Shipping News

From Maine to Iceland on a container ship

Photographs by Jonathan Laurence

Artists Anneli Skaar and Jonathan Laurence sailed in February 2016 on an Eimskip container ship, Selfoss, from Portland, Maine, to Reykjavik, Iceland, seeking both creative inspiration and a better understanding of the growing connection between Maine and Iceland. The Icelandic company Eimskip opened an office on the Portland, Maine, waterfront in 2013, and has shipped more and more goods to and from Maine, Iceland, and Europe ever since. The niche shipping line specializes in transporting products that need refrigeration. Products that come into this country include primarily frozen fish, bottled water, and cryolite—a mineral important in the production of aluminum.

Exports from Portland include consumer goods; foodstuffs, such as lobsters, blueberries, and potatoes; and building supplies from manufacturers throughout the United States.

The following are edited excerpts from Skaar’s daily journal. After leaving Portland during an evening snowstorm, Selfoss sailed up the coast to Argentia, Newfoundland, and then ended the trip in Reykjavik. The trip took nine days. —The Editors

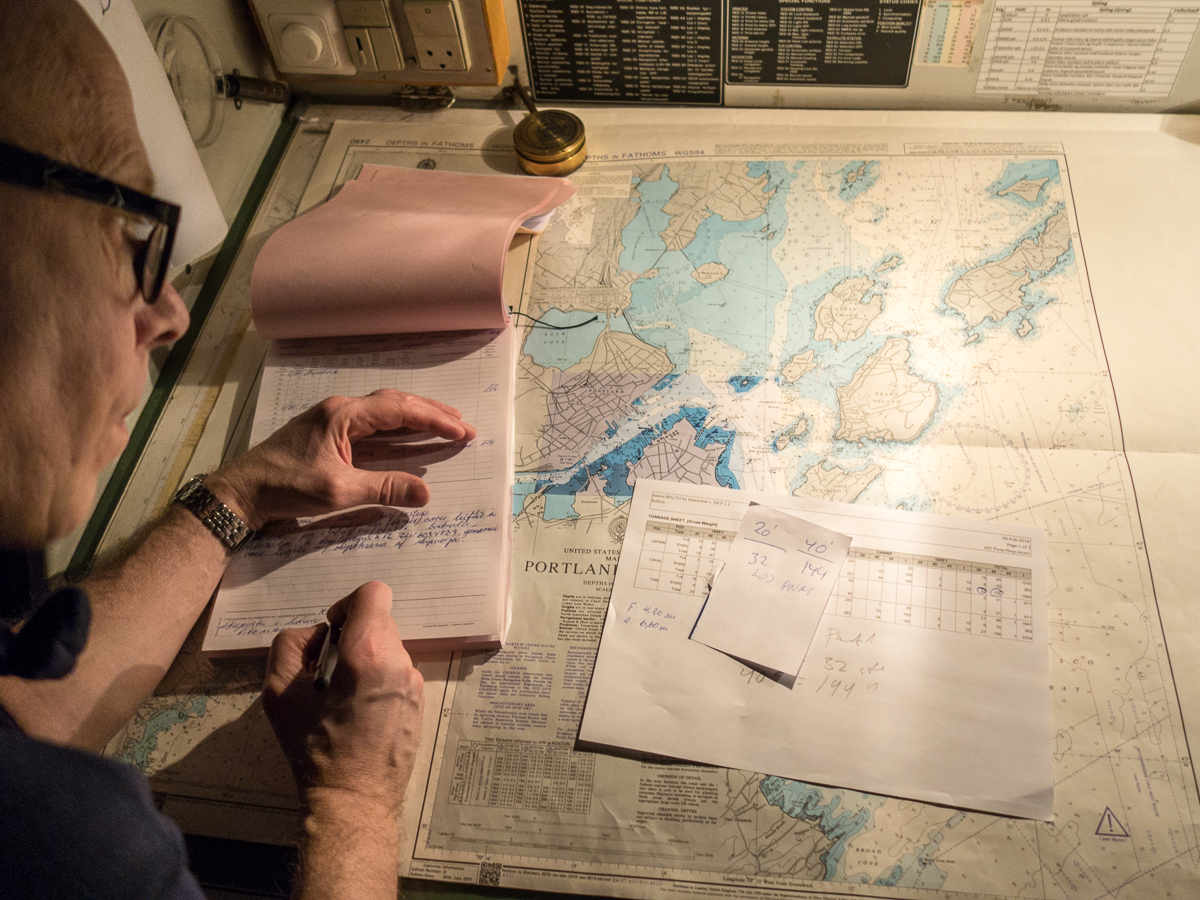

Chief Officer Einar Gudmundsson logs the departure of Selfoss from Portland Harbor. The crew uses electronic aids to navigations, but charts still play a role.

Chief Officer Einar Gudmundsson logs the departure of Selfoss from Portland Harbor. The crew uses electronic aids to navigations, but charts still play a role.

Typically Selfoss carries as many as 350 40-foot containers, many of them refrigerated.

Life on a ship in the open ocean is something special. After a few days at sea, we realize that very few things take you completely off the grid like this. Besides the brief access to the captain’s computer, we have no Wi-Fi, no cell service, no microphones on devices recording conversations, and no credit cards tracking our every move here in the North Atlantic. We have full days of uninterrupted time to focus on our work.

Typically Selfoss carries as many as 350 40-foot containers, many of them refrigerated.

Life on a ship in the open ocean is something special. After a few days at sea, we realize that very few things take you completely off the grid like this. Besides the brief access to the captain’s computer, we have no Wi-Fi, no cell service, no microphones on devices recording conversations, and no credit cards tracking our every move here in the North Atlantic. We have full days of uninterrupted time to focus on our work.

Freedom onboard, though, is not so much about a feeling of being relieved of obligations on land as much as it is a sense of being completely invisible. The view out my window right now is the bow of the ship in snow and sleet, a few hundred yards of waves beyond that, and then a wall of fog. Thousands of miles of nothing are beyond that. We exist as a blue shape on screen on a vessel tracker—in the words of Carl Sagan, a pale, blue dot.

I talked a bit about freedom with the ship’s captain, Karl “Kalli” Guðmundsson, over coffee in the smoking room— about the fact that both Jonathan and I feel as if huge weights have been lifted temporarily off our shoulders. Our minds are free to wander creatively, without constant interruptions and requests.

I also ask him if there are a lot of ships on this route, if we will see anyone else on our way east.

“No, we would be surprised to see anyone else out here,” he answers, “We’re alone.”

I let this sink in. It’s thrilling, but also a bit unnerving.

There’s a sense of calm in the air—the course is set for Iceland and there’s not much else to do but focus on work at hand and enjoy our forced rest until we reach Reykjavik.

We discuss the weather conditions for the next week, and the expression “gammel sjø”—old sea. It’s a type of ocean condition where the air is calm, but the ocean is rough with leftover waves from a past storm. The waves are not as harsh or as powerful as during the storm, the edge is off of them, but they are still there—still big and still rolling around the ocean like a memory.

Two cranes on board Selfoss load and unload containers, one at a time. It can take a whole day to load or unload the boat.

A friend of mine, Maria Randolph, lost her young niece Danielle in the El Faro sinking last fall. Danielle worked on board as crew. The loss of El Faro during a hurricane in the Caribbean was felt strongly in Maine as several of the souls onboard the ill-fated ship had Maine connections. Like gammel sjø, those storm waves are still there, months later, rolling along. Before leaving Portland I asked if I could bring something of Danielle’s with me on this trip. Maria graciously gave me a few things, including Danielle’s photo and some dried flowers from her memorial. The photo of Danielle, beautiful, bright-eyed, and smiling—with shipping containers behind her—has her own quote on it: “It’s always hard the first day back but nothing is as awesome as being on a ship…such freedom.”

Two cranes on board Selfoss load and unload containers, one at a time. It can take a whole day to load or unload the boat.

A friend of mine, Maria Randolph, lost her young niece Danielle in the El Faro sinking last fall. Danielle worked on board as crew. The loss of El Faro during a hurricane in the Caribbean was felt strongly in Maine as several of the souls onboard the ill-fated ship had Maine connections. Like gammel sjø, those storm waves are still there, months later, rolling along. Before leaving Portland I asked if I could bring something of Danielle’s with me on this trip. Maria graciously gave me a few things, including Danielle’s photo and some dried flowers from her memorial. The photo of Danielle, beautiful, bright-eyed, and smiling—with shipping containers behind her—has her own quote on it: “It’s always hard the first day back but nothing is as awesome as being on a ship…such freedom.”

I pinned the photo onto the bulletin board in our cabin when we came aboard in Portland. But it’s really not until the last day or two, out in the empty regions of the ocean, that I really understand the quote. The captain, on one of his visits in the past week, saw the image of Danielle and I explained the story behind it. He was silent for a moment and then he put it more eloquently than I ever could: “She is sailing the eighth sea now.”

Captain Karl “Kalli” Guðmundsson maneuvers Selfoss out of Portland at night. The route of the 415-foot ship takes it between Portland, Maine; Argentia, Newfoundland; Reykjavik and two more ports in Iceland; then England, and Rotterdam and back again. The whole route takes about five weeks.

I will leave the photo on this ship, tucked away somewhere safe. I like to think that Danielle will keep on sailing for a good while longer, perhaps for many, many years. When it’s not so rough out and I can go on deck safely, I’ll toss the dried flowers into the North Atlantic. I will be sure to do it discreetly.

Captain Karl “Kalli” Guðmundsson maneuvers Selfoss out of Portland at night. The route of the 415-foot ship takes it between Portland, Maine; Argentia, Newfoundland; Reykjavik and two more ports in Iceland; then England, and Rotterdam and back again. The whole route takes about five weeks.

I will leave the photo on this ship, tucked away somewhere safe. I like to think that Danielle will keep on sailing for a good while longer, perhaps for many, many years. When it’s not so rough out and I can go on deck safely, I’ll toss the dried flowers into the North Atlantic. I will be sure to do it discreetly.

No photos will be taken, no video. Invisible. Such freedom.

Thanks to GPS, satellites, radars, and weather reports, the crew can predict when we will get to Iceland, almost within the hour. Back when Vikings crossed the ocean hundreds of years ago, they would have a raven on board. Scouting ahead into the fog, this raven might bring back a piece of vegetation—a stick, a leaf, or something green from the mainland—to confirm that the ship was close to land. It would be a small thing that would make proximity of solid ground very real. Aboard Selfoss, this green signal is Astroturf.

For a good week the television in the tiny smoking room has shown the Danish words “Intet Signal”—no signal—on the screen. As we get closer to shore, a soccer game begins showing up sporadically, pixelated, and flickering in and out. The grass green of the turf looks juicy and rich in the small beige and blue cabin. It’s a sign we are closer to civilization.

The deck of the tanker at sea can be treacherous. Pumps located at foot level periodically flood the decks with seawater in order to keep ice buildup to a minimum.

“That’s my team, Barcelona,” nods Captain Kalli, as somebody on the team kicks the ball and the signal once again disappears and image collapses into a flurry of green pixels.

The deck of the tanker at sea can be treacherous. Pumps located at foot level periodically flood the decks with seawater in order to keep ice buildup to a minimum.

“That’s my team, Barcelona,” nods Captain Kalli, as somebody on the team kicks the ball and the signal once again disappears and image collapses into a flurry of green pixels.

The window in the smoking room shows the massive waves and the dense fog surrounding the ship. Selfoss is rolling heavily and she sounds like she is snoring—each roll is the sound and speed of a deep inhale and exhale. I believe your breathing slows down to follow the ship’s breath when you are on board.

Grass green isn’t part of the palette here at all. Life on the ship is mostly beige, blue, orange, yellow, and red. Any bright green found on this ship is on the numerous warning signs that function like cryptic menus informing us of all the varieties of ways we can slide into the ocean, lose digits, and puncture eyeballs by accident.

The captain tells me that most of the crew will spend a lot of time outdoors in nature once off the ship, soaking up some green as it were. Delicious, grassy, leafy green. The story goes that Greenland was so named although it was all ice and icebergs, and Iceland named Iceland despite its verdant nature. Basically an elaborate ruse to mess with unwanted visitors.

“The last captain died in bed,” Captain Kalli says, and points to his bedroom. Jonathan and I have heard some talk about a ghost on board who likes to stay on the bridge. Kalli tells us that he has not seen it, but that a few others claim they have. They think maybe it’s the dead captain.

The bridge on the container ship Selfoss is seven stories up. The living spaces for the crew are housed in the tower below the bridge.

It seems strangely fitting that a spirit would be traveling with us. The powerful thing about an ocean voyage is not so much the day-to-day workings of the ship, but the fact that you are not within reach of anyone. You are truly alone and ghostlike on the ocean. We can paint, write, photograph, or watch silly movies in the day room all we like, but if something happens, this is really it—this group of people, and this equipment. You can reach out to the whole world online, but you might as well be on the moon if there’s an emergency. Sure, there are lots of opportunities to feel this way on land as well, but there is something about being on a pitch-black ocean with thousands of feet of empty space below that is quite mind boggling if you let your thoughts go there.

The bridge on the container ship Selfoss is seven stories up. The living spaces for the crew are housed in the tower below the bridge.

It seems strangely fitting that a spirit would be traveling with us. The powerful thing about an ocean voyage is not so much the day-to-day workings of the ship, but the fact that you are not within reach of anyone. You are truly alone and ghostlike on the ocean. We can paint, write, photograph, or watch silly movies in the day room all we like, but if something happens, this is really it—this group of people, and this equipment. You can reach out to the whole world online, but you might as well be on the moon if there’s an emergency. Sure, there are lots of opportunities to feel this way on land as well, but there is something about being on a pitch-black ocean with thousands of feet of empty space below that is quite mind boggling if you let your thoughts go there.

And if we’re really honest with ourselves, isn’t this voyage just a great, scenic allegory for life in general? For the faint of heart, this thought is quickly quelled by a warm waffle with jam in the mess room.

Every six hours a crew member checks each refrigerated container and the ties holding them down. The containers are tracked using a digital recorder, which logs temperature and other data.

Atli works as crew, squeezing in between massive stacks of steel containers on deck, checking numbers, tightening bolts, and generally operating in extremely dicey conditions as his workplace rolls like a roller coaster around him. Jonathan has been mercilessly shadowing him and others with equally crazy jobs with his camera, getting into every tiny corner of the ship, from inside the cranes 80 feet above the roiling ocean to the rusty bowels of the hull. All accompanied by nothing but ocean in every direction.

Every six hours a crew member checks each refrigerated container and the ties holding them down. The containers are tracked using a digital recorder, which logs temperature and other data.

Atli works as crew, squeezing in between massive stacks of steel containers on deck, checking numbers, tightening bolts, and generally operating in extremely dicey conditions as his workplace rolls like a roller coaster around him. Jonathan has been mercilessly shadowing him and others with equally crazy jobs with his camera, getting into every tiny corner of the ship, from inside the cranes 80 feet above the roiling ocean to the rusty bowels of the hull. All accompanied by nothing but ocean in every direction.

“Life is just sacrifice, isn’t it,” Atli says. I’ve caught up with him on a break, and he has a cup of coffee in front of him and some tobacco tucked into his upper lip. His family, including two young children, lives in Norway, and he has a horse farm in Iceland. He has 19 horses; it’s his family’s hobby. “I can work long shifts here, and because it pays better than most jobs, I can have the horse farm as well. I spend the summer there.”

We couldn’t possibly have more different jobs he and I, but we discuss the similarities of working at sea and of single parenthood—having time off and time on to focus on what’s important in life. How the sacrifice of time to work hard also allows you the life you want when you have time off. Atli’s only regret is that his daughter takes so long to recognize him between his five-week stints at sea. I tell him how my son is off with his dad for three months and how I worry that our connection will be lost. We are both experiencing periods of being absent from our own lives—somehow living half a life, in order to be more present in the half that matters.

“We are speaking the same language,” he says solemnly before finishing his coffee and heading back into the depths of the ship. I go back to my room to paint.

Hannes Guðlaugsson, the cook aboard Selfoss, is perhaps the most important person of an 11-person crew. Food of some sort is served about every three hours. Laurence and Skaar gave the food rave reviews.

Hannes Guðlaugsson, the cook aboard Selfoss, is perhaps the most important person of an 11-person crew. Food of some sort is served about every three hours. Laurence and Skaar gave the food rave reviews.

Late that evening when the ship is asleep, Jonathan and I go to the bridge. The night watch is on duty up there, along with a few others, their faces glowing from the light of the instruments. Maybe the dead captain is here, too, watching from the shadows in the back of the dark room. B.B. King plays loudly on the stereo, and through the 360-degree views the moon is shining on the black, deadly ocean. Ahead of us is the dark outline of the containers stacked on the deck.

Beyond that, a bright and ghostly green ribbon of northern lights leads the way to the coastal lights of Reykjavik.

Anneli Skaar is a painter and graphic designer whose current work explores the meeting and impact between society and the Arctic landscape. Jonathan Laurence, creative director at the Center for Maine Contemporary Art, is a multimedia designer, consultant, and educator who has worked internationally with companies, organizations, and individuals.

Anneli Skaar Slide Show

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.