fort in the pilings of the town dock; investigating tide pools at the point; gathering berries on Haskell Island. While there were certain routines to our days—jumping off Ronnie’s wharf could only happen at high tide—we enjoyed an unstructured and unfettered life in the summer. We rarely suffered from boredom; even when the fog set in, there were books to read, board games to play, and penny candies to eat.

One of our favorite summer games was recreating The Man from U.N.C.L.E. in elaborate skits, complete with imaginary props, as we combated our archenemy THRUSH. And, of course, we all had tiny transistor radios that we carried with us to keep up with The British Invasion. Somehow, even with our love of popular culture, we did just fine on this tiny spit of land for three months of the year. Our cottage had no well (a cistern collected rain water), no insulation or heat other than a fireplace, no modern conveniences. We lived by Thoreau’s adage: “Simplify, simplify.”

We loved ghost stories, a staple of the many sleepovers and sleep outs we held during our summer stays at our cottage. Before we turned our garage into a bunkhouse and had the luxury of mattresses to sleep on and a roof over our heads during rainstorms, we slept out in homemade tents. Army blankets draped over clotheslines and anchored at the top with wooden clothespins and at the bottom with large rocks from the beach became makeshift shelters where neighborhood kids gathered to stay up late and to laugh and shriek at ghost stories.

Another summer staple was penny candy: candy buttons, Atomic fireballs, Mint Julep chews, Pixy Stix, Sweetarts, Chiclets gum, Smarties, Sugar Daddy suckers, Tootsie Pops, root beer barrels, string licorice, Mary Janes, Necco wafers, wax lips. We purchased our candy from Highway Market 123, the small country store next to the town dock. To pay for our bags of penny candy, we scoured the ridge for empty Coca-Cola bottles to return for refund or, if we were feeling particularly lazy, we snuck pennies and nickels from the change jar kept on the corner of the dining room cupboard.

Decades later, I still cherish time at our family cottage—roasting marshmallows in the fire built from driftwood twigs from the beach; dressing up with wigs and costume jewelry; walking on handmade stilts; swinging in the hammock; walking barefoot; telling stories over leisurely dinners; watching fireworks illuminate Casco Bay on July 4th.

As our lives get more complicated, and more bound to technology, finding the way back to that childhood sense of wonder at a summer cottage reminds us of what is possible.

Every May, I arrive to open and clean the cottage, a ritual that reminds me of our family’s long history here. Sometimes the cistern is empty, so I use the hand pump across the street to haul water to clean the cottage. I think of the generations of women who came before me to open up cottages, opening doors and windows to air out the mustiness of a long winter, filling ice chests. My mother used to open the cottage each spring. Until I took over this task after her death in 1995, I had no idea how much work it entailed.

Some folks who came in the Victorian heyday of summer vacations would have arrived after journeys that began in Boston or Portland and ended at the town landing in South Harpswell where the steamer Merriconeag would deliver them. They would have stayed at one of the many hotels or guesthouses that once prospered here: Merriconeag House, Harpswell House, Hotel Germania. But by the time my parents purchased our cottage on Hurricane Ridge in the early sixties, the hotels were long gone. The stories of those earlier times, however, survived—such as the legend that the last sighting of The Dead Ship of Harpswell was observed by a guest staying at Harpswell House. Whenever we took a walk to Pott’s Point, my father would point out the spot where this hotel once stood and I would imagine what it would have been like to have worn a long hoop skirt and to have had afternoon tea on the porch and see a ghost ship.

One beautiful summer day when I was quite young, my father suggested that we take a walk to the point for a picnic. He grabbed a couple of bananas, a can of sardines, and a jar of peanut butter, and off we trotted. Our path took us past Cliff Moody’s lobster shed, past the site of the long-gone Harpswell House, past the sagging apple tree with a wooden bench where I sat to rest my little legs. When we reached the point, we crawled atop the rocky ledges and my father pointed out the flag waving to us from the tiny island across the sound, a sign that Miss Pinkham was in residence. On the return trip, when my legs became tired, my father hoisted me to his shoulders and carried me the rest of the way home, past the cottages on the point, past the apple tree, past the field where the Harpswell House once stood, past whatever ghosts may have been lurking in the shadows.

My father died suddenly of a heart attack in October 1984, and his ashes were scattered off the point. I have often wondered, especially in these recent strange and unsettled years, what he would have had to say about the challenges and upheavals we have witnessed since his death. I like to imagine his spirit living on in the seagulls that greet me now each time I walk to the end of Pott’s Point and place my feet atop the geodetic survey marker embedded in the ledge there at the edge of land and sea.

One of the greatest joys of spending time at our cottage for over half a century has been watching my now-grown daughter’s attachment to this place. She understands how fortunate she is to spend time here; she understands that returning each summer connects her to a family history that traces back three generations; she understands the great gift of life-long friendships. Photos on the walls, memorabilia throughout the cottage, and my father’s Harpswell Notes journal he kept each summer all speak of the lives of my parents. Their legacy lives on, in their children and grandchildren, in this magical cottage, in the stories we tell.

And so, each summer, the spirits of the past greet us as we arrive at our cottage. As my father often said, “Ain’t we lucky?”

✮

Martha Andrews Donovan teaches and writes at the edge of land and sea on Mount Desert Island, where she lives when she’s away from Harpswell.