Inside the Frame

These artisans lay creative foundations

Photographs by Laurie Schreiber

The people who make the art often get our attention, but who stretches their canvases? Who makes their frames? The husband-and-wife team of Paul Monfredo and Nancy McCormick in Seal Harbor has made a name for themselves producing gorgeous gilded and painted frames—shimmering works of art in gold and translucent tempera. Down the coast in Lincolnville, another team of craftsmen, Chris Polson and Joe Calderwood, has become the go-to point for many well-known artists looking for stretched canvases.

Nancy McCormick works in watercolor and egg tempera, and brings a depth of knowledge about the history of European and American art to her intimate abstract landscapes.

Nancy McCormick works in watercolor and egg tempera, and brings a depth of knowledge about the history of European and American art to her intimate abstract landscapes.

Frame makers add a golden sparkle

Paul Monfredo first learned gilding from a friend, Gene Witten, a painter who lived in upstate New York, and subsequently spent years exploring techniques and materials used in traditional framing.

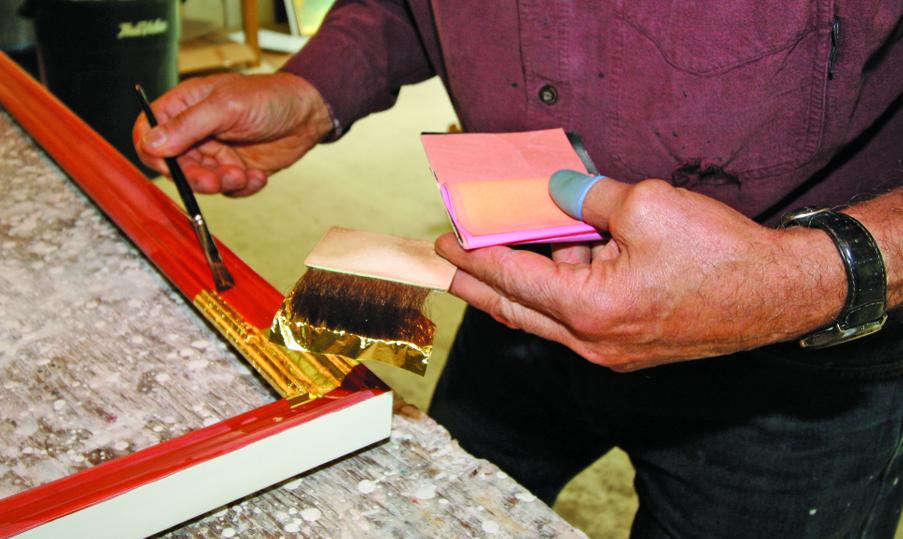

On a recent afternoon, Nancy McCormick and Paul Monfredo were busy in their respective upstairs studio and downstairs workshop in a building next to their home. McCormick, who also paints abstract canvases, was drawing with colored pencils on heavy paper—blues and purples in horizontal strips that seemed to ripple like a light breeze upon a pond’s surface. Monfredo was cutting pieces with his bandsaw for a custom frame that he will afterward treat with special clay and meticulously gild with two-inch-square, tissue-thin pieces of 22-karat gold. This ancient process, called “water gilding,” uses the same materials today as were used hundreds of years ago. Once it is burnished, the clay’s hue emerges behind the gold—the finished effect harks back to decorative styles of old.

Paul Monfredo first learned gilding from a friend, Gene Witten, a painter who lived in upstate New York, and subsequently spent years exploring techniques and materials used in traditional framing.

On a recent afternoon, Nancy McCormick and Paul Monfredo were busy in their respective upstairs studio and downstairs workshop in a building next to their home. McCormick, who also paints abstract canvases, was drawing with colored pencils on heavy paper—blues and purples in horizontal strips that seemed to ripple like a light breeze upon a pond’s surface. Monfredo was cutting pieces with his bandsaw for a custom frame that he will afterward treat with special clay and meticulously gild with two-inch-square, tissue-thin pieces of 22-karat gold. This ancient process, called “water gilding,” uses the same materials today as were used hundreds of years ago. Once it is burnished, the clay’s hue emerges behind the gold—the finished effect harks back to decorative styles of old.

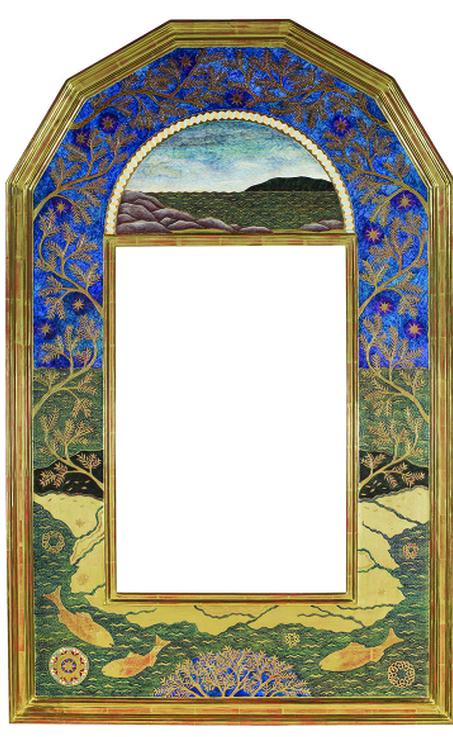

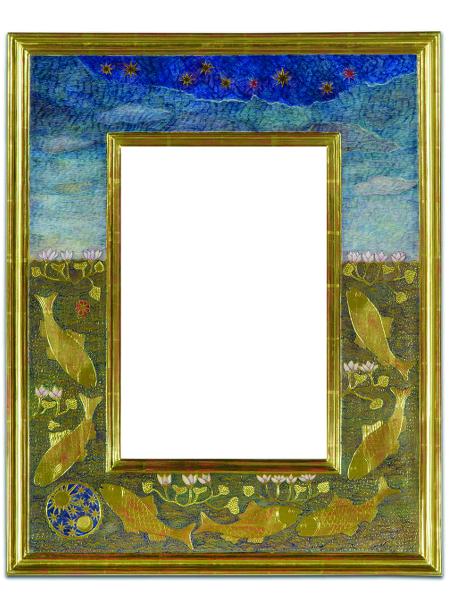

Both of these gilded and painted frames were made for mirrors. Common themes include delicately etched gold fish and coral, cosmology symbols, and flowery vines reminiscent of Renaissance art. Images courtesy Nancy McCormick and Paul Monfredo

The two, who have been married for about three decades, worked separately for years—McCormick painting original works and Monfredo building gilt frames. “Then, at some point, our skills converged,” said Monfredo. “One of my clients wanted a mirror with some images on it, and I thought it would be a prime opportunity to have Nancy introduce some paint to the gilding process.”

Both of these gilded and painted frames were made for mirrors. Common themes include delicately etched gold fish and coral, cosmology symbols, and flowery vines reminiscent of Renaissance art. Images courtesy Nancy McCormick and Paul Monfredo

The two, who have been married for about three decades, worked separately for years—McCormick painting original works and Monfredo building gilt frames. “Then, at some point, our skills converged,” said Monfredo. “One of my clients wanted a mirror with some images on it, and I thought it would be a prime opportunity to have Nancy introduce some paint to the gilding process.”

That was in the late 1980s. Ever since, the two have created dozens of gorgeous mirrors and frames that combine gold leaf and translucent paint. The results, which are reminiscent of medieval panel paintings, meld McCormick’s studies of ornamental design with Monfredo’s talent for hand-crafting museum-quality frames and panels.

The joint process is a strategic combination of their talents. It begins with Monfredo, who produces custom wooden frames and panels, using woods typical for the purpose, such as basswood and poplar. He gradually applies six coats of gesso that he makes himself by mixing animal skin glue and calcium carbonate. The six coats produce a hard, evenly smooth layer.

McCormick develops a design on transfer paper, and then uses a stylus to transfer the design onto Monfredo’s gessoed piece. The design might include gold leaf, paint, or a combination of the two. In the areas that will just be painted, McCormick applies a latex resist to protect the surface.

McCormick develops a design on transfer paper, and then uses a stylus to transfer the design onto Monfredo’s gessoed piece. The design might include gold leaf, paint, or a combination of the two. In the areas that will just be painted, McCormick applies a latex resist to protect the surface.

She then hands the piece back to Monfredo, who applies two or three coats of his hand-mixed “bole,” a type of silky smooth clay used by gilders. Red is the traditional color, but he might instead use yellow, black, or blue. He sands and polishes the clay once it has dried. Then it’s time to apply the gossamer-thin gold leaf. Measuring just one inch by one inch and weighing less than half an ounce, each box of gold leaf contains a thousand leaves, packaged in books of 20 interleaved with tissue. To demonstrate the element’s ephemeral nature in this form, Monfredo rubs a sheet between his hands then pulls his fingers apart: the gold has disappeared.

“Theoretically, pure gold can be one molecule thick and stay together,” Monfredo said.

On a recent afternoon, he was working on a frame for a client’s John James Audubon print. He sluiced a bit of water on a small section of the clay to reactivate the glue. Then he lifted a leaf from its book with a special, flat brush made of squirrel hair.

“Don’t breathe. This will blow away,” he said as he leaned over the frame and “floated” the leaf on the water’s surface. As the water dried, it pulled the leaf down, bonding it to the frame’s surface. “It’s all about control and not having voids, or holidays, as they’re called, in the wrong spot,” Monfredo explained. Once he’s done, he either burnishes the gold with an agate, or rubs and antiques it, depending on the desired finish.

Then it was McCormick’s turn again. She pulled off the resist so she could paint the gessoed surfaces. Sometimes she also paints on the gold-leafed surface. Numerous layers of paint create a luminous effect. Often, she etches tiny designs directly onto the exposed gold, and into the painted-over-gold to reveal ribbons or flecks of gold beneath.

McCormick’s touch is extremely delicate. She uses tiny brushes to create, for example, dozens of tiny petals amidst a field of gold. Several layers of nearly transparent paint allow the element’s beauty to shine through.

“It took a while to learn how to use the paint on top of the gold,” McCormick said. “It’s second nature to me now, but originally I had to do a lot of experimenting.”

The motifs of these pieces are whimsical, reminiscent of folk art and religious motifs around the world. There are fish and curlicue waves, stars and compass roses, trees and petals, suns and moons, clouds floating across the sky. McCormick is constantly in search of new motifs. She’s equally inspired by Italian Renaissance paintings, children’s illustrations, and Asian fiber art.

The two love their work. Both mention how meditative it is—Monfredo, as he meticulously applies each leaf; McCormick, while she leans in to accomplish the nuanced details of the design.

“I love the little tiny brushstrokes and the transparency of all the materials,” she said. “The beauty of the materials is that you can see through the transparent layers: you have that depth. And the gold looks beautiful in candlelight.”

Joe Calderwood, left, and Chris Polson are seen here at their Lincolnville shop, Twin Brooks Stretchers, with stacks of sized and shaped aspen stock behind them and a sampling of stretchers hanging on the wall.

Joe Calderwood, left, and Chris Polson are seen here at their Lincolnville shop, Twin Brooks Stretchers, with stacks of sized and shaped aspen stock behind them and a sampling of stretchers hanging on the wall.

Behind every artist there’s a great canvas

Framer Chris Polson uses a pneumatic nailer to assemble a stretcher.

Deep in the woods of Lincolnville at Twin Brooks Stretchers, owners Chris Polson and Joe Calderwood—the latter’s family roots here date to the 1700s— make frames stretched with blank canvas ready for artists to paint. Although it’s the artists whose images and names become known, the stretchers upon which they paint their works also are the products of painstaking work and talent. Since 1993, Polson and Calderwood have annually produced hundreds for clients around the nation, some of them today’s most prominent artists, people such as Jonathan Borofsky, Alex Katz, and Jamie Wyeth.

Framer Chris Polson uses a pneumatic nailer to assemble a stretcher.

Deep in the woods of Lincolnville at Twin Brooks Stretchers, owners Chris Polson and Joe Calderwood—the latter’s family roots here date to the 1700s— make frames stretched with blank canvas ready for artists to paint. Although it’s the artists whose images and names become known, the stretchers upon which they paint their works also are the products of painstaking work and talent. Since 1993, Polson and Calderwood have annually produced hundreds for clients around the nation, some of them today’s most prominent artists, people such as Jonathan Borofsky, Alex Katz, and Jamie Wyeth.

The process begins with a shipment of Maine-grown aspen logs. Aspen is ideal for art frames because, when properly dried and selected for straightness and structural integrity, it’s a strong, lightweight, stable wood, said Polson. It’s free from sticky pitch and associated staining problems, holds staples or tacks well, and isn’t splintery. It’s also a pioneer species that easily re-colonizes. That’s satisfying from the ecosystem standpoint.

“If we’re going to cut a tree, it’s nice to know a site will be repopulated without necessarily doing a lot of extra work,” said Polson.

The assembled stretcher, consisting of a frame and stretched Belgian linen, is primed with gesso.

The logs are dropped near the yard’s outdoor band saw, where the two men spend six to eight weeks each year sawing up to 1,000 board feet per day in 12-foot lengths. They neatly stack the cut lumber, with spacers between each layer, to allow it to air-dry for a spell; the length of time depends on the time of year. After that, the lumber goes to an oil-fired kiln to complete the seasoning process.

The assembled stretcher, consisting of a frame and stretched Belgian linen, is primed with gesso.

The logs are dropped near the yard’s outdoor band saw, where the two men spend six to eight weeks each year sawing up to 1,000 board feet per day in 12-foot lengths. They neatly stack the cut lumber, with spacers between each layer, to allow it to air-dry for a spell; the length of time depends on the time of year. After that, the lumber goes to an oil-fired kiln to complete the seasoning process.

The dried lumber is then picked up by A.E. Sampson & Son, a Warren-based wood flooring and architectural woodwork company, which has the ripping machines and four-sided planers needed to cut each piece into 4-inch widths and shape the outside perimeters. This stock is milled by Sampson to be 3 inches by 1.25 inches thick on one edge, tapering to 7/8 of an inch on the opposite edge.

Then the pieces go back to Calderwood and Polson, who assemble it into frames, onto which they stretch and staple Belgian linen with hospital-corner-like tucks. Tite-Joint Fasteners allow artists to expand the size of the frame to their preference. The partners produce “a zillion” combinations, in Polson’s words, of length, width, thickness, and even shape. Artists can buy the stretchers completely assembled, or as a kit.

Polson and Calderwood came into the business from different backgrounds. Polson, who was born in Rhode Island, trained in forest management at the University of Michigan and worked in Alaska doing forest research. His family had vacationed in Maine when he was a child, and his wife had family in Maine, so they bought land in Lincolnville and made the move. For a while, he made carousel horses as sculptures, and traditional British rocking horses, but mainly he’s a lifelong landscape oil painter who has produced hundreds of paintings and has had numerous solo and group shows since 1996.

Calderwood was born and raised in Lincolnville, where his family had a sawmill on their dairy farm. He became an expert sawyer. Before meeting Polson, he ran a local mill and cut wood for various lumber outlets and construction companies, as well as individuals.

They met in the early 1990s, when Polson wrote a forest management plan for Calderwood’s property. They soon started making stretchers for local artists. Polson was an early adopter of Internet marketing, which allowed the partners to skip retail and work directly with customers. The business thrived.

Today, they have about 1,500 customers, many of them regulars, around the nation. Polson will occasionally travel for special installations involving large artworks that must be disassembled and reassembled for moves between artist studios and museums or galleries. For one such job, in the Philippines, the Lopez Memorial Museum commissioned a 12-foot by 24-foot stretcher for an existing painting that was going to hang in a building lobby. The partners made the frame, disassembled it, then packed it in a specially built shipping crate. Polson flew over to receive the shipment, reassembled the frame, stretched the painting onto it, and supervised its hanging.

Recent orders include ones for customers in New York City, Ohio, and Massachusetts. Two stretchers are due to a Georgia client who wanted overnight delivery, six kits are for a Denver artist, and 48 primed stretchers are for one of their most prolific clients. The variety and abundance of orders make it clear that the art of painting is alive and well. That’s due, in part, to the talent behind the paintings.

Laurie Schreiber has written for newspapers and magazines on the coast of Maine for more than 25 years.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.