Youthful Adventures in Maine Antiquing

Twelve-year-old Earle G. Shettleworth Jr. displays his antique telephones and Edison phonograph in 1961. Photo from the author’s collection

Twelve-year-old Earle G. Shettleworth Jr. displays his antique telephones and Edison phonograph in 1961. Photo from the author’s collection

There is an adage in the world of antiques that New England is the attic of America, and that, in turn, Maine is the attic of New England. I learned the truth of this saying at an early age in the 1950s and ’60s. As the result of a precocious interest in history and a passion to experience it through tangible artifacts, I made my first foray into an antique shop in the summer of 1955 when I was 6 years old.

Returning from a family trip to Quebec City, I begged my parents to stop at a shop on the main street of Bingham, which I had spotted on our way to Canada. A friendly middle-aged couple, Barbara and Maurice Alkins, presided over neatly arranged aisles of glass, china, lamps, clocks, and furniture, along with picture-covered walls and an adjacent barn full of larger items.

The fascinating world of objects that the Alkins had created within their store would draw me back to Bingham many times over the coming years. But on that first visit, I focused my attention on a print of Gilbert Stuart’s Athenaeum portrait of George Washington in a rustic Victorian frame. Naively believing that I may have discovered an original painting, I told my parents that this was the one present I wanted for my seventh birthday, regardless of the price.

The days to August 17th passed quickly, and that morning I was driven to Bingham to secure my Washington portrait for all of $2. Time would prove it to have been clipped from a 1932 Washington Bicentennial calendar, but I prize it to this day.

It was in the building on Main Street in Bingham, which housed Barbara and Maurice Alkins’ antique shop, that the author got his first taste of historical images. Maine Historic Preservation Commission

It was in the building on Main Street in Bingham, which housed Barbara and Maurice Alkins’ antique shop, that the author got his first taste of historical images. Maine Historic Preservation Commission

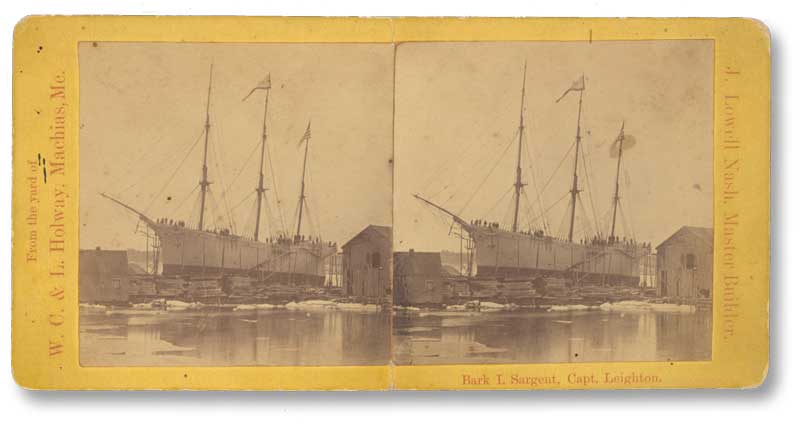

At the Alkins’s shop, I first learned about historical photography by finding a large carton of stereo views priced at a dime apiece. When Maurice cleaned out a house, he would deposit what views he found in this box at the back of the store. Suddenly, I was confronted with hundreds of 19th century images of Maine cities and towns, the Civil War, Western settlement, and the far corners of the globe. The Maine cards found in that carton formed the basis for what is today the Maine Historic Preservation Commission’s collection of 20,000 stereo views of the state.

The Western views provided me with my first lesson in capitalism. Purchasing William H. Jackson views of Colorado and Edward Muybridge views of California for 10 cents each, I sold them for a dollar apiece to collectors who advertised in the Antique Trader newspaper. The profit margin seemed wonderful at the time, but some of those images of Colorado mining towns and Victorian San Francisco by noted Western photographers such as Jackson and Muybridge are now worth hundreds of dollars.

As my interest in collecting grew, my parents and I explored many of the shops in Central Maine during the summer months we spent at our cottage near Skowhegan. One of the highlights of each season’s rounds was the shop run by Barbara and William Kenniston in an old schoolhouse in Pittsfield, on the route between Skowhegan and Bangor.

As a boy, the author often began his tour of Portland’s shops at the Cinamon Building, on the corner Pleasant and Center streets, the location of Sam Cinamon’s antique and used furniture business. Portland Room, Portland Public Library

As a boy, the author often began his tour of Portland’s shops at the Cinamon Building, on the corner Pleasant and Center streets, the location of Sam Cinamon’s antique and used furniture business. Portland Room, Portland Public Library

In the high-ceilinged main room, the Kennistons attractively displayed hundreds of choice pieces of glass and china on shelves located in front of multipaned windows, while the walls were covered with prints and paintings. A smaller room at the rear overflowed with clocks, furniture, and more pictures. From behind a counter in the main room, Mrs. Kenniston dispensed stereo views, postcards, photographs, and highly informative conversation that reflected a deep interest in her work. She and my mother enjoyed long talks together, and on one occasion Barbara shared a personal treasure with us, a collection of vividly written Civil War letters by Corporal Hiram Roscoe Brackett from Detroit, Maine. Because Barbara kept these prized manuscripts in a chest of drawers near the counter, my mother always referred to the Brackett letters as “courage from an old bureau drawer.”

In front of their shop, the Kennistons maintained a display of larger objects to attract passing motorists, including a rack of porcelain chamber pots. One afternoon a young couple from New Jersey enthusiastically purchased a large, flowered chamber pot for $25, with the expressed intention of using it to serve spaghetti and meat balls, apparently innocent of the object’s original purpose.

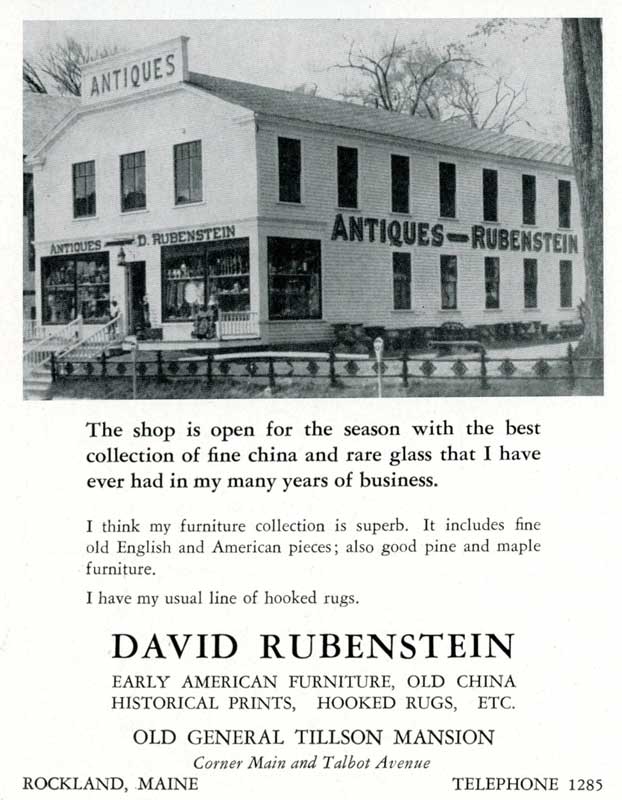

My early antiquing experiences were not confined to Central Maine. Family trips to the coast included stops at David Rubenstein’s famed shop housed in a large two-story building on Main Street in Rockland. Rubenstein specialized in furniture, china, glass, and hooked rugs.

On my first trip to Mount Desert, I explored the many rooms of P.P. Hill’s shop in Northeast Harbor, which claimed to have the largest collection of antique clocks in the state.

When I accompanied my father on business trips to Boston, we would visit the old bookshops in Scollay Square. While visiting relatives in Connecticut, I spent a morning at Norman Flayderman’s store in Greenwich, a veritable museum of historical military items. There I purchased several original issues of Harper’s Weekly, illustrated with wood engravings of the Civil War.

What started as a summer recreation soon became a year-round pursuit. Before long I was haunting the antique shops of my native Portland. This began at the age of 12, in 1960. I would take the bus into the city and start my rounds at Sam Cinamon’s four-story brick block on the corner of Pleasant and Center streets. A native of Russian Poland, Sam had arrived in Portland in 1904 at the age of 11, and five years later joined his uncle’s second-hand business. In 1925 he opened his own antique and used furniture store on Fore Street, later moving to the large building at Gorham’s Corner that still bears his name.

Cinamon was a small, energetic man with an outgoing personality and a twinkle in his eye. Both he and his pleasant wife, Mamie, who frequently spent the day with him at the shop, were always well dressed and attentive to customers amid a profusion of merchandise that filled four floors of what had been a cold-water Irish tenement. He had known members of my mother’s family, including my grandfather, and he always found time to talk with me as well as to sell me whatever old photographs of Portland I found at a bargain price of $1 apiece. These included the earliest known photograph of Portland Head Light, dating from 1858.

Sam Cinamon handled many Portland estates during his decades in business, from which came notable furnishings and paintings. One of his most devoted customers was Judge Arthur Chapman of Cape Elizabeth, who once purchased a Fitz Henry Lane marine painting from Cinamon for $50. When Judge Chapman’s estate was auctioned in the 1960s, the sale of the Lane for $10,000 electrified the Maine antique market. Today that picture would bring at least a million dollars.

A short walk from Cinamon’s brought me to F.O. Bailey, located in a hip-roofed brick Federal house at Free and South streets. The Fox House was one of the last remnants of the fashionable Free Street neighborhood, and it provided an appropriate setting for the city’s oldest auction firm.

Sam Cinamon collected many of his treasures while handling estates in Portland. Portland Room, Portland Public Library

Sam Cinamon collected many of his treasures while handling estates in Portland. Portland Room, Portland Public Library

Founded in 1819, Bailey’s had been purchased by the Allen family in the late 19th century and had been run by Neal Allen Sr. since 1912. Like Sam Cinamon, Allen knew members of my family; and when I started to frequent Bailey’s, he treated me graciously. A tall, distinguished-looking man in his 70s, he conducted himself in a warm and courtly manner. His well-ordered, first-floor showroom displayed the best in glass, china, furniture, and paintings that Portland had to offer, its appearance being reminiscent of the better Charles Street shops in Boston. Less organized but equally intriguing were the second-floor rooms and the huge adjacent warehouse on South Street.

Allen and his staff, which included his son Franklin Allen, were indulgent of my interest in Portland history and sold me local photographs and ephemera for modest prices. At one point Neal Allen priced a fine lithograph of Abraham Lincoln for me at $5, and another time he allowed me to buy a $30 Currier and Ives print in $5 installments.

The author still has a 1954 advertisement for David Rubenstein’s antique shop, on Main Street in Rockland. From the author’s collection

As a summer reporter for the Portland Press Herald, I covered Bailey’s three-day auction of the Kenneth Roberts estate in Kennebunkport in July 1967. By then 82 years old, Neal Allen opened the sale to a round of applause. Terming the sale the most perfect of his long career, he auctioned the first 11 items of pewter before turning the gavel over to his son Franklin.

The author still has a 1954 advertisement for David Rubenstein’s antique shop, on Main Street in Rockland. From the author’s collection

As a summer reporter for the Portland Press Herald, I covered Bailey’s three-day auction of the Kenneth Roberts estate in Kennebunkport in July 1967. By then 82 years old, Neal Allen opened the sale to a round of applause. Terming the sale the most perfect of his long career, he auctioned the first 11 items of pewter before turning the gavel over to his son Franklin.

From F.O. Bailey, I went to the Century House at York and Brackett street, near the Million Dollar Bridge between Portland and South Portland. This weathered red cape was home to Pearl Pyne’s antique shop. An interior as time-worm as the exterior provided the setting for an eclectic array of objects. Pyne, was a thin, wispy figure who contributed to an atmosphere that was straight out of a Dickens novel.

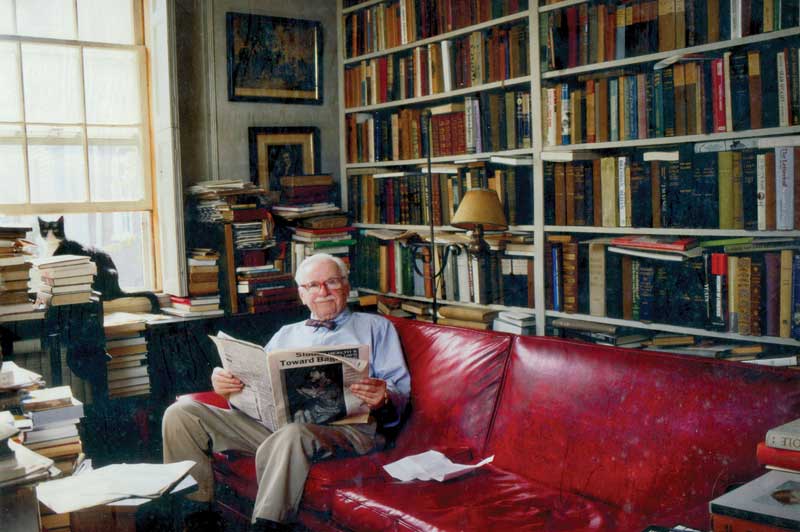

By late morning, I arrived at 38 High Street, the home and shop of Francis M. O’Brien, Maine’s leading antiquarian bookseller. O’Brien had been dealing in books, manuscripts, prints, and ephemera since 1934. By the 1960s, he was recognized as one of the most knowledgeable and respected bookmen in America. Each visit to the old brick house on High Street held the dual promise of finding an item for my collection and conversing with one of the state’s most engaging intellects.

After a sandwich and an ice cream soda at W.T. Grant’s lunch counter, Bentley’s Restaurant, or Moustakis’s Soda Fountain, I completed my Saturday tour at the Portland Street shop of Ruth Boyd. In many respects, Boyd was the most colorful Portland antique dealer of her time. Born in St. John, New Brunswick, she came to the city at the age of 5 in 1902 and graduated from Portland High School in 1917. Her maiden name was Gibson, and she had cut an attractive figure in her youth, resulting in the accolade of “Gibson girl” after the artist Charles Dana Gibson’s popular depictions of American beauties.

Ruth Boyd was a colorful and memorable character in the Portland business community. Portland Room, Portland Public Library

Ruth Boyd was a colorful and memorable character in the Portland business community. Portland Room, Portland Public Library

During the 1920s, Boyd’s outgoing personality and good looks earned her a place in official greeting parties for famous people visiting the city, and she cultivated these contacts when she opened Longfellow Antiques at 86 Portland St. in 1933. She made sales and sent gifts of antiques to presidents, governors, military leaders, and show business personalities, whose inscribed photographs and thank you letters were scattered throughout the store.

Boyd’s specialties were lamps and postcards, and her shop as well as her vintage station wagon were packed with both. Navigating Longfellow Antiques was accomplished through narrow paths shoulder high in accumulations that would have made the famed New York hoarders, the Collyer brothers, feel at home. My destination in this chaos was the numerous boxes of postcards on the shelves that lined the walls. From these bins, for a nickel a piece, I began a collection of Maine postcards which now comprises thousands of architectural images of houses, buildings, and street scenes.

Books were front stage at the Portland shop run by Francis M. O'Brien. From the author’s collection

Books were front stage at the Portland shop run by Francis M. O'Brien. From the author’s collection

Boyd worked tenaciously at her trade well into old age, dying in 1996 at 99. Her morning routine consisted of a visit to the Salvation Army, Goodwill, and any house or yard sales listed in the papers. Promptly at 1 o’clock, she opened her shop for four hours of afternoon business, sitting on the stoop in the warmer months and in her heated station wagon during the winter because there was no room left for her in her store.

She took a direct marketing approach with her established customers. For example, if she found a good piece of pewter, she would bring it straight to the Portland collector Dr. William A. Monkhouse while he was having lunch at the Hospital Pharmacy. Transactions were concluded on the spot.

And Boyd had the last word for those who might look askance at her appearance, her shop, or her car as the decades began to take their toll. One day she overheard a man in the Miss Portland Diner on Marginal Way point her out as “the old lady who runs the junk shop,” and she turned to him and snapped, “Yes, and I’m the old lady who goes to the bank every day.”

The antique business remains an integral part of Maine’s identity. The state’s image as a source for antiques is reflected in the monthly issues of the Maine Antique Digest, which Samuel Pennington of Waldoboro founded in 1973. Each year shops, antiques shows, and auctions confirm that the attic of New England still offers its treasures.

✮

A Portland native, Earle G. Shettleworth Jr. directed the Maine Historic Preservation Commission from 1976 to 2015 and has served as the Maine State Historian since 2004.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.