This article is part of a series in our Special Report on Aquaculture in Maine. Continue reading the rest of this series at the end of this article.

Once upon a time, there was a thriving commercial fishery for Atlantic salmon in Maine. In the spring, when the fish ran up Maine’s rivers to spawn, they were caught by the tens of thousands and rushed to distant city markets. Penobscot salmon was most celebrated and cited as such on fancy restaurant menus. “Penobscot salmon are the best,” noted Fannie Merritt Farmer in her 1918 Boston Cooking School Cookbook. (Then she sort of blew it, by adding that they “come from Maine and St. John, New Brunswick.”)

Nowadays, fish biologists are overjoyed when a mere 1,000 salmon return to the Penobscot in a season. Since 1948, the commercial fishery has been non-existent and it’s prohibited to fish for or to consume Atlantic salmon. But Maine salmon is still a prized fish, entirely farmed and entirely by one company, the Canadian firm, Cooke Aquaculture, which is based in New Brunswick, but has farms all over the world, including Scotland, Chile, and Washington state. In Maine, Cooke leases 24 ocean-pen sites between Bass Harbor Light on Mount Desert and Eastport, plus three inland hatcheries where smolts are raised to stock the ocean pens.

The early story of salmon farming in Maine is a contentious one, especially in Cobscook Bay where the first commercial salmon farms were located.

With its robust tides that flood and flush regularly with cold, nutrient-dense ocean water, Cobscook was targeted as an ideal site back when the Norwegian idea of ocean pens for raising salmon first took hold on this side of the ocean. But a lot of mistakes were made, and not just in Maine, in what was in essence a start-up industry. As salmon farms struggled and failed, Cooke began to buy up leases and consolidate them. By the first years of the present century, Cooke was the leader in salmon farming in Maine, a situation that continues to this day.

But salmon farming today is a far different enterprise from what it was back in those early years. A lot of the credit for that must go jointly to Maine’s Department of Marine Resources and Cooke, working together to develop protocols for a safe, sustainable, and economically viable salmon industry. Maine’s stringent environmental guidelines require regular year-long fallowing of net pens after harvest, reducing the impact on the benthic environment, as well as strict controls on the use of pesticides, fungicides, and medications, aspects of salmon aquaculture that have been censured in the past. Antibiotics, for instance, can only be used to combat actual disease (i.e., not to promote growth) and must be approved and closely monitored by both state and company veterinarians. No salmon with a trace of antibiotics in its system can be sent to market. Moreover, Maine law specifically forbids the introduction of genetically modified salmon (a.k.a. Frankenfish) anywhere in the state.

The methods used today to bring fish to full market maturity have evolved a great deal. Fish swim freely in pens without overcrowding, and the feed is closely monitored so that there is a minimum of excess beyond what the fish consume. Even the issue of how much wild fish is needed to produce a pound of farmed has been addressed, with the ratio dropping from an original five-to-one, wild to farmed ratio, to the current 0.6-to-one—in other words, it takes around nine ounces of wild fish to produce a pound of farmed. It should be noted that industrially produced pork and chicken consume by far most of that wild-fish-derived feed.

There is a huge market for salmon in the United States. Consumers like the delicious, easy-to-cook fish that is regularly touted for its healthful quotient of Omega-3 fatty acids. In fact, it’s America’s third favorite seafood, after shrimp (mostly imported) and tuna (mostly canned), as Americans consume far more seafood today than ever before.

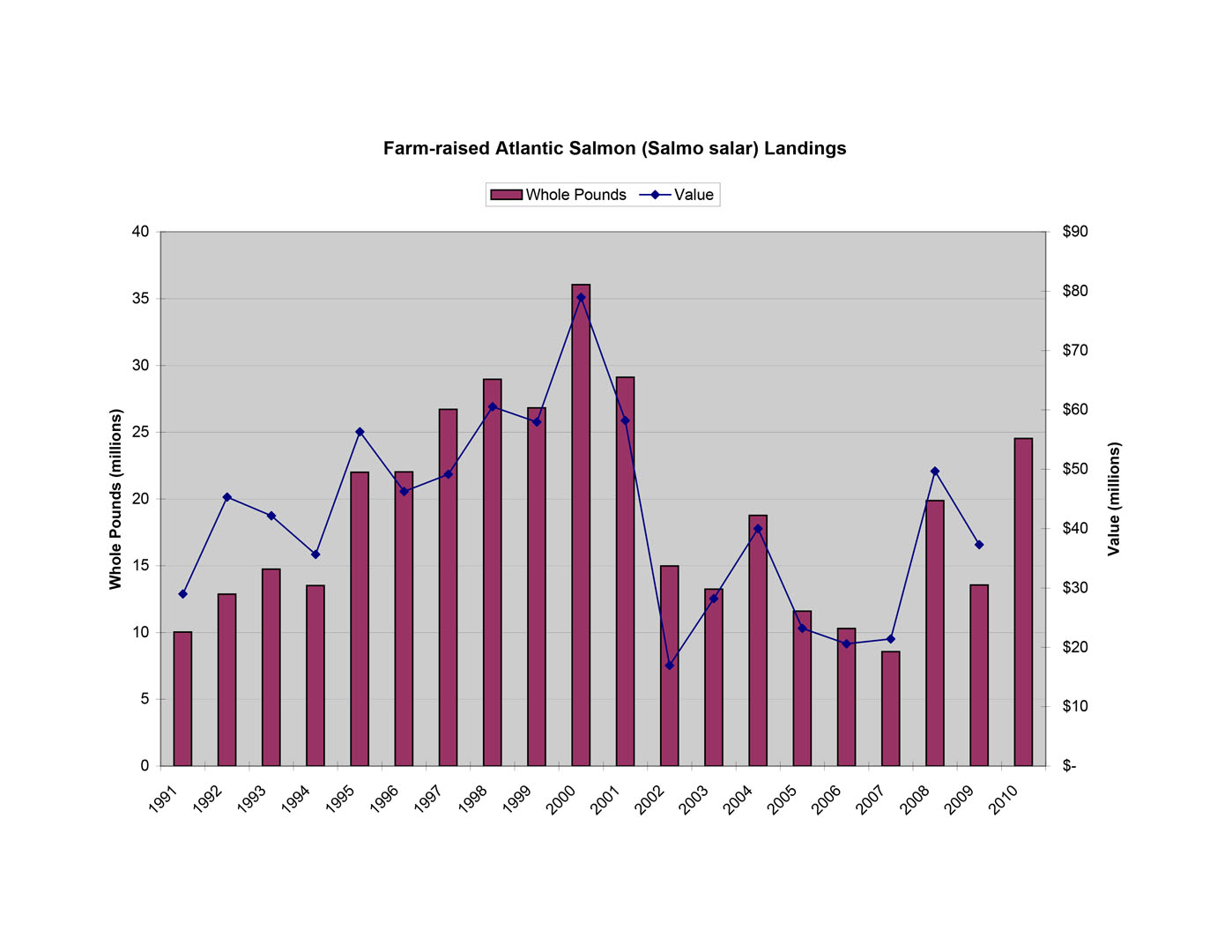

Still, a vast quantity of the Atlantic salmon we eat is imported, from Norway, the British Isles, or Chile. True North, the brand under which Cooke markets their Maine salmon, is “a drop in the bucket,” according to Andrew Lively, True North’s director of public affairs. In 2018, Americans consumed more than 450 thousand metric tons of Atlantic salmon, of which Maine produces, according to Lively, “only a small single-digit percentage.” The rest is all imported.

Still, a vast quantity of the Atlantic salmon we eat is imported, from Norway, the British Isles, or Chile. True North, the brand under which Cooke markets their Maine salmon, is “a drop in the bucket,” according to Andrew Lively, True North’s director of public affairs. In 2018, Americans consumed more than 450 thousand metric tons of Atlantic salmon, of which Maine produces, according to Lively, “only a small single-digit percentage.” The rest is all imported.

There are still plenty of vociferous opponents of salmon farming in Maine, despite the progress in methods. Those voices may never go away. One of the most contentious claims is that farmed fish are detrimental to the survival of threatened wild salmon, passing on diseases and competing with wild salmon for food. But the Atlantic Salmon Federation, the major international organization that works to protect wild Atlantic salmon populations, has praised Maine’s salmon regulation efforts as an example that all salmon farmers should follow. Not only that, but the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Watch program, which keeps rigorous tallies on sustainable seafood harvesting around the world, has given a yellow light to Maine-raised salmon. That’s not quite a green light but it’s the next best thing.

Aquaculture, on the whole, has the least environmental impact of any other form of protein production, according to many authorities, but especially a lengthy comparison compiled in 2018 by the World Economic Forum (https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2018/06/these-meat-and-fish-choices-hurt-the-environment-most/).

Maine’s standards are coherent and sustainable. Yes, there was a time when salmon aquaculture especially was noted for some bad practices, including overcrowding of pens and the use of growth stimulants and fungicides to protect the fish. That is in the past and while there may still be salmon farms in the world that do a terrible job, Maine farms these days are considered to be in the forefront of wise practices.

In the meantime, Cooke is playing a major role in a unique program to increase the population of wild salmon in the Penobscot River. In the past, salmon smolts were released from hatcheries with the expectation that they would take up a more or less normal salmon life cycle. But enormous, uncountable numbers of those fish utterly failed to survive. Now, working with the Department of Marine Resources and the Penobscot Nation, Cooke is raising these baby salmon in net pens to full-scale adults, ready to spawn, at which point they will be released in the East Branch of the Penobscot. The idea is that more salmon may survive to spawning stage, releasing more eggs in the redds (salmon nests), and those eggs will grow to adults with the river imprinted in their DNA. The hope is that this will lead to an increase in salmon populations in the Penobscot, and eventually other rivers. That effort, coupled with the breaching of dams on the Penobscot, the Kennebec, and other major salmon rivers, might—just might—mean that our grandchildren and their grandchildren will be able to enjoy the pleasures that once delighted our great-grandparents. It’s a long shot, but it might work.