Small Adventures: Damariscotta Lake

Big on Nature

Bordered by Newcastle, Jefferson, and Nobleboro, Damariscotta Lake is Lincoln County’s largest body of fresh water. Yet before exploring with friends in their 22-foot Grady White, I’d never grasped the full extent of its impressive 4,300-acre, 14-mile-long expanse. We spent the day skimming across 100-foot-deep Great Bay, puttering through the lake’s narrow waist, prowling its two lower legs in search of resident eagles, and stopping in a cul-de-sac to picnic and swim.

Daytrippers like us are welcome on this lake. Paddlers can put in at numerous spots, including the beach at Damariscotta Lake State Park in Jefferson. For trailered boats, there’s a state ramp on Route 213, also in Jefferson, and a smaller ramp on Vannah Road in Nobleboro. There are no facilities, however, so be sure you have sufficient gas. If you’re after the lake’s largemouth and smallmouth bass, landlocked salmon, and trout, bring a freshwater fishing license.

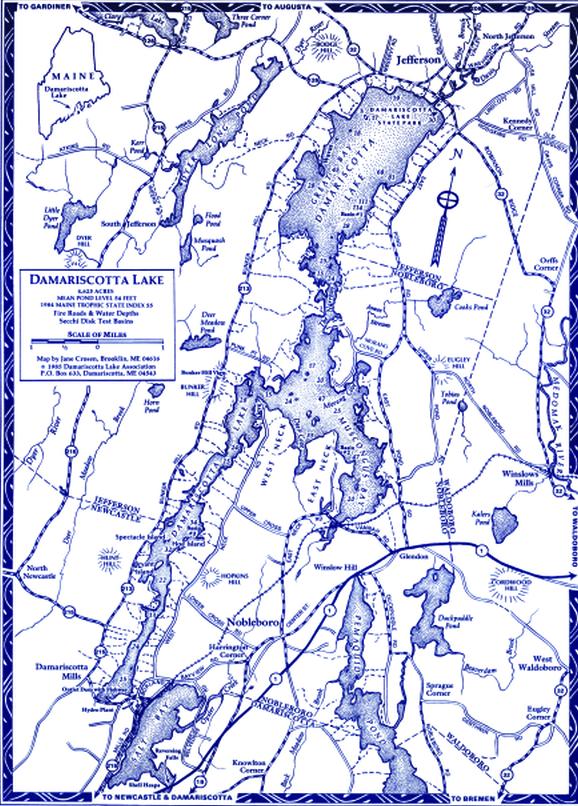

Consult a chart, too, advised Bobby Whear, owner with his wife of the Millpond Inn at the lake’s southwestern tip. “I’ve been boating here for 30 years,” he told me, “and I’m still finding rocks.”  Damariscotta Lake has many rocks, so if you go be sure to get a map. Copies of this chart are available from the Damariscotta Lake Watershed Association, P.O. Box 3, Jefferson, ME 04348.

Damariscotta Lake has many rocks, so if you go be sure to get a map. Copies of this chart are available from the Damariscotta Lake Watershed Association, P.O. Box 3, Jefferson, ME 04348.

Charts can be purchased at the Damariscotta Lake Watershed Association office, on the shore in Jefferson. Committed to a healthy lake, the DLWA is working to eradicate two small patches of invasive hydrilla. Its volunteers are also planting a buffer of vegetation along the shoreline where cleared land has allowed an increased flow of phosphorus-laden rainwater into the lake. Phosphorus encourages algae bloom, which robs the water of oxygen.

While invasive milfoil is a concern on many Maine lakes, there is none here. Lake stewards want to keep it that way; so on weekends volunteers check boats being launched both for the required lake protection sticker and to make sure boats are vegetation free.

Stewards of the lake also include Camp Kieve for boys and its sister camp, Wavus. Perched on opposite shores, they welcome thousands of youngsters every summer. In winter, Kieve-Wavus Education partners with Maine schools, reaching students throughout the state.

Another group caring for the lake is the cadre of volunteers who have spent the past eight years restoring an 1807 fish ladder in Damariscotta Mills, a picturesque village in Newcastle. Built to allow alewives (a species of herring) to bypass a dam as they travel into the lake to spawn, the ladder was crumbling by the late 1990s. The number of fish had dropped so dramatically, traditional harvesting of a portion of them was suspended.

“Fish were getting caught in gaps and dying,” said Deb Wilson, chairman of the restoration project. “Something had to be done.”

Thanks to untold hours of work and $1 million in donations, the ladder is again part of Maine’s most productive alewife fishery. The fish count topped one million last year, and lobstermen are once more lining up to purchase their quota of alewives, prized as bait.

At an annual Fish Ladder Festival on Memorial Day Weekend, visitors can watch the fish swim and leap up through water cascading down the 42-foot-tall stretch of rock pools and weirs. There’s live music, plus lots of food. For adventurous eaters, there are smoked alewives from the Mulligan sisters’ old-fashioned smokehouse across the road. (I have tried them; once was enough.)

Back in 1948, naturalist Henry Beston, who lived nearby with his wife, poet Elizabeth Coatsworth, wrote about the alewife run in his book, Northern Farm. Reflecting on the importance of the lake’s natural cycles, he warned against putting ourselves “outside of nature, of which we are inescapably a part.”

Damariscotta Lake plays peekaboo with the roads that trace its meandering edge. The spectacular exception is the panorama visible from atop Bunker Hill, on Route 213 in Jefferson. Whenever I find myself here, I can’t resist pulling over to absorb the beauty. As I do, I am grateful the lake’s current caretakers, like Beston, believe we are inescapably a part of nature.

Mimi Bigelow Steadman lives on the Damariscotta River in Edgecomb.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.