Rachel Carson explores the fine details of the beach by her house in Southport, Maine, with a young friend in 1961, about a year before her ground-breaking book Silent Spring was published. According to a recent Carson biography this photo was one several taken by Erich Hartmann of Magnum Photos for the John Hopkins University alumni magazine for a special issue on the ocean. Erich Hartmann / Magnum Photos

Rachel Carson explores the fine details of the beach by her house in Southport, Maine, with a young friend in 1961, about a year before her ground-breaking book Silent Spring was published. According to a recent Carson biography this photo was one several taken by Erich Hartmann of Magnum Photos for the John Hopkins University alumni magazine for a special issue on the ocean. Erich Hartmann / Magnum Photos

When the tide falls on the Sheepscot River, a new world appears again, a place of tide pools, mats of rockweed flattened over craggy ledges, clumps of marsh grass, windthrown beaches of shell and sea glass. The setting sun casts beams of pink and gold light on the river as a great blue heron glides in and lands on a rock, surrounded by water and reflected by its liquid mirror.

To a girl who grew up reading poetry and playing in Allegheny streams, a storyteller who dreamed of the sea before she ever saw it, a biologist who studied between world wars and took a job with the federal government to support her family, this tiny sliver of the Maine coastline must have seemed the strangest and most familiar place in the whole world.

In this 1961 view, Rachel Carson looks for marine life under the seaweed near her house in Southport. Image courtesy Erich Hartmann / Magnum Photos

In this 1961 view, Rachel Carson looks for marine life under the seaweed near her house in Southport. Image courtesy Erich Hartmann / Magnum Photos

Since 1935, Rachel Carson had been working as a science writer for the U.S. Department of the Interior. She edited manuscripts, managed a library, wrote speeches and radio scripts, prepared congressional testimony, and worked to make government information about fisheries and wildlife more interesting and appealing.

She had a nearly blank slate and plenty of fodder—oceanography had yet to emerge as a discipline but scientists had numerous studies of fish and shellfish under way. She loved to go out in the field with them, to see marine life first-hand and understand the context for her writing. In the field, she also felt nature’s powerful influence on human emotions. The visceral was vital to her work.

Picture her: She stands knee-deep in a stream of mullet racing the outgoing tide, so overwhelmed with the force and beauty of the fish she is crying, her tears mixing with the darting, silvery bits of life flowing by her feet in their race to the sea. She is crouched on the deck of a rocking ship, sorting through animals dredged from the ocean floor, in awe of their varied shapes and textures as waves slap the bow. She is alone on a Carolina beach, sweeping a stranded octopus into the sea.

Back in her office, she took the stacks of scientific reports and her notebooks and memories from the field and began to sketch a story, filling the spaces between paragraphs with her imagination.

“I really lived the things I wrote about,” she once told a friend.

These were the experiences that formed the basis for Carson’s first book, Under the Sea-Wind, published in 1941 and quickly submerged by news from a second World War. She kept working, supporting herself, her mother, and other members of her family.

In 1946, she saved money and her four weeks of annual vacation for a stay in Boothbay Harbor, Maine. She drove north from Maryland with her mother, Maria, and their two cats, and rented a cottage on the eastern shore of the Sheepscot River. It was a working vacation—reportedly Carson wanted to visit the federal lobster hatchery. But she had always wanted to go to Maine. She had written pamphlets about lobster, alewives, pollock, and cod. She must have heard about the tide pools that abounded on the rocky shores. Surely the fishermen and scientists and illustrators she worked with, who knew her enchantment with the sea, must have told her, “You have to go to Maine!”

So she went.

For four weeks she felt the wild, raw scrape of the sea against the granite coast. She learned to know by the gulls when a school of herring had entered the cove. In the fragrant, sun-warmed evergreen woods, she heard the song of a hermit thrush for the first time.

It was the beginning of the rest of her life.

Five years later, after her second book about the ocean, The Sea Around Us, became an immediate best seller (and stayed one for 86 weeks), Rachel Carson purchased land in Southport and built a summer cottage on a steep wooded hillside next to the Sheepscot. Below the mossy forest edge, ferns and purple asters grew in folds of quartzy rock that descended to a small triangle of beach surrounded by boulder and ledge.

She watched the falling tide pull the river from the weed-covered rocks, turning covelets into pools. She watched and listened as waves began to form and break over the outer ledges. Twice each day, the tide dragged away her stress about the present and her worry about the future, as spectacular secrets were laid bare at her feet.

There, at the salty edge of the Sheepscot, she found knowledge in the legions of barnacles, messages in the flashing lights of diatoms, meaning in the wisps of sea lace. “Contemplating the teeming life of the shore,” she would write in her third book about the ocean, Edge of the Sea, she had “an uneasy sense of the communication of some universal truth that lies just beyond our grasp.”

She wrote, “Like the sea itself, the shore fascinates us who return to it, the place of our dim ancestral beginnings. In the recurrent rhythms of tides and surf and in the varied life of the tide lines there is the obvious attraction of movement and change and beauty. There is also, I am convinced, a deeper fascination born of inner meaning and significance.”

In Maine, Rachel Carson could observe nature unimpeded, unguided, “her thoughts released to roam through the lonely spaces of the universe.” Nature offered intrigue, relief, consolation, restoration, hope. Carson needed these offerings because throughout her life, family, money, and her own poor health were always on her mind as she tried to advance in professions dominated by men. She reconciled her competing worlds by sharing her love of nature with family and friends. She advised others to do the same in an article in The Women’s Home Companion in 1956 titled “Help your child to wonder.”

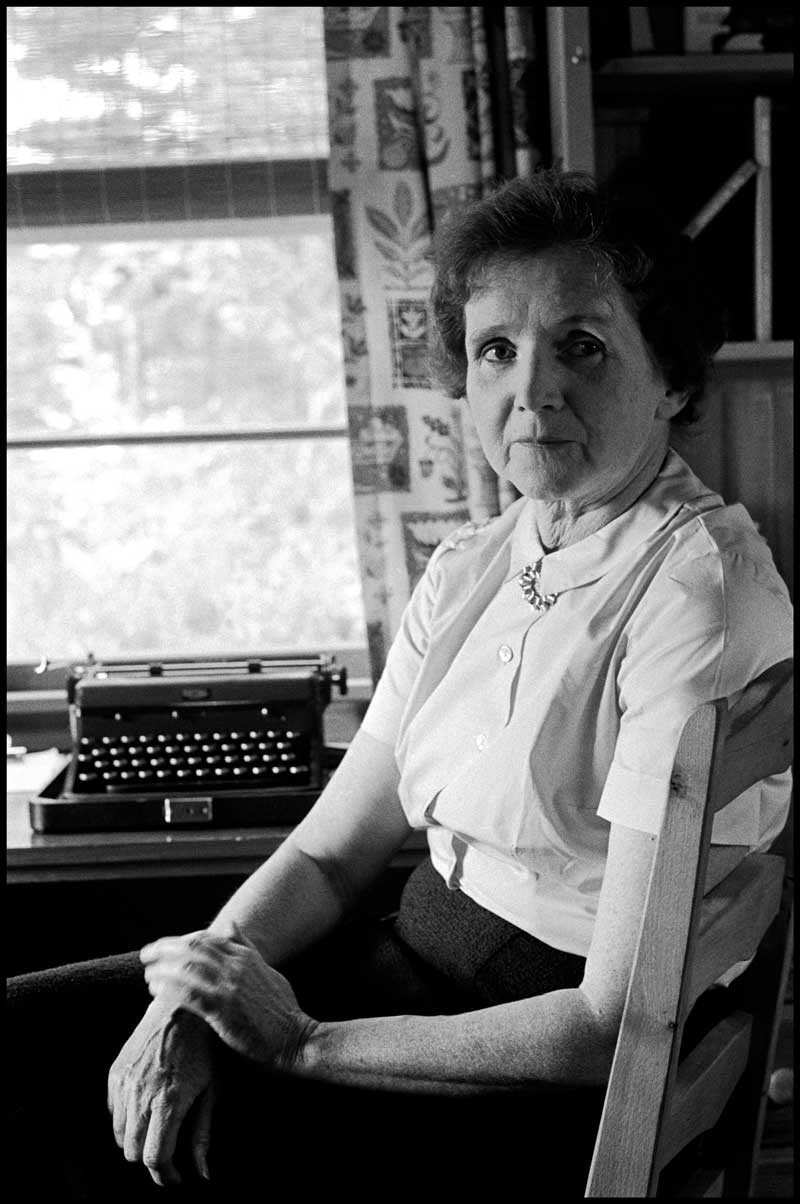

Rachel Carson at her typewriter, Southport 1961. Image courtesy Erich Hartmann / Magnum PhotosCarson believed, based on her own experience helping to care for her grand-nephew, that helping children to learn about nature could prevent them from being bored and disenchanted, preoccupied with artificial things, “alienated from the very essence of life.”

Rachel Carson at her typewriter, Southport 1961. Image courtesy Erich Hartmann / Magnum PhotosCarson believed, based on her own experience helping to care for her grand-nephew, that helping children to learn about nature could prevent them from being bored and disenchanted, preoccupied with artificial things, “alienated from the very essence of life.”

And by the 1950s, artificial things were starting to have an undeniable impact on the nature that Carson loved. Scientists had found disturbing effects of synthetic pesticides. Organic gardeners watched with dismay as airplanes sprayed DDT mixed with fuel oil across the landscape. Farmers found their cows’ milk contaminated. Suburban women watched in horror as songbirds died in their birdbaths. Carson took these facts from scattered newspapers, letters, government reports, and academic journals across the country, and connected them to each other, gradually building a damning case against the reckless use of chemicals.

A valiant defense of nature and future humanity, Silent Spring is evidence of how powerful a sense of wonder can be, giving rise to a compassionate love for others that can drive one to great ends. Rachel Carson knew what was at stake in a polluted society: the haunting song of the hermit thrush, the herring swimming between tide-swept ledges, the sanderlings running into the surf—the beauty, the vibrancy, the mystery of life on Earth.

As Jill Lepore wrote recently in the New Yorker, Carson couldn’t have written Silent Spring “if she hadn’t, for decades, scrambled down rocks, pulled up her pant legs, and waded into tide pools.”

In other writings and speeches, Carson was clear about this connection between examining and marveling at tide pools and a desire to protect nature, including people. She was one of the founding members of the Maine chapter of The Nature Conservancy, because she believed people needed sanctuaries, places they could go and walk and “get what they need…the peace and spiritual refreshment that our ‘civilization’ makes so difficult to achieve.”

“Help your child to wonder,” she wrote, because “the more clearly we can focus our attention on the wonders and realities of the universe about us the less taste we shall have for destruction.”

This is perhaps her most important message for this moment. In many ways, toxic pollution, including the heat-trapping carbon dioxide that has put the planet in an unprecedented and precarious state, has only worsened since Carson’s time. But lessons of climate change and microplastics will have no effect if young people have no direct experience with what they stand to lose. Rushing to teach the problem leaves no space, no time, for appreciation, curiosity, or wonder. And, as Carson demonstrated so vividly and lyrically, wonder is no inconsequential thing. Wonder leads to caring, to action. How will people learn to love nature and try to protect it if all they know is how it is in trouble, depleted, polluted, changing, and wrong?

Rachel Carson’s tiny triangle of tide-swept beach on the Sheepscot River as it looks today. Photo courtesy Catherine Schmitt

Rachel Carson’s tiny triangle of tide-swept beach on the Sheepscot River as it looks today. Photo courtesy Catherine Schmitt

“Help your child to wonder,” Carson advised, but she was writing about adults, too. She wanted everyone to know that “those who contemplate the beauty of the earth find reserves of strength that will endure as long as life lasts.”

As Carson defended her words against the well-funded attacks of the chemical industry representatives who tried to discredit Silent Spring and its author, she drew upon her own reserves of strength: memories of scientific excursions in the field, and the few precious summer days she could manage to spend in Maine each year.

The older she got, and the sicker she became with the cancer that had spread throughout her body, the more important it was to study periwinkles grazing the rocks, to search for the flash of iridescent blue from blades of Irish moss in a deep tide pool, to watch kingfishers work the shores. She found joy in the “throb of life” and healing in “the repeated refrains of nature.”

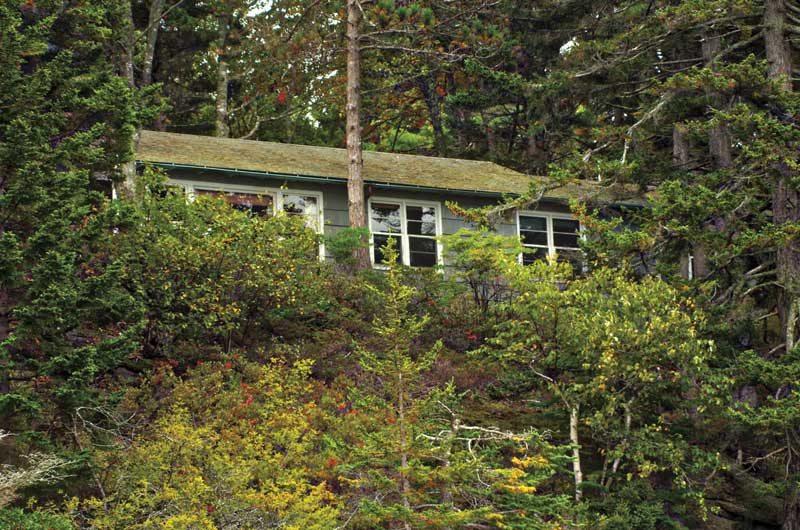

From the window at her desk, Carson could look into the forest or out to the shore. Photo courtesy Catherine Schmitt

From the window at her desk, Carson could look into the forest or out to the shore. Photo courtesy Catherine Schmitt

Rachel Carson’s cottage is still there on the Sheepscot River, much as it was, enjoyed by her family and guests. When the tide rises on the Sheepscot River, waves crest against the rockweed-coated shores, flooding the pools between ledges. New water flows over old, old rock and the shells on the beach roll over again and the sun sets, spectacular again, as the wind writes clouds across the sky. There, at the edge of the sea, a sense of wonder awaits.

Wonder can be found in every crack and crevice. Photo courtesy Catherine Schmitt

Wonder can be found in every crack and crevice. Photo courtesy Catherine Schmitt

While researching this article, Catherine Schmitt visited Carson’s cottage, with support from Maine Sea Grant, where she worked for 15 years writing about publicly-funded marine science. She is now a science communication specialist with Schoodic Institute at Acadia National Park.