A moose was among the many wonderful sights encountered during a recent canoe trip on the Allagash Wilderness Waterway. Photo by Andrew Veilleux

A moose was among the many wonderful sights encountered during a recent canoe trip on the Allagash Wilderness Waterway. Photo by Andrew Veilleux

Considered one of Maine’s natural treasures, the Allagash Wilderness Waterway flows north some 92 miles and features a string of singular lakes along the way. One of the guide-and-map brochures produced by the Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation, and Forestry cautions that the “Allagash Wilderness Waterway is not the place for an inexperienced person to learn canoeing or canoe camping alone.” Lucky for me I had the best paddling companions.

The trip began with a call from Ron Beard, host of WERU’s “Talk of the Towns,” adjunct faculty member at College of the Atlantic, Jesup Library board chair, professional consensus builder, aficionado of all things Scottish—and a canoeist. He asked if I’d like to join his band of canoeing brothers for a week on the Allagash in mid-June. Yes, please, said I.

Mid-river meeting: getting the news of the day from Allagash River Ranger Trevor O’Leary. Photo by Ron Beard

Mid-river meeting: getting the news of the day from Allagash River Ranger Trevor O’Leary. Photo by Ron Beard

Next, I met with Ted Koffman, a friend from my College of the Atlantic days, former legislator from Bar Harbor and former director of Maine Audubon. He would be the sternman, leading me through rapids and around boulders. He would tell me to push or pull, sometimes with urgency.

At an outside table at Choco Latte in Bar Harbor, Koffman reviewed a list of items necessary for the trip. The things I would need included the obvious—bug dope, tent, toothbrush—and the less apparent: dry pants, wool hat (in summer?), and “libation of choice.”

In addition to Koffman and Beard, the crew included Tom Crikelair, an engineer and transit planner, and father and son Greg and Andrew Veilleux, the former, co-owner of the home furnishings shop Windowpanes in Bar Harbor, the latter, a loan officer at Camden National Bank. All five of them knew the Allagash like the backs of their hands, which made me a very fortunate first-timer.

To prepare for the fly-fishing part of the excursion, I turned to my next-door neighbor in Somesville, John Sargeant Pepper, a registered Maine Guide and owner of Acadia Fly Fishing. He brought over a rod and guided me in a casting session on the lawn. Later we spent a couple of hours practicing on Seal Cove Pond. My confidence level rose even as I knew I’d be in the company of seasoned fly fishermen.

The day before we left, we met at Hannaford in Bar Harbor, where Beard gave out food-gathering assignments. Back at Crikelair’s house on the Crooked Road, we sorted and packed, using coolers and wangans, wooden boxes with handles for storing food. Early the next morning we loaded up a truck, tethered the canoes to the roof, and headed north and west, about a six-hour drive if you count a bathroom break in Medway and breakfast in Patten.

We put in at Churchill Dam, the canoes loaded to the gunwales, and spent that night and the next day at Scofield Point, the first in a series of perfectly situated campsites. My fellow travelers knew the best spots on the waterway.

I took along a pocket diary my son gave me years ago and made several entries over the six days. Our first night I noted that a game warden came by to check on us. He mentioned how much he loved being on Churchill Lake compared to Sebago—fewer people, more nature. He immediately became a model for what Paul Doiron’s famous fictional game warden Mike Bowditch might look like.

Full canoes await at the Grey Brook campsite. Photo by Carl Little

Full canoes await at the Grey Brook campsite. Photo by Carl Little

Monday morning, we returned to Churchill Dam, unpacked, and sent supplies ahead in preparation to take Chase Rapids in empty canoes (don’t want to tip over with cargo aboard). Koffman suggested I kneel at the bow—the best position to take on the thrashing waters and perhaps, I thought afterward, to pray. Aside from catching a standing wave in the face, the transit went smoothly as we slalomed down the river. This was my first rodeo.

There was more excitement ahead. As we approached our second campsite, Grey Brook on Long Lake, the heavens looked shaky. Koffman and I had lagged a bit behind; when he saw a downpour in our immediate future, he called out, “Push!” We paddled like crazy the remaining stretch, landed, unpacked, set up tents, and settled just as the rain came down. And I mean came down: the drops beat the surface of the lake.

The next day we made it to Round Pond, perhaps the most picturesque of our stops. Veilleux père and fils, who had joined us at Chase Rapids, invited me to join them for a paddle at dusk. As we turned into an opening in the greenery, Andrew whispered, “Moose.” The creature stood in the water not 20 yards away and as we approached in silent mode it turned, caught sight of us, and clambered onto the bank and into the underbrush.

Another high point of the trip was meeting up with Allagash ranger Trevor O’Leary one morning as we headed for Cunliffe Depot, our last stop before taking out at Michaud Farm. Broadside to O’Leary’s canoe we floated down the middle of the river, catching up on some Maine news and asking about his renowned moose-calling skills.

As a guest paddler, as it were, on this expedition I wanted to contribute something beyond a container of my wife’s supreme homemade chili (with cashews to add). I put together a small sheaf of poems, a couple for each night, that would relate (or not) to our river-borne circumstances. I read Elizabeth Bishop’s “The Fish” and “The Moose,” a poem by each of Maine’s six poet laureates, several story poems by William Carpenter, a couple by Nikki Giovanni, “My Heart’s in the Highlands” by Robert Burns in honor of Beard, and a few of my own. They were, I’m pleased to report, well received.

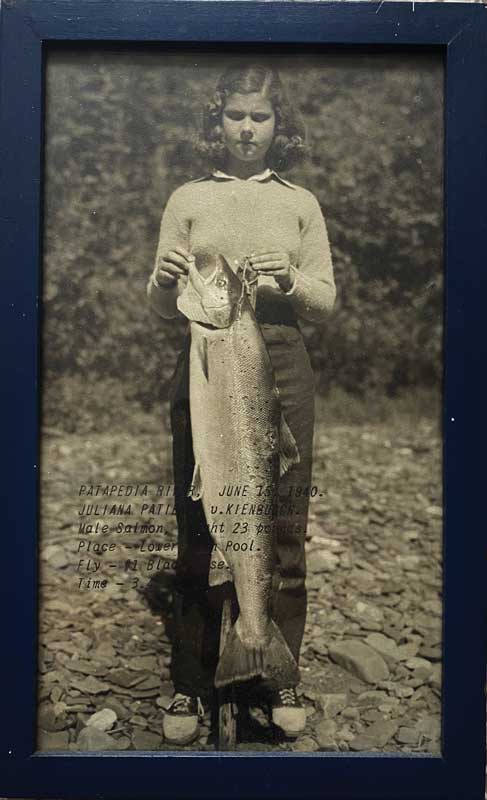

The author’s 14-year-old mother, Juliana Patience von Kienbusch, holds the 23-pound salmon she caught on the Patapedia River on June 15, 1940. Photo courtesy the authorThe trip represented something of a nod to personal history. My grandfather, Carl Otto von Kienbusch, from whom I got part of my name, was a flyfishing devotee. Each summer he would lease a section of the Patapedia River in Quebec, take the train from Penn Station north, and set up camp in a houseboat. Looking at photos of my teenage mother holding a salmon almost as long as she was tall my admiration grew for her piscatorial skills.

The author’s 14-year-old mother, Juliana Patience von Kienbusch, holds the 23-pound salmon she caught on the Patapedia River on June 15, 1940. Photo courtesy the authorThe trip represented something of a nod to personal history. My grandfather, Carl Otto von Kienbusch, from whom I got part of my name, was a flyfishing devotee. Each summer he would lease a section of the Patapedia River in Quebec, take the train from Penn Station north, and set up camp in a houseboat. Looking at photos of my teenage mother holding a salmon almost as long as she was tall my admiration grew for her piscatorial skills.

Fly fishing, I quickly learned, is addictive—and an art. My fellow travelers helped refine my technique while sharing flies, and by the end of the trip I was feeling pretty sure of myself—and had caught my first brookie, a small wondrous fish. My new appreciation led me to visit the American Museum of Fly Fishing in Manchester, Vermont, where I found, inscribed in a brick in the walkway, that famous line from Norman MacLean’s A River Runs Through It: “I am haunted by waters.”

The Allagash trip was haunted by memories of Paul Haertel, a member of this cohort who had passed away a few weeks earlier from cancer. Former superintendent of Acadia National Park—and an outdoorsman of the first rank—he had found comfort and joy on the Allagash and a special camaraderie. Fond memories of him came up at every campfire.

Looking back on the trip, certain pictures come to mind: Crikelair at the picnic table reading Henry Adams, not the least perturbed by bugs (there were a few); Beard preparing another gourmet dinner; Koffman reeling in a prize trout; Greg Veilleux describing a moose hunt; and, best of all, Andrew Veilleux announcing he was to be a dad.

Many people over the years have fought hard to keep the Allagash Wilderness Waterway as wild as possible. I thank them all with all my heart.

✮

The author wearing a bug veil to protect against some of the Allagash’s less wonderful wildlife.Carl Little received a lifetime achievement award for art writing from the Dorothea and Leo Rabkin Foundation in 2021.

The author wearing a bug veil to protect against some of the Allagash’s less wonderful wildlife.Carl Little received a lifetime achievement award for art writing from the Dorothea and Leo Rabkin Foundation in 2021.