Hooking Better Lives

Rug-making helped fishermen’s wives find their inner creativity

The Roaring Twenties were a time of prosperity for many; women had just received the right to vote, and the Jazz Age was in full swing. There was little jazz in downeast Maine, though, particularly for fishermen and their families. For them, making ends meet was hard, even in the best of times. Seeking to increase family incomes by putting fishermen’s wives to work, the Maine Sea Coast Mission began a hooked rug program in the 1920s.

A gathering of the South Gouldsboro rug-making circle, circa 1927. Historic images courtesy Maine Sea Coast Mission (3). Rug photos by Judith Burger-Gossart (2)

A gathering of the South Gouldsboro rug-making circle, circa 1927. Historic images courtesy Maine Sea Coast Mission (3). Rug photos by Judith Burger-Gossart (2)

The program was the inspiration of Alice Moore Peasley. Born in Rockland, Maine, in 1880 into a family of modest means, she went on to become a teacher, a minister, a nurse, and a notary public. Peasley joined the Bar Harbor-based Mission in 1917 as an assistant missionary. She taught school on various islands, conducted church services, and provided help for families with their everyday problems and needs. The seeds of the hooked rug program were planted and began to flower in 1923 when she was stationed in South Gouldsboro. As a child Peasley had helped her grandmother make hooked rugs, but otherwise had no formal training in rug hooking. She described herself as, “simply a New England woman who loved hooked rugs.”

In the isolated village of South Gouldsboro, people had courage and were willing to work, according to Peasley’s notes in the Sea Coast Mission’s archives. Imagination and playfulness seemed in short supply, however. Thinking rug hooking might be a good outlet, she taught the women in the community how to make rugs, which the Mission sold, putting much needed money into the women’s hands.

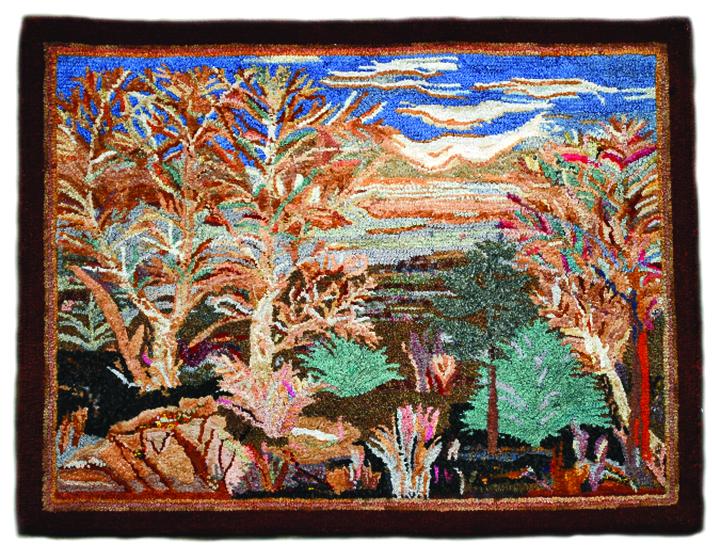

Forest Scene, one of 150+ rugs made by Mary Ann Bunker of South Gouldsboro.

Peasley was aware of the Grenfell Mission in Newfoundland and Labrador, which also had a hooked rug program for fishermen’s wives and by the 1920s was selling rugs around New England, and even in Bar Harbor to summer residents. She complained about the “rugs from Canada” muscling in on her territory, as the Canadian women produced and sold rugs for much less than the Sea Coast Mission did. The Newfoundland and Labrador women earned approximately $3.50 per mat, while the Maine Sea Coast Mission women received $15 to 20 for a rug: stiff competition indeed.

Forest Scene, one of 150+ rugs made by Mary Ann Bunker of South Gouldsboro.

Peasley was aware of the Grenfell Mission in Newfoundland and Labrador, which also had a hooked rug program for fishermen’s wives and by the 1920s was selling rugs around New England, and even in Bar Harbor to summer residents. She complained about the “rugs from Canada” muscling in on her territory, as the Canadian women produced and sold rugs for much less than the Sea Coast Mission did. The Newfoundland and Labrador women earned approximately $3.50 per mat, while the Maine Sea Coast Mission women received $15 to 20 for a rug: stiff competition indeed.

By the end of the first year, when it was apparent that Peasley’s program in South Gouldsboro was a success, other women along the coast asked to be included, and began making more hooked rugs for the Mission to sell. Peasley’s notes include a roll call for Maine’s island communities, among them: Frenchboro, Matinicus, Muscongus, Islesford, McKinley, Loudville, Little Deer Isle, Southwest Harbor, and Two Bush Island. According to her records, there were no more than 30 women hooking rugs at any one time. I estimate that approximately 650 rugs were made between 1923 and 1938, when orders for rugs dried up and the program ended. I have been able to identify 25 existing Mission rugs and many photographs of Mission rugs.

While some have a white label with red lettering reading “Maine Sea Coast Mission Rug,” many known Mission rugs carry no label. Another identifying feature of these rugs is the shearing technique—the surface loops were cut with scissors to a lower level freeing the material to expand and soften. As a result most Mission rugs have a soft plush surface.

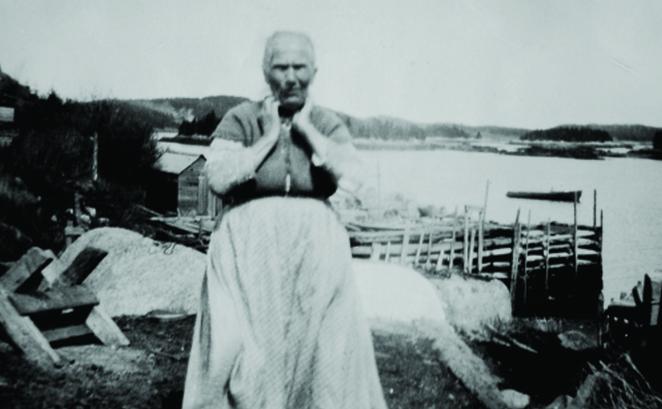

Alice Moore Peasley and the Rev. Bousfield aboard Sunbeam II.

In the first year or two, it appears that Peasley designed many of the rug patterns. She encouraged the women to use her designs, but they were allowed to choose their own colors and could alter the design if they wished. Over several years, her philosophy evolved to emphasize creativity. She encouraged the women to see the beauty around them and then translate that into a hooked rug.

Alice Moore Peasley and the Rev. Bousfield aboard Sunbeam II.

In the first year or two, it appears that Peasley designed many of the rug patterns. She encouraged the women to use her designs, but they were allowed to choose their own colors and could alter the design if they wished. Over several years, her philosophy evolved to emphasize creativity. She encouraged the women to see the beauty around them and then translate that into a hooked rug.

She wrote, “The output from this department will always be small, because of the nature of the work. Quantity has never been an end. Each rug receives the care needed to make it an individual and precious thing.” Peasley strove for individual expression and playfulness, elements that were scarce in the women’s challenging lives.

As a result, there is no one “look” to a Maine Sea Coast Mission rug; rather, there are the “looks” of the individual artists such as Mary Ann Bunker, Henriette Ames, Sadie Lunt, and the many unknown women who made rugs depicting primitive animals, houses, and seascapes. The rugs made by these fishermen’s wives tell us volumes about their lives, their dreams, and their desires.

Many of the primitive house design rugs have homes with huge windows and doors, not the typical fisherman’s home. It seems the women were yearning for light to stream through large windows, when in reality their homes had rather small windows to keep in the precious heat from the wood stoves. Domestic and wild animals are also featured in many of the designs. These animals are charming and endearingly portrayed. Human relationships in isolated communities can be tense and difficult at times, clearly animals were seen as friendly, engaging, and nonthreatening.

Mary Ann Bunker, who lived her life in South Gouldsboro, exemplifies the artistic transformation that took place as the women developed skills. Bunker began by making lovely but conventional pansy rugs. Within two years she moved to making tapestry rugs: her version of scenes from nature. They are painterly, nuanced, and some are much like an impressionist painting.

Sadie Lunt on Frenchboro had lived a hard life and endured many personal losses, but was a talented and imaginative rug hooker.

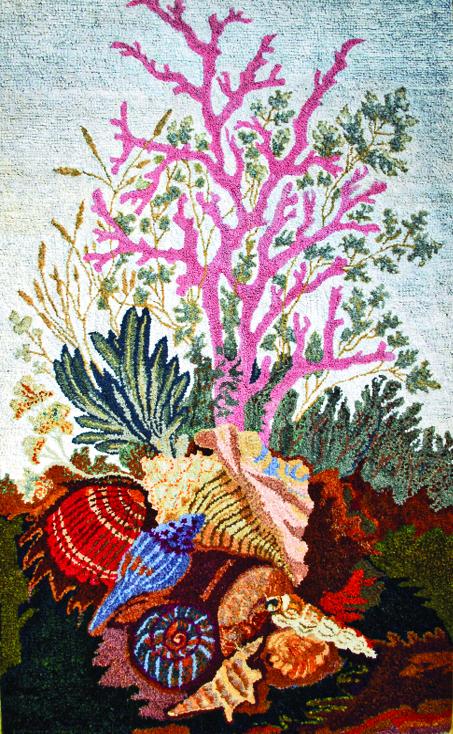

Sadie Lunt, poor and isolated on the remote island of Frenchboro, had lost two of her three children. Despite her hardscrabble life, she possessed a hidden reserve that Peasley tapped. Lunt produced a remarkable hooked rug depicting tropical shells—perhaps she was dreaming of the tropics during a cold Maine winter.

Sadie Lunt on Frenchboro had lived a hard life and endured many personal losses, but was a talented and imaginative rug hooker.

Sadie Lunt, poor and isolated on the remote island of Frenchboro, had lost two of her three children. Despite her hardscrabble life, she possessed a hidden reserve that Peasley tapped. Lunt produced a remarkable hooked rug depicting tropical shells—perhaps she was dreaming of the tropics during a cold Maine winter.

Henriette Ames from Matinicus made rugs depicting Sunbeam and the Julia Fairbanks demonstrating the importance of the island’s connection to the outside world. The Sunbeam was the outreach boat for the Mission and the Julia Fairbanks was a passenger and freight boat that plied the waters between Rockland and Matinicus in the late 1800s, during Ames’ youth. She also hooked several images of her home on Matinicus; these rugs radiate the domestic tranquility that she so admired.

From her Maine island home, Sadie Lunt captured the vivid tropical corals and shells of a very different environment in Still Life, Tropical Marine.

Peasley’s ability to interact with these women nurtured creativity in unlikely places. “I never thought I would live to see the day when I could do something that somebody else would really want and value,” one participant said. Peasley suggested to this rug-maker that she reproduce her own backyard, instead of using an unvarying green backdrop.

From her Maine island home, Sadie Lunt captured the vivid tropical corals and shells of a very different environment in Still Life, Tropical Marine.

Peasley’s ability to interact with these women nurtured creativity in unlikely places. “I never thought I would live to see the day when I could do something that somebody else would really want and value,” one participant said. Peasley suggested to this rug-maker that she reproduce her own backyard, instead of using an unvarying green backdrop.

“There’s a deep shadow under the pine tree and the path from your door is really a soft greenish tan,” she told the woman. “She looked in silence for a long time,” recalled Peasley, “and then said, ‘Well, I reckon this is the first time I ever saw my own backyard. A body can’t hook what she doesn’t see.’”

Peasley, who sought to empower the women of coastal Maine, would be both surprised and pleased to know that the rugs she inspired are still treasured and valued today, perhaps more than ever before.

Judith Burger-Gossart is a historian and an antique dealer who lives in Salsbury Cove, Maine. She has curated hooked rug exhibits and catalogs, designs and makes her own rugs, and is the author of a new book about the early years of the Maine Sea Coast Mission rug-hooking project.

This article was adapted by the author from Sadie’s Winter Dream: Fishermen’s Wives & Maine Sea Coast Mission Hooked Rugs, 1923-1938, by Judith Burger-Gossart (Maine Authors Publishing, 2015, 121 pages paperback). The book is available via maineauthorspublishing.com.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.