On peaceful walks in the Wells Reserve, where trails lead from a restored 19th-century saltwater farm to gentle meadows and the shore, I’ve photographed textured landscapes of salt marsh and upland fields, and spied on piping plovers enjoying the sand beach. I’ve inhaled sweet and pungent scents. My mind has wandered freely, unhurried, the quiet broken only by the brush of wind, bird song, and rolling waves. That was before I discovered that the Wells National Estuarine Research Reserve has a busy double life.

Located half way between Portland and Portsmouth, the town of Wells is home to the only National Estuarine Research Reserve in Maine. Its 2,250 acres include seven miles of interpretive trails that are open to the public year-round. But this seemingly tranquil sanctuary is also an active hub for learning. Visiting scientists join staff researchers at the Maine Coastal Ecology Center to study biodiversity, coastal ecology, and climate change in watersheds throughout southern Maine. Educators and volunteers annually conduct more than 100 classes for people of all ages. Community leaders meet here to plan for weather-related emergencies and collaborate to conserve natural resources. Annual craft and music festivals and frequent guided bird walks attract people from afar. And here, too, history is preserved, because an historic farm, Laudholm, is now the site of today’s reserve.

When people think of marine biology in Maine, they generally think of whales, cod, haddock, and other commercial fisheries. Yet estuaries such as the one above are hugely important to how those offshore systems function. Courtesy Laudholm Farms

When people think of marine biology in Maine, they generally think of whales, cod, haddock, and other commercial fisheries. Yet estuaries such as the one above are hugely important to how those offshore systems function. Courtesy Laudholm Farms

First settled for farming in 1643, the property was worked continuously by successive owners for more than 300 years. Soon after being named Laudholm Farms in 1908, it grew to be the largest saltwater farm in York County. It supplied milk, cream, butter, eggs, and broilers to the Wells community and sent products weekly to Boston. But the farming operation gradually declined and some buildings fell into disuse. In 1978, local citizens formed a trust to save the historic property on which developers were planning to build single-family homes. By then, most of the farm buildings were structurally sound but neglected, the silo was beyond repair, and the water tower had no tank.

After several years of fund-raising, the group had enough money to purchase the land. Then came news that the Maine State Planning Office had received word from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) that the National Estuarine Sanctuary system was looking for a site in Maine. The town of Wells expressed interest and joined forces with the Laudholm preservationists. The save-the-farm focus shifted to a wider purpose with multiple partners.

Now on the National Register of Historic Places, Laudholm is no longer a working farm. But as headquarters of the Wells National Estuarine Research Reserve at Laudholm, its legacy is guiding us to a healthier environment and wiser use of Maine’s coastal resources.

Photo by Janet Mendelsohn

Photo by Janet Mendelsohn

Estuaries are where rivers meet the sea, mixing fresh water with salt. These amazingly productive ecosystems provide habitat for an absorbing array of plant and animal life, they filter pollutants from water before it reaches the sea, and they act as buffers against coastal storms.

Of the 28 National Estuarine Research Reserves in the United States, from Alaska to the Great Lakes and Puerto Rico, all are partnerships between the federal government and coastal states. The Wells Reserve is overseen by a state entity (Wells Reserve Management Authority) and funded largely by NOAA (federal) and the private, nonprofit, “state” partner, Laudholm Trust. This public-private funding relationship is unique within the reserve system. The trust and NOAA account for most of its budget. Additional major partners are the Town of Wells; the Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry; and the USFWS Rachel Carson National Wildlife Refuge. Several universities and smaller entities participate to a lesser extent.

Collecting data on the Mousam River. Courtesy Jeremy MillerCurious to learn more about what happens off the trails, I arranged to meet some of the folks in charge at the Wells Reserve. In the Maine Coastal Ecology Center (a part of the reserve), Research Associate Jeremy Miller and his colleagues focus on how changes in adjacent land use, as well as in such physical and environmental variables as climate change and sea level rise, affect the ecology and function of estuaries.

Collecting data on the Mousam River. Courtesy Jeremy MillerCurious to learn more about what happens off the trails, I arranged to meet some of the folks in charge at the Wells Reserve. In the Maine Coastal Ecology Center (a part of the reserve), Research Associate Jeremy Miller and his colleagues focus on how changes in adjacent land use, as well as in such physical and environmental variables as climate change and sea level rise, affect the ecology and function of estuaries.

Despite the importance of estuaries as coastal buffers and the natural beauty that they hold, Miller said, they are an understudied part of our natural world. When people think of marine biology in Maine, they generally think of whales, cod, haddock, and other commercial fisheries, yet estuaries are hugely important to how those offshore systems function. Estuaries act as filters, habitats, nurseries, and feeding grounds for many species of commercial importance. Miller manages the System Wide Monitoring Program, a core element of the Wells Reserve’s effort to collect data on water quality, weather, and nutrients. The data contributes to a nationwide monitoring system maintained by all 28 estuarine reserves.

“We have a lot of visiting researchers who come with many different outlooks, some studying plants or fish or mammals,” Miller said. “This long-term monitoring data gives them a good background for comparing change. Someone studying fish in the river, for example, can get water quality information going back to 1995. They’re just blown away by the fact that we have monitoring data going back that far. The data can sometimes help to explain what they’re seeing in the estuary. It lays a good groundwork of environmental data they can reference or learn from.”

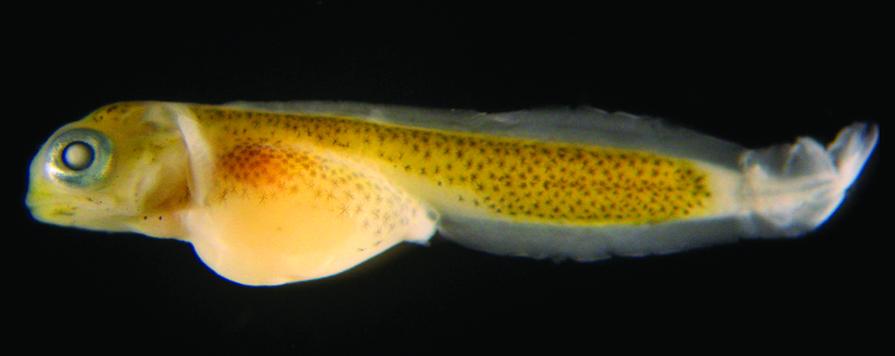

Among other tasks, Miller and his associates monitor larval fish. In this early life stage, when the fish hatch from their eggs and are actually part of the plankton, moving with the tides, they become food for other species as they transition into the juvenile stage. “We found cod and three species of flounder in our estuary, and a lot of migratory fish, like herring, that are bait fish in the marsh,” Miller said. “Nutrients we see in the water often drive the biological component. Fish can’t live where the water isn’t suitable for them because of low oxygen or particles suspended in the water.”

Miller also coordinates local volunteers for MIMIC, the Marine Invader Monitoring and Information Collaborative, run and funded by the Coastal Zone Management Program in Boston, keeping tabs on marine invasive species in the Gulf of Maine. Once a month, the Wells MIMIC team monitors docks, tidal pools, and intertidal habitats from York Harbor to South Portland. Invasive species, introduced by ballast-water discharge from ships traveling from international ports, the fouled hulls of recreational boats, and, to a lesser extent, the release of exotic pet fish and crabs, compete with native species and sometimes foul commercial fishing gear.

“Invasive species are wreaking havoc on a lot of fisheries, particularly aquaculture,” said Miller. “My best example is the mussels farmed on Prince Edward Island, all of which are farmed on big ropes. Invasives are settling onto those same ropes, adding too much weight, and the ropes are snapping.”

Research loses its relevance if it’s not shared. Wells Reserve Director Paul Dest oversees a year-round staff of 14 that doubles in number when interns, post-doctoral fellows, and graduate students arrive in the warm months. Dest said their diverse activities are community focused and that partnerships are a hallmark of the Wells Reserve. He singled out the reserve’s Coastal Training Program as an example of community orientation.

The Coastal Training Program is led by educator Dr. Christine Feurt, who said the program puts science into the hands and minds of decision-makers, including state officials, harbormasters, clam wardens, and local planning boards. The goal is to get everyone to think cumulatively rather than narrowly about impact on their own area of responsibility.

Among hot-button issues addressed in CTP workshops is shoreline zoning. “Even though people are bound to enforce the Clean Water Protection Act,” Feurt said, “they often don’t see what they’re doing that way. If the shoreline buffer is left alone, it has the ability to filter out pollution at no cost, but if we’re talking about your house, you may just want the view.”

Larval fish, fresh from the egg, are an important part of the estuarine food chain. Courtesy Jeremy Miller.

Larval fish, fresh from the egg, are an important part of the estuarine food chain. Courtesy Jeremy Miller.

A series of boat trips, called “We’re All in the Same Boat,” is proving to be an effective tool to open the eyes of community leaders. The excursions are part of a five-year project with the University of New Hampshire. Groups venture out on the Saco or Salmon Falls rivers with Jeremy Miller at the helm. Dialogue is redirected as participants literally look at the estuary shoreline differently from the way they view it from land.

“Wells Reserve is surrounded by experts,” Feurt said, “so we create a space to talk about the issues people are wrestling with.” In addition to clean-water protection and storm-water management, the conversation includes such subjects as woodlot management and chemical-free lawns that limit runoff’s affect on the environment for lobsters, among other inhabitants. Of the more than 400 bird species known to come to Maine, 122 visit the Saco River estuary. The marsh is also a nursery for some 20 species of fish.

Reserve director Paul Dest said the general public has become more aware of the watershed’s importance as global warming puts greater demands on shoreline areas.

The reserve’s research program was founded by Dr. Michele Dionne, who directed the effort for 21 years until her death in 2012. Her signature programs focus on two main waterways: the Little River Estuary, which forms a northern/eastern boundary for the reserve, and the Webhannet River, protected in part by the Rachel Carson NWR but also close to heavily developed tourist areas.

Research scientist Jennifer Dijkstra, who worked alongside Dionne, is advancing what is known about how algae in a salt marsh determine the presence of other plants and animals. Among her experiments has been a series to determine how animals that inhabit the salt marsh use various forms of seaweed habitat for food, shelter from predators and protection from the sun. There are real-world implications for the work. Seaweed (a free-living form of algae) is a harvestable crop used for fertilizer, packing, animal feed and cosmetics. One variety is rockweed, which can be harvested mechanically at a rate of 100,000 pounds per day. In 2010, Maine’s rockweed harvest was 12.7 million pounds. If excessive quantities are improperly removed, the impact can be detrimental to organisms at the salt marsh surface, significantly altering the ecosystem. The marsh is also home to some 20 species of fish.

Photo by Janet Mendelsohn

Photo by Janet Mendelsohn Meanwhile, restoration projects are under way. In the Drakes Island Marsh, a culvert originally allowed tidal waters to flow under Drakes Island Road, keeping salt marsh on both sides relatively healthy. When the culvert collapsed, fresh water dominated the upstream portion of the salt marsh, causing a decline in the marsh’s quality and overall size. Now a new culvert allows the tide to flow properly, improving habitat and helping manage water levels to prevent basement flooding in nearby homes.

Stewardship programs at the reserve also protect and manage habitats and wildlife. There are projects to improve shrubland habitat for cottontails, Maine’s only native rabbit, and thin the local deer population, which is estimated at more than 75 per square mile. Because deer are voracious eaters of native plants and act as hosts for Lyme-disease-carrying ticks during the second year of the tick life cycle, they are of growing concern here and elsewhere.

Nearly 8,000 people of all ages participated in nature programs and workshops at the Wells Reserve during 2011, said Education Director Suzanne Kahn Eder. In addition to bird walks guided by York County Audubon volunteers, there’s a climate-change speaker series that includes discussions of inexpensive ways to be more environmentally responsible. Estuary kayak trips with a Maine Guide are offered from late spring until fall. Year-round, free exhibits and guided tours delve into the history of the saltwater farm, explore biodiversity of the intertidal zone, look for evidence of animal homes, and reveal what’s special about the salt marsh.

Discovery Program backpacks, for children ages 6 to 12, are available for loan. They contain field guides, binoculars, bird identifiers with sound cards, and games to play out on the trails. A new school program, Wild Friends in Wild Places, for school children in grades K-2, in partnership with York’s Center for Wildlife, introduces children to bird and mammal “ambassadors,” whose injuries prevent them from living in the wild; the children are taken out in the field to look for the habitats that wounded kestrels, owls, spotted turtles, bats, and opossums prefer.

A clever Picture Post Project encourages visitors on the trails to hold the back of their digital cameras against each side of an octagonal post, shoot each scene, create a panoramic photo, and upload the photo to a designated website. It’s part of Digital Earth Watch, a collaboration among the University of Southern Maine, the University of New Hampshire, and other partners. The cumulative album chronicles shifting sands and tides at Laudholm Beach, habitat for cottontail rabbits, and seasonal transformation of shrubland and salt marsh.

And then there are the Geographic Information System (GIS) maps, materials, and training services developed at the reserve. The maps and materials are primarily for use by land trusts and conservation commissions; the training is most often offered to municipal officials, storm-water professionals, and others in related fields.

Yes, the Wells Reserve is a busy place, though most of the work there takes place discretely in the background. I felt better about not long ago being ignorant of the reserve’s double life when I met Nik Charov, president of the Laudholm Trust. He said he had no idea the place even existed despite having driven past it while traveling between Peaks Island and New York every summer for 35 years. That changed when he and his wife decided to move their family to Portland.

Charov, an avid outdoorsman, sees his new position as president of the Laudholm Trust as the perfect job. After eight years in New York City working to protect the environment and develop science programs as a fundraiser for both Bette Midler’s New York Restoration Project and the New York Hall of Science, he said the Wells Reserve has captivated him because it engages people with nature through education, art, data, and stewardship.

“It’s off the beaten path and people love how pristine this place is,” said Charov, sitting in his art-filled office. “But there are weddings here almost every weekend all summer and festivals like the annual Laudholm Nature Crafts Festival in September. It’s a great, safe place for kids to run on a clean, protected beach.”

As president of the reserve’s fundraising arm, Charov’s vision is already taking shape. This August, a string quartet will perform at sunset in the barn. In the audience, a birder on his first visit to the reserve might discover that there are guided walks during the fall migration season. In September, at the annual Crafts Festival, a family may decide to return in winter to hike the trails. And on a misty spring morning, a scientist or a writer might wander, as this writer did, immersed in nature’s magic and mysteries.

Contributing Editor Janet Medelsohn can be reached at www.janetmendelsohn.com.

For more information:

Wells National Estuarine

Research Reserve at Laudholm

342 Laudholm Farm Rd., Wells, ME 04090

207-646-1555; www.wellsreserve.org

Trails are open every day. Admission is charged from Memorial Day weekend through Columbus Day, but entry is free for Laudholm Trust members except for special events. Be prepared for ticks and poison ivy (off the trails). The visitor center and restrooms are wheelchair accessible. Some trails are accessible by special arrangement.