Bigfoot, libidos, telephones?

There’s a museum for all that, and more, on Maine’s blue highways

PHOTOGRAPHS BY GREG ROSSEL

Years ago, the American road trip was about much more than getting from point A to point B in the most efficient way possible. In the pre-Interstate years, travel was a blue highway adventure, a way to discover the authentic nature of a region.

Back in the pre-Depression era, entrepreneurs and economic boosters of all stripes noted the potential of the motorcar to attract visitors and hence promoted a plethora of eclectic and eccentric landmarks, points of architectural and historical interest, and sometimes marvelous hucksterism. While many of these roadside wonders have disappeared in other parts of country, many still survive in the Pine Tree State—and some new ones have come along in recent years. Some are open all year long—others are open seasonally. Nearly all are worth a detour. Here is but a sampler.

Housed in a historic Kingfield schoolhouse, (just up the hill from the Ski Museum of Maine) is the Stanley Museum, which celebrates the inventive family best known for their steam-powered automobile. Most have heard of the twin Stanley brothers’ marvelous vehicles, which gave internal combustion and electric rivals a run for their money. In 1899 a Stanley Steamer conquered the summit of Mount Washington, and the canoe-shaped racer set the record at the time for the fastest mile in an automobile (127 mph) in 1906.

But the real Stanley family fortune came from lesser-known innovations such as the airbrush and their patented photographic dry plate manufacturing system—which by the turn of the 19th century was grossing them $1 million a year and was eventually sold to Eastman Kodak.

The museum’s collection covers all facets of Stanley family history and memorabilia—airbrush painting and photography, photographic dry plate technology, violins, and examples of Stanley steam cars from 1905, 1909, 1910, and 1916, including one probable rum runner.

This blue marlin caught by Ernest Hemingway in the 1930s off the Bahamas is one of the many intriguing items on display at the L.C. Bates Natural History Museum in Hinckley. Apparently Hemingway hired a Bangor taxidermist to mount the fish, but never got it back, and it ended up at the museum.

This blue marlin caught by Ernest Hemingway in the 1930s off the Bahamas is one of the many intriguing items on display at the L.C. Bates Natural History Museum in Hinckley. Apparently Hemingway hired a Bangor taxidermist to mount the fish, but never got it back, and it ended up at the museum.

Traveling U.S. 201 along the Kennebec River north from Waterville, one soon arrives at the campus of the former Good Will-Hinckley School and the remarkable L.C. Bates Natural History Museum. Here in a Romanesque revival building you can see such wonders as a giant clam, a marlin caught by Ernest Hemingway, a pair of tiny Chinese shoes that fit tiny bound feet, an amphora from the ruins of the palace of Nebuchadnezzar, an ancient cuneiform tablet, and an elegant stuffed double-wattled cassowary that formerly resided in New Guinea.

The story begins in 1889 when progressive preacher George W. Hinckley opened the Good Will farm school for underprivileged children. He also built a museum to house his collections from the natural world. Ever the promoter, he encouraged donations from a network of friends, luminaries, and even other museums.

Little has changed in the displays since the early 20th century—including the old school wood-and-glass cases, many containing lengthy handwritten descriptions of the artifacts. One can find ceramic pottery from Panama’s Chiriquí Indians and a pair of prodigious lobsters. Maine entomologist Emily “Mattie” Wadsworth’s collection of insects is here, as well as a couple of stuffed seals from a MacMillan polar expedition. There’s miniature circus memorabilia, a (stuffed) red-necked pademelon, an extinct passenger pigeon, bird nests from Burma, farm implements from the 1800s, and natural history dioramas created by American Impressionist painter Charles B. Hubbard.

The museum is also the home of the Maine state fossil, Pertica quadrifaria (a primitive plant that lived about 390 million years ago; the fossil was discovered in 1968 near Mt. Katahdin), and one of the last caribou killed in Maine.

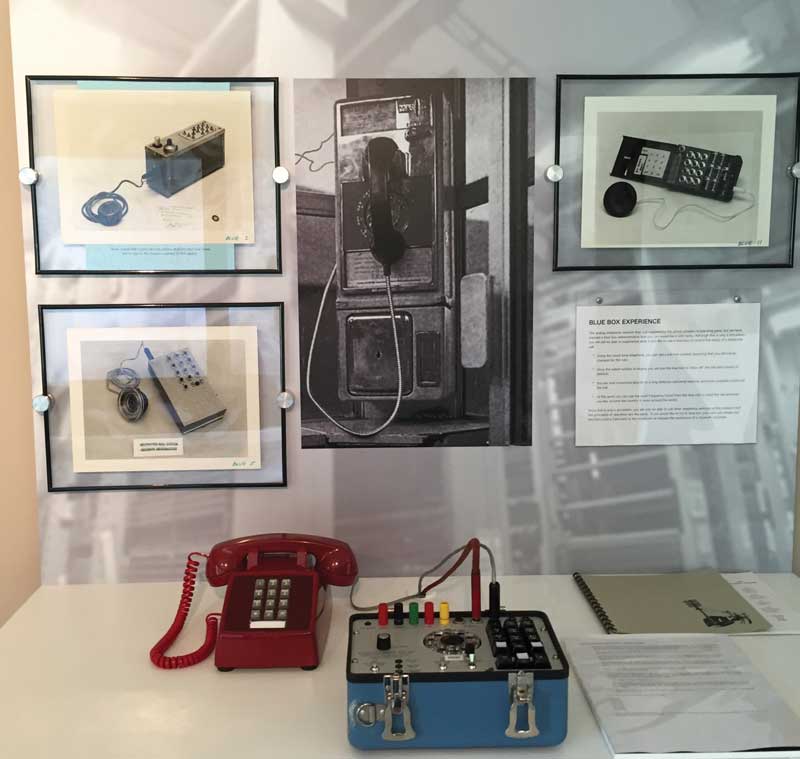

Displays at the Telephone Museum in Ellsworth trace the history of hard-wired communications.

Displays at the Telephone Museum in Ellsworth trace the history of hard-wired communications.

An entire generation today has never known anything but smartphones (or why you “dial” a number). But the real change agent of communication was the analog wired telephone which allowed (relatively) instantaneously, someone in Eastport, Maine, to visit with their neighbor down the road or chat with Cousin Chauncey in Chattanooga, Tennessee.

Just outside of Ellsworth, The Telephone Museum celebrates hard-wired communication, from 1876 with Alexander Graham Bell’s innovations, to 1986 and the breakup of Ma Bell.

This is technology the visitor can wrap their head around with hands-on interactive exhibits.

Visitors can make a call from a wall-mounted, hand-crank magneto phone to an operator at a wooden manual switchboard, and progress to the mechanical switching of the 1980s. You can even call Frenchboro Island (metaphorically) as the island’s central telephone office has been transplanted to a museum building. While there, find out how a Kansas City undertaker’s 1891 invention of automatic switching led to the dial telephone—the mainstay of telecommunications for more than 100 years.

This prodigious collection includes switches, switchboards, telephones, tools, schematics, photographs, and other items of telecommunications history.

Wilhelm Reich was a psychoanalyst who studied with Freud in the 1920s. After fleeing Germany in 1933, he began controversial experiments into the origins of life including the pursuit of “orgone” (what Freud tactfully described as libido). Reich claimed orgone was a human energy that affected the weather, gravity, and biological patterns and that could even cure cancer if properly harnessed. In the late 1940s he built a stone laboratory, an orgone energy observatory that he called “Orgonon,” overlooking Dodge Pond in Rangeley. This is now the Wilhelm Reich Museum. Reich’s novel theories won him few converts in the conventional medical and psychological fields. When he started selling his devices for medical relief, the feds stepped in, burned six tons of his publications, and sentenced him to two years in prison. He died of heart failure while incarcerated.

Visitors are introduced to Reich with a film, a tour, his inventions, and his art, library, and curious scientific apparatuses. There are orgone energy accumulators and measuring devices, “bion” experimental equipment, and cloud busters that Reich claimed could produce rain by manipulating the “orgone energy” present in the atmosphere. (A couple of blueberry farmers hired him in 1953; they apparently were satisfied enough to pay his fee.) While there, check out the 175 acres of self-guided nature trails for hiking or cross-country skiing.

This display at the Cryptozoology Museum includes models of a curious Orang Pendak (Indonesian for short person), a purported Civil War era Pterosaur aka Thunder Bird, and a Bigfoot head.

This display at the Cryptozoology Museum includes models of a curious Orang Pendak (Indonesian for short person), a purported Civil War era Pterosaur aka Thunder Bird, and a Bigfoot head.

Is he real or not? This 8' tall replica of the Crookston Bigfoot (from Crookston Minnesota, which is the Bigfoot capital of the world) stands guard at the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland.

Turn down the road to Portland’s rail and bus terminal, cross the tracks and head toward the water. There in a vintage brick building on Thomas Point Road you will find the International Cryptozoology Museum. The Oxford English Dictionary defines the noun cryptid as “an animal whose existence or survival to the present day is disputed or unsubstantiated.” Artifacts, models, and exhibits in this museum cover the Dover Demon, the Montauk Monster, the Jersey Devil, Thylacine (commonly known as the Tasmanian tiger), a 5½-foot-long Coelacanth model, fossils, hominids, skunk apes, and a colossal replica of an egg from the extinct Elephant Bird of Madagascar. A section covers the extinct Early-Middle Pleistocene Gigantopithecus blacki first discovered in the Far East in 1935. And no collection like this can be complete without the legend and mystery of Bigfoot, including footprint casts in cases, a full-size hirsute replica of the Crookston Bigfoot, and a purportedly authentic Yeti (Abominable Snowman) hair sample collected by Sir Edmund Hillary and Marlin Perkins during their 1960 World Book Expedition to the Himalaya. This is just a small part of over 10,000 items of interest gathered by museum founder and director Loren Coleman, who has been collecting for more than 40 years.

Is he real or not? This 8' tall replica of the Crookston Bigfoot (from Crookston Minnesota, which is the Bigfoot capital of the world) stands guard at the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland.

Turn down the road to Portland’s rail and bus terminal, cross the tracks and head toward the water. There in a vintage brick building on Thomas Point Road you will find the International Cryptozoology Museum. The Oxford English Dictionary defines the noun cryptid as “an animal whose existence or survival to the present day is disputed or unsubstantiated.” Artifacts, models, and exhibits in this museum cover the Dover Demon, the Montauk Monster, the Jersey Devil, Thylacine (commonly known as the Tasmanian tiger), a 5½-foot-long Coelacanth model, fossils, hominids, skunk apes, and a colossal replica of an egg from the extinct Elephant Bird of Madagascar. A section covers the extinct Early-Middle Pleistocene Gigantopithecus blacki first discovered in the Far East in 1935. And no collection like this can be complete without the legend and mystery of Bigfoot, including footprint casts in cases, a full-size hirsute replica of the Crookston Bigfoot, and a purportedly authentic Yeti (Abominable Snowman) hair sample collected by Sir Edmund Hillary and Marlin Perkins during their 1960 World Book Expedition to the Himalaya. This is just a small part of over 10,000 items of interest gathered by museum founder and director Loren Coleman, who has been collecting for more than 40 years.

“I began investigating local mysterious black panther sightings, apelike creatures, and giant snake reports from throughout the Midwest, while living in Decatur, Illinois,” he said. “I’ve traveled to 49 states doing field work. Every on-site investigation translated into a piece of physical evidence that I added to my collection.”

Some of the data may be fake, some may be the real deal. Some critters may just have yet to be identified or documented. Take the case of the coelacanth, a fish believed to be extinct since the end of the Cretaceous until a living specimen was discovered in 1938, or the “plausible” possible sightings of a Tasmanian tiger in northern Queensland, Australia, that have recently prompted scientists to undertake a search for the species, which was thought to have died out more than 80 years ago.

You never know unless you look.

Greg Rössel lives in Troy and is a boatbuilder, instructor at the WoodenBoat School, author, and host of “A World Of Music” on WERU fm.

For More Information

Stanley Museum, 40 School St., Kingfield.

207-265-2729; or www.stanleymuseum.org

L.C. Bates Museum, 14 Easler Road, Hinckley (just off Route 201). www.gwh.org

The Telephone Museum, 166 Winkumpaugh Rd., Ellsworth (one-half mile off Route 1A). 207-667-9491; www.thetelephonemuseum.org

Wilhelm Reich Museum, Dodge Pond Road, Rangeley. 207-864-3443;

www.wilhelmreichtrust.org

International Cryptozoology Museum, 4 Thompsons Point Road, Portland. www.cryptozoologymuseum.com

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.