It’s rare these days (except when on vacation) that I read a book straight through, cover to cover, but I did just that with Susan Hand Shetterly’s Settled in the Wild. It’s not that this is an inconsequential volume, far from it. Rather, this is one of those rare books worthy of a total immersion. What gives a series of loosely connected essays about life in rural coastal Maine such strength? First, the writing is top-notch: crafted with care, elegant, lean. The author’s is a Maine voice we have not heard often enough, despite Shetterly’s long tenure in the state. Second, while Shetterly writes about a rural lifestyle devoid of “mod cons,” she doesn’t seem to expect extra credit for it. She moved to a cabin in the woods with her husband as part of the wave of 1960s back-to-the-landers who came to Maine in search of a different life. They settled in a simple cabin, presumably grew their food, and reared their children, a lifestyle that ensured them lots of contact with the natural world. Along the way, Shetterly became a wildlife rehabilitator, almost by chance. She writes about this life, sometimes in sharp detail, but spares us the kind of posturing—“Hey, look at me, I have lived off the grid!”—that I find so tiresome. Third, the writing is honest and open, and filled with lovely imagery. Shetterly’s connection to the natural world is strong, intimate, practical, and, most of all, respectful—honed by 30-plus years of careful observation. While living close to the land allowed for keen observation, it can’t have been all roses. Eventually, there was a divorce. Her brief description of that tells us all that we really need to know: “Couples who thought they held the same values, who thought they loved each other, found that under the pressure of living hard and close and often poor, they did not, and filed for divorce. My husband and I were among them.” She has pared to the core what must have been painful and difficult, and has given us the briefest of glimpses. Another writer might have seized the opportunity to invite us into her personal wallow, which would have resulted in a completely different book. The wild creatures of Shetterly’s world have troubles, too. Throughout the book, she does what she can for them, then mostly sets them free to live and die on their own wild terms. In one amazing chapter, she saves a young rabbit from a bobcat—face to face with a bobcat!—then returns the rabbit to the wild to fend for itself when she realizes that its chances are probably just as good without her as they would be with. Baby bunnies aside, Shetterly doesn’t write just about the pretty critters. The hummingbirds that arrive from their long migration are described in all their glory, but so are the shining alewives and slippery elvers upon their arrival. White tail deer, raptors, and corvids, even cormorants, are described with care; her facts about all of them are both interesting, and, as far as I can tell, spot on. I grew up in Maine, and thought I knew a lot about our creatures, but I learned more from this book. Shetterly’s practical point of view extends to death. I can think of few writers who could describe maggots devouring the carcass of a road-killed deer in language of such sheer clarity that the reader finds little time to be disgusted by the scene. Lest you be more squeamish than I, I’ll share only the ending: “The deer gave itself to the task of becoming something else, which did not look either easy or painful. Some days later, it flew away as blowflies and flesh flies and carrion beetles.” Another example of Shetterly’s evocative way with words crops up in an essay on Maine’s reintroduced wild turkeys. She writes: “Once when I was out walking the Sopkin woods road in high summer, I watched a mother turkey swirl her big wings around her chicks to protect them from my approach, and the gesture, touching and vulnerable, has stayed with me.” It has stayed with me as well. Settled in the Wild is primarily a book about the wild world, but a central theme is the challenges raised when the lives of humans and wild animals intersect. Shetterly is well aware that we are animals, too, and fallible ones at that. In our attempts to save nature from ourselves, we sometimes do more harm than good. She doesn’t shy away from telling us about her own mistakes, as a way to illustrate that the real world has hard lessons to teach even those who dive in with the best of intentions. Sometimes (remember the bunny) left alone is well enough. Shetterly is in a class with some of our best nature writers: Rick Bass and Terry Tempest Williams come to mind. On second thought, she is in a class with some of our best writers, period. Thinking close to home, I expect that E.B. White would have enjoyed this book. He certainly would have admired the spare beauty of her writing. My only criticism is that I found Settled in the Wild to be too short. I reached the end and wanted more. I am already planning my next immersion—this is a book to be read, and then read again. If Susan Hand Shetterly writes another book (and I hope she does) I expect that I will read that one straight through as well, whether I’m on vacation or not.

—Gretchen Piston Ogden

Magazine Issue #

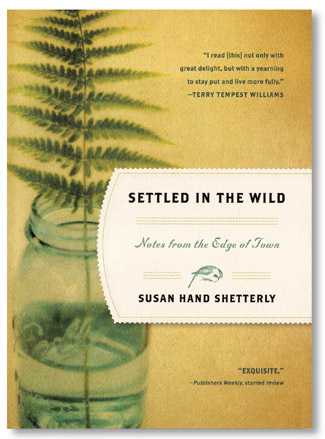

Display Title

Book Review: Settled in the Wild

Secondary Title Text

Notes from the Edge of Town

Sections