Illustrations By Richard King

One weekday morning in August, a 19-foot Carolina skiff buzzes into the cove between Martin’s Point and Mackworth Island, just beyond Portland. Kelsey Berger, a recent graduate of Bowdoin College, sits with one hand steadying a huge plastic tub.

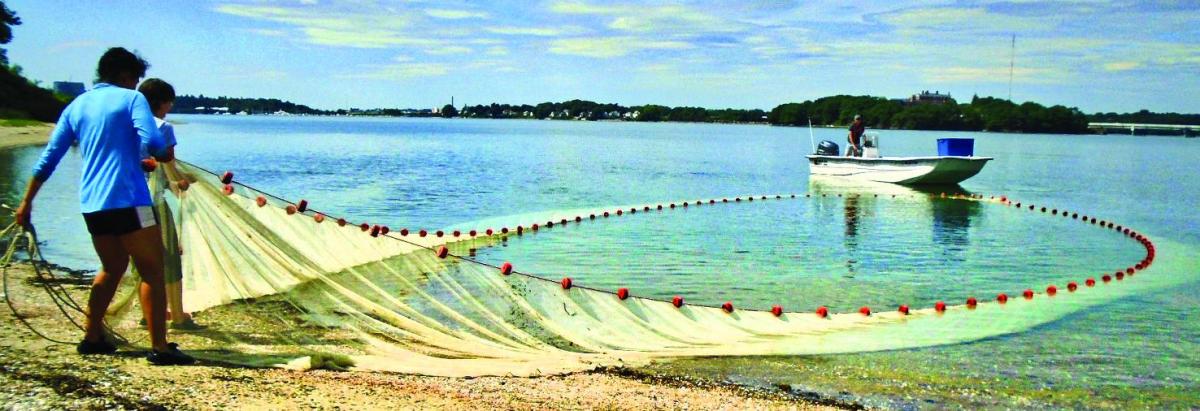

The cove has a hard triangular shape, with a highway on one side and on the other a rip-rap causeway that connects Mackworth Island to the mainland. Two small families have just set up their chairs on the beach by the causeway. But the people do not turn to look as the driver coasts the boat to the sand so Kelsey can jump off. She holds on to one end of a net as it draws out of the tub, while Vanessa, another intern and a graduate student at the University of Southern Maine, feeds the rest into the water. The driver reverses and then bends back to shore so that their 150-foot seine sets in a wide arc. Vanessa steps off onto the sand beside Kelsey and the two of them begin to haul it back in.

Photo by Richard King

Photo by Richard King

I offer to help, to which Kelsey replies that it’s better if just one person is on each side, “so the net comes up evenly.”

“Maybe I could sing a seine-hauling chantey,” I say. “I have a favorite called Catch it, Oh! And ’Round the Horn!”

Kelsey smiles in the kind way that respectful young people do when bothered by middle-aged men who fancy themselves with a clever wit.

“I can’t imagine you’re going to catch much here,” I add.

“You’ll be surprised,” she says, still hauling.

Kelsey Berger was a research intern last summer for the Casco Bay Aquatic System Survey, developed and run by the Gulf of Maine Research Institute (GMRI). For nearly 50 years, GMRI has been working to build our knowledge of local waters through research and through outreach. You’d never know it driving by—their building is on Commercial Street in downtown Portland—but the institute hums all year with over a dozen long-term research programs and a network of dynamic and enthusiastic educational and community programs. GMRI’s mission is exemplified by this wide-ranging, long-term Casco Bay Aquatic System Survey, known as CBASS. The survey is establishing a baseline during this rapidly shifting age of anthropogenic climate change to benefit fishermen, coastal managers, ecologists—and you.

The boat driver, Adam Baukus, a long-time research associate with GMRI, secures the boat and comes in to help sift through a flittering catch of dozens of Atlantic silversides, mummichogs, and hermit crabs. While Vanessa and Adam sift, measure, and identify the catch with their fingers, measuring boards, and pasta strainers—occasionally tossing a small invertebrate back into the water—Kelsey records everything. In the net they find several juvenile winter flounder, a species of which they’d seen more than usual this summer, including one in this haul that is nearly four inches long. They find so many European green crabs, an introduced species first observed in Casco Bay in 1904, that Kelsey declares over her clipboard, “This is green crab city.”

Once they have hauled in the beach seine at Mackworth Island (top of page), the GMRI researchers sort, measure, and record the catch (bottom image). Photo by Richard King

Once they have hauled in the beach seine at Mackworth Island (top of page), the GMRI researchers sort, measure, and record the catch (bottom image). Photo by Richard King

The research team counts and measures every fish and crustacean caught in the seine. Into vials and plastic bags they place up to 25 of each fish species and a tissue sample (such as a leg) from five crabs. These all go into a cooler to take back to the lab where in the weeks and months ahead they will dissect out the fishes’ otoliths—the bones of the inner ear—in order to determine the age of the individuals. Then they’ll grind up each fish and crab to insert in an instrument called a “bomb calorimeter.” This gives them information about the energy that these prey species provide and how these calories might travel through the food web to larger predators in Casco Bay and beyond.

Kelsey has a particular passion for data. She likes compiling and manipulating and analyzing numbers. In the final intern presentations just the day before, she had explained the findings so far of the summer beach seine collections. She investigated fish movement by species in particular and how it changed over the course of the season. She examined how the data varied among their 12 seining sites—such as this sandy beach at Mackworth, the mudflat at Mussel Cove, the shell hash and sand bottom at The Brothers Island, and the brackish water at Presumpscot moorings.

Dr. Graham Sherwood and his GMRI colleagues who designed CBASS are interested in how all of these variables might attract and support different prey fish and invertebrates as well as juveniles of larger fish and crustaceans of commercial value. The researchers have regularly found four primary fish prey species in the nets. Silversides are by far the most consistent, followed by mummichogs, alewives, and Atlantic herring, with the latter two less common later in the summer. Kelsey and the other researchers are also curious, for example, to see if the amount of winter flounder this year will continue or was, well, a fluke. (The stand-by fish puns don’t get old at GMRI. They’ve named their Carolina skiff Havin’ Fundulus II, since fundulus is the genus name for the mummichog. And when the scientists “landed” on the title and acronym of CBASS for this survey, there was an outsized celebration.)

This cartoon shows the most common species caught in beach seines around Casco Bay.

This cartoon shows the most common species caught in beach seines around Casco Bay.

Kelsey, Vanessa, and Adam pile the net in the tub, clean up the beach, and record the water temperature, the salinity, and other measurables. Then they push off for the next sampling site. This has been their fourth of six sites for the day, racing against what they can do on a given tide. They also need to record and release the catch in their lobster pots.

As Adam pilots the boat and takes a swig from his water bottle, Kelsey pulls out a slice of pizza.

The longhorn sculpin was caught during a jigging survey out in Casco Bay. Photo courtesy GMRI“I feel like I never had a concept,” she explains, “that when I went to the beach I’m scaring away that many fish, that many crabs. And shrimp. We didn’t have any just there, but sometimes there’s a bazillion shrimp! I just had no concept how much life there is, because I couldn’t see it. I would’ve thought a typical Maine beach would just have some eelgrass, some seaweed beneath the tide, but it’s really teeming with life.”

The longhorn sculpin was caught during a jigging survey out in Casco Bay. Photo courtesy GMRI“I feel like I never had a concept,” she explains, “that when I went to the beach I’m scaring away that many fish, that many crabs. And shrimp. We didn’t have any just there, but sometimes there’s a bazillion shrimp! I just had no concept how much life there is, because I couldn’t see it. I would’ve thought a typical Maine beach would just have some eelgrass, some seaweed beneath the tide, but it’s really teeming with life.”

At Mussel Cove, they begin pulling up one of their lobster traps when Adam sees in the distance a shallow swirling in the water. It’s a school of menhaden. The dark whirlpool moves closer. Now with the right light angling under the surface, the three researchers gape at a glorious, shimmering, circling bronze-black cloud in which individual scattered fish flash over in turn to reveal their sparkling silver bellies. Kelsey leans over the rail with her mouth open.

Until she has to finish writing down the carapace lengths of the lobster.

This stickleback was caught in a beach seine. Photo courtesy GMRIThe beach seine is just one of five components of the Casco Bay Aquatic Systems Survey, all of which will be regularly conducted over the decade between 2014 and 2024. For the second component, Adam, a new set of interns each summer, and other members of the GMRI research staff collect near-shore groundfish species for the “jigging survey,” meaning they put down fishing lines at 20 different sites. The third activity is the “plankton survey” as part of the deeper water oceanographic sampling. On a larger boat farther off the coast, they deploy fine mesh nets to determine the concentrations, migrations, and types of microscopic plants and animal-life that form the base of the Casco Bay food webs. The fourth CBASS research component is the “acoustics survey,” during which they submerge a high-tech transducer with multiple frequencies that records over a 45-mile-long track a sonar picture of the water column and the bottom, helping researchers identify what’s there, whether a school of pollock or herring, or a muddy bottom instead of a sandy one.

This stickleback was caught in a beach seine. Photo courtesy GMRIThe beach seine is just one of five components of the Casco Bay Aquatic Systems Survey, all of which will be regularly conducted over the decade between 2014 and 2024. For the second component, Adam, a new set of interns each summer, and other members of the GMRI research staff collect near-shore groundfish species for the “jigging survey,” meaning they put down fishing lines at 20 different sites. The third activity is the “plankton survey” as part of the deeper water oceanographic sampling. On a larger boat farther off the coast, they deploy fine mesh nets to determine the concentrations, migrations, and types of microscopic plants and animal-life that form the base of the Casco Bay food webs. The fourth CBASS research component is the “acoustics survey,” during which they submerge a high-tech transducer with multiple frequencies that records over a 45-mile-long track a sonar picture of the water column and the bottom, helping researchers identify what’s there, whether a school of pollock or herring, or a muddy bottom instead of a sandy one.

A diagram of the monitoring sites. Courtesy Gulf of Maine Research Institute

A diagram of the monitoring sites. Courtesy Gulf of Maine Research Institute

The fifth and last component of CBASS is the “river sampling” of fish and water conditions as far up as the Presumpscot River Falls. This river is the largest source of fresh water to Casco Bay. It’s been dammed at several places since the 1730s, at times controversially. So the passage of any alewife and salmonids is of special interest, especially as proposals for dam removal progress.

So Kelsey’s beach seine site at Mackworth is an especially compelling place, because it’s right at the mouth of an estuary busy with fish migrating up and down and only a couple miles from free-flowing ocean water in Casco Bay and the open Gulf of Maine. Kelsey did not record any juvenile alewife in the beach seine this particular morning, but the team did earlier in the year.

When Kelsey, Vanessa, and Adam finish sampling, they’re far from done. Under Adam’s direction, they haul the boat and drive it on a trailer to the GMRI building, where they bring the samples into the lab, hose down the skiff, and spread the net out on the lawn to dry. Adam, a scientist himself, operates as a first mate to the principal scientists of the CBASS project. In other words, Adam makes everything happen.

Kelsey has only one more day of her summer at GMRI. Adam and the other year-round staff will continue the sampling during the autumn until the weather becomes too much for their small research fleet. Over the winter and spring they will continue processing, analyzing, and publishing in scientific journals and on their public website at www.gmri.org. Then next summer they’ll be ready to repeat it all with a new group of interns.

“I think it’s cool that it’s ongoing,” Kelsey says. “To get people tapped into what is happening in the water.… A lot of the sites, like that beach at Mackworth, you can see from just walking around Portland’s east end.”

“Before this summer,” Kelsey continues, “I didn’t know that much about fish ecology. I’ve enjoyed learning about what kind of fish people are using for bait, and which we catch to eat. What’s marketable. In the GMRI lunchroom they’ve always got the newspaper and updates on what fisheries are open, what’s closed, where fish are appearing, and where they haven’t normally shown up.”

GMRI seems unique, she says, because it taps into Maine’s cultural heritage as well as the scientific community. “It’s just, well, GMRI is doing a lot as an organization. Even when I applied for this internship, I didn’t quite grasp how much was even going on here.”

Overlooking Portland Harbor under GMRI’s sign with its official mission, “Science—Education—Community,” Kelsey sits down with Vanessa and Adam for lunch, which because of how full the morning has been is now closer to an early dinner. They’re still talking about the school of menhaden.

“That’s what I like about this monitoring program,” Adam says. “We’re out on Casco Bay so much. Enough so that we know what to expect, know what’s there. So when something is out of the ordinary you notice it.”

With this one example, Adam ends up summarizing what GMRI hopes to do to improve life in coastal Maine. The organization works alongside fishermen and government agencies and the broader public, while giving young people like Kelsey enormous opportunities.

“We might not have otherwise noticed that swirl in the water,” Adam says. “Those fish don’t always migrate this far north. Menhaden are prey fish—similar to herring, but bigger, beefier, oilier. They draw a different suite of predators. There are large fishing boats like that blue one right over there—the Ruth and Pat, about 100 feet long—and this summer it fished right behind Mackworth Island after menhaden for lobster bait.”

“The state has been working to adjust new rules for fishing menhaden, which do not normally come this far north,” he says. “This year, maybe because of seawater temperature shifts, they were in Casco Bay in big numbers. And we don’t know much about their ecology here. But we’ll all know more in a few years.”

Richard J. King is the author of Lobster and The Devil’s Cormorant: A Natural History. He is a research associate with the Maritime Studies Program of Williams College and Mystic Seaport.

For More Information:

Gulf of Maine Research Institute

350 Commercial St.

Portland, ME 04101

207-772-2321 | www.gmri.org