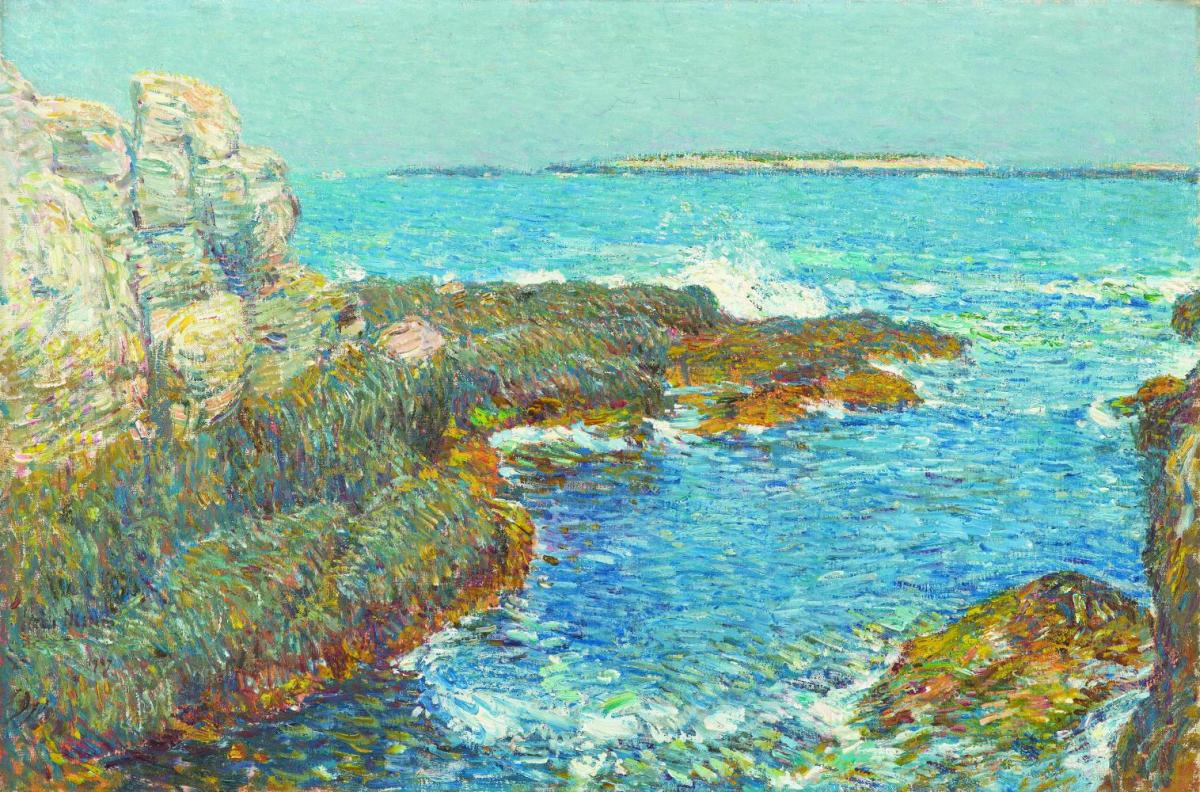

Childe Hassam rendered the eastern end of Sylph’s Rock on Appledore with flurries of brushstrokes in the 1907 Isles of Shoals. Childe Hassam. Isles of Shoals, 1907. Oil on canvas. North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh. Promised gift of Ann and Jim Goodnight.

Childe Hassam rendered the eastern end of Sylph’s Rock on Appledore with flurries of brushstrokes in the 1907 Isles of Shoals. Childe Hassam. Isles of Shoals, 1907. Oil on canvas. North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh. Promised gift of Ann and Jim Goodnight.

Childe Hassam painting on Appledore. From The Cruise of Mystery and other Poems by Celia Thaxter, 1888. Courtesy Boston Public Library, Rare Books DepartmentIn her groundbreaking book, Hopper’s Places, art historian Gail Levin tracked down the sources for a number of Edward Hopper’s paintings, photographing them from an angle close to that chosen by the artist. The paintings and corresponding photographs were reproduced side by side. The success of that book led to Marsden Hartley in Bavaria, five years later in 1990. This time Levin sought out the Maine-born modernist’s views in the mountains of the Wetterstein Range.

Childe Hassam painting on Appledore. From The Cruise of Mystery and other Poems by Celia Thaxter, 1888. Courtesy Boston Public Library, Rare Books DepartmentIn her groundbreaking book, Hopper’s Places, art historian Gail Levin tracked down the sources for a number of Edward Hopper’s paintings, photographing them from an angle close to that chosen by the artist. The paintings and corresponding photographs were reproduced side by side. The success of that book led to Marsden Hartley in Bavaria, five years later in 1990. This time Levin sought out the Maine-born modernist’s views in the mountains of the Wetterstein Range.

These presentations were a clever way to revisit the work of these famous painters; they were also enlightening. One could see how the artist had transformed a particular subject, be it a mansard-roofed Second Empire house on a back street in Rockland, Maine, in Hopper’s case, or a prominent peak in the Bavarian Alps in Hartley’s.

The organizers of the stunning exhibition “American Impressionist Childe Hassam and the Isles of Shoals,” currently at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts, took a similar route. With a much smaller area to cover—Appledore Island is only 95 acres—the curators were able to match nearly every one of Hassam’s motifs with the site that inspired it.

What was this well-known painter doing on this small island seven or so miles off the Maine-New Hampshire coast? Trained in Boston and Paris and later a resident of New York City, Hassam (1859-1935), like many of his peers, sought respite from the summer heat and hurly-burly of urban life. “They must have sea-room,” his Appledore host, poet Celia Thaxter, commented on visitors who chose to put up their feet at this New England watering hole.

The impressionist responded to his island surroundings at all times of day and night. Childe Hassam. Moonlight, 1892. Oil on canvas. Private collection. Photograph by Alex Jamison.

The impressionist responded to his island surroundings at all times of day and night. Childe Hassam. Moonlight, 1892. Oil on canvas. Private collection. Photograph by Alex Jamison.

While Hassam’s excursions to the Isles of Shoals, and to Gloucester, Old Lyme, and other northeastern coastal destinations, were opportunities to take the waters, they also provided the inspiration for some of his finest landscapes. These were working holidays: up at dawn to catch a sunrise, on the rocks in the afternoon to sketch the rocks, on the porch of the Appledore House after dinner to render a sailboat against a blazing sunset.

An afternoon outing to Appledore this past May provided first-hand confirmation of how, even in the throes of his impressionism, Hassam maintained a fealty to the landscape. Led by Jennifer Seavey, director of the Shoals Marine Lab, we visited many of the painter’s favorite motifs, from Babb’s Rock and Broad Cove to the more imaginatively named Devil’s Dance Floor and Broadway and 42nd.

In the course of the tour we learned that the landscape had changed little since the painter’s day, when sporting a beret, the nattily dressed artist would set up a small portable easel and folding chair to work en plein air. Yes, the residents of the island have shifted from rusticators to ecologists—and been joined by black-backed and herring gulls, which were once banished but now nest across the island. Yet the geological essence of Appledore—the trap dykes, granite ledges, fissures, and busted scree—remain unchanged.

Morning, Isles of Shoals speaks to Hassam’s love of Appledore “even though the island is behind us and all we see is an archipelago of sea rocks, the Isles in miniature.”—Curator John Coffey. Childe Hassam. Morning, Isles of Shoals, 1890. Oil on canvas. North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh. Promised gift of Ann and Jim Goodnight.

Morning, Isles of Shoals speaks to Hassam’s love of Appledore “even though the island is behind us and all we see is an archipelago of sea rocks, the Isles in miniature.”—Curator John Coffey. Childe Hassam. Morning, Isles of Shoals, 1890. Oil on canvas. North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh. Promised gift of Ann and Jim Goodnight.

John Rewald, the great authority on French Impressionism, “surreptitiously cut off tree branches” in order to “liberate” some of Cézanne’s views while researching the sites of some of the master’s paintings near Aix in southern France, according to Levin. The admirers of Hassam’s Appledore motifs might feel a similar desire, faced with the foliage that has been allowed to overtake the island and, in some cases, obscure the views.

The Shoals Marine Lab has made one exception to its hands-off-the-flora philosophy: a thicket of staghorn sumac that forms a wall in front of one of Hassam’s most famous island subjects, Babb’s Rock, is cut back from time to time to free up the scene. The sumac has its own beauty and utility: birds nest in it, bees and butterflies visit its flowers, and its hardy nature is a boon to habitat restoration and soil erosion control. Yet the cultural caretakers realize it will grow back, sending its antler-like branches up into the air.

The trip to Appledore fulfilled a long-time desire to visit the place that inspired some of Hassam’s most beautiful and pure landscapes. Here was the rocky world to which the renowned impressionist committed himself from the mid-1880s to about 1916, creating 250-300 oils, watercolors, pastels, and colored pencil drawings—around 10 percent of his overall output.

Among our stops was the garden of the aforementioned Celia Thaxter, who held court over a salon of sorts that included eminent writers, musicians, and artists. Her cottage burned to the ground in 1914, but the garden has been resurrected following the plan that appears in her classic An Island Garden (1894), for which Hassam provided the illustrations.

In her book, Thaxter related the trials and joys of gardening, from importing toads to eat the dastardly slugs, to the glories of her plantings. Those glories are captured in a number of Hassam’s paintings. The loose dynamic brushstrokes he employed in The Island Garden, a watercolor from 1892, seem the perfect means to express the freedom of Thaxter’s horticultural arrangements, where flowers were allowed to overflow the confines of their beds and spread their colors across the nearby landscape.

“Nothing takes color so beautifully as the bleached granite,” Thaxter wrote in Among the Isles of Shoals (1873), an observation borne out in many of Hassam’s paintings of the rocky edges of Appledore. He often focused on those “bare, bleak rocks,” rendering them with the confidence of a consummate impressionist. Viewed from afar, the ledges and shingle in a painting like Isles of Shoals, Broad Cove, 1912, coalesce into a shimmering prospect.

The poppies that spread beyond Celia Thaxter’s garden were a favorite subject for Hassam, seen here in Poppies, Isles of Shoals (detail). Childe Hassam. Poppies, Isles of Shoals, 1891. Oil on canvas. National Gallery of Art, Washington. Gift of Margaret and Raymond Horowitz. Image courtesy National Gallery of Art.

The poppies that spread beyond Celia Thaxter’s garden were a favorite subject for Hassam, seen here in Poppies, Isles of Shoals (detail). Childe Hassam. Poppies, Isles of Shoals, 1891. Oil on canvas. National Gallery of Art, Washington. Gift of Margaret and Raymond Horowitz. Image courtesy National Gallery of Art.

Hassam felt equally comfortable painting the irregular ledges of Appledore and the flag-festooned avenues of New York City. In each place he welcomed the challenge of recreating the scene. “The true impressionism,” he once wrote, “is realism.”

Among the most unusual of Hassam’s Appledore paintings is Jelly Fish, 1912, from the Wichita Art Museum. The dark blue waters off the rocky edge of the island are accented with small circles of glowing white. Thaxter numbered these creatures among the most beautiful elements of her island milieu. “[T]he wonderful jelly-fish,” she wrote, “spreads its large diaphanous cup, expanding and contracting as it swims, and [is] colored like a great melting opal in the pale-green, translucent water.”

Hassam shared an aesthetic kinship with fellow American painter James McNeil Whistler, in particular the latter’s tonalist work, notes art historian Kathleen Burnside. Hassam’s small sunset studies, some of them painted on the covers of cigar boxes, are dazzling in their light effects and also bring to mind Winslow Homer’s semi-abstract watercolors from his summer sojourn on Ten Pound Island off Gloucester in 1880.

The Peabody exhibition includes a series of black-and-white photographs of Appledore by Alexandra de Steiguer, who has served as winter caretaker of the Star Island Family Conference and Retreat Center for the past 19 years. Her photo-essay offers a striking contrast to Hassam’s paintings—a kind of visual counterpoint to the impressionist’s richly rendered landscapes. (He could, wrote curators John Coffey and Hal Weeks, “turn up the volume” on the “natural hues.”)

A line in de Steiguer’s statement that accompanies the photographs underscores the unchanging quality of the island. “As I stand upon this far shore among rocks and vistas that have changed so little as to appear almost timeless,” the photographer mused, “I can’t help thinking that, ultimately, it is this place that bears witness to us.”

Carl Little’s most recent book, Wendy Turner—Island Light, was published by Portsmouth Marine Society.

For More Information

“American Impressionist Childe Hassam and the Isles of Shoals” was co-organized by the North Carolina Museum of Art and the Peabody Essex Museum, where it runs through November 6, 2016. FMI: www.pem.org