The Revenue Man

Catching smugglers during Prohibition was tough work

Agents remove a cache of liquor from this boat in Portland Harbor, 1920. Photo courtesy Collections of Maine Historical Society/Maine Today Media

Agents remove a cache of liquor from this boat in Portland Harbor, 1920. Photo courtesy Collections of Maine Historical Society/Maine Today Media

In 1919, when the nation adopted a national prohibition law, the U.S. Customs Service—along with the Coast Guard—was charged with stopping liquor smugglers. That same year, Howe Higgins became deputy collector of customs, stationed first in Presque Isle, Maine, and later in Southwest Harbor. He was later appointed Inspector of customs, with his wife, Athol (Kane) Higgins as Deputy Collector.

Being a conscientious man, he took his job seriously: to uphold the prohibition laws and crack down on people who were trying to smuggle illegal rum into the country. This was no easy feat. The new laws had made rum-running a big business.

The Maine coast, with its inlets and secluded harbors, was an ideal spot for smugglers. Foreign vessels loaded with liquor, often pure alcohol in five-gallon tins, would lie to just outside the limits of U.S. waters. Boats would come out from shore to run the liquor in under the cover of darkness, and often fog.

There are many stories about these escapades. One rumrunner had a boat that was known for its loud exhaust during the daytime hours. A Mr. Mitchell of Southwest Harbor asked the boat’s owner to bring him a tin of alcohol. The man told Mitchell to be in a boat by the channel buoy in the Western Way at midnight. Mitchell expected to hear the smuggler’s boat coming, but did not. At the precise time agreed upon, there was a swish of water. A boat appeared out of the fog and went slowly by without a sound. A man held out a tin of alcohol for Mitchell to catch as the boat disappeared silently in the fog without stopping. It seems the exhaust pipe had a valve that, when thrown, diverted the noisy exhaust into mufflers under the water, thereby eliminating sounds that might give the smuggler’s presence away.

Inspector Higgins had no automobile and the customs service only furnished one on a limited basis. His records, from which much of the following is taken, show that he sometimes walked from Southwest Harbor to Somesville and Bar Harbor. He spent many hours on stake-outs at places where he expected liquor to be landed, often staying all night. Besides enforcing the liquor laws he also inspected vessels entering port on legitimate business. Over time, Higgins developed a group of observers who would alert him to suspicious activity.

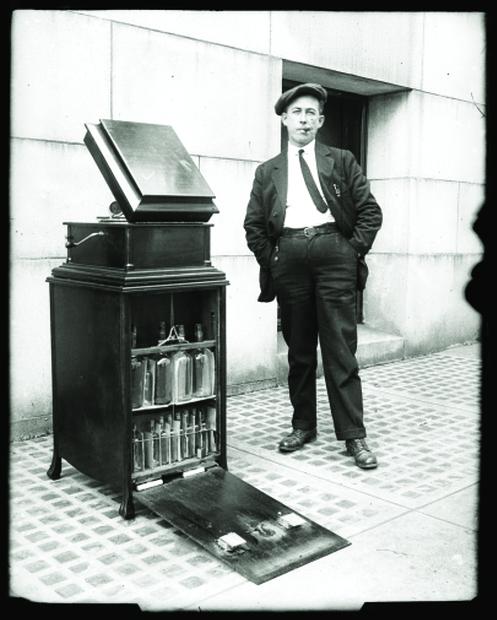

A victrola housed a hidden liquor cabinet, seen here after a Portland bust in 1922. Photo courtesy Collections of Maine Historical Society/Maine Today Media

Many respected people were involved in rum-running, which boosted the local economy. New automobiles were purchased, new boats and new houses were built on Mount Desert Island during the early 1930s at the height of the Great Depression. For example, three fast boats fitted with large airplane engines were built in Southwest Harbor for New York buyers. One was 80 feet long. The assumption is that they were intended to smuggle rum.

A victrola housed a hidden liquor cabinet, seen here after a Portland bust in 1922. Photo courtesy Collections of Maine Historical Society/Maine Today Media

Many respected people were involved in rum-running, which boosted the local economy. New automobiles were purchased, new boats and new houses were built on Mount Desert Island during the early 1930s at the height of the Great Depression. For example, three fast boats fitted with large airplane engines were built in Southwest Harbor for New York buyers. One was 80 feet long. The assumption is that they were intended to smuggle rum.

Estelle Benson Stanley, proprietor of the Stanley House, a popular summer hotel, was at one time president of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. Meanwhile, her sons, Derby and Bierly, were both involved in rum-running. Derby was a highline fisherman and could have made a good living if he had just stuck to fishing. But smuggling was like a game, and the jackpot was huge.

For a time during the 1920s, my father, Chester Stanley, fished with Derby. He asked my father to join him on his rum-running trips and make some big money but my father declined, thinking it too risky.

One time, while working at the Ocean House, an employee was told to bring the hotel’s motorboat to the wharf for some guests who wanted to go fishing. The boat was half full of water and had bullet holes in the sides. He reported this to the lady in charge. “Oh dear!” she said. “Derby used that boat last night.”

The local acceptance of smuggling frustrated Higgins. In March 1924 he notified the Collector of Customs at Portland about a seizure of 12 cases of contraband alcohol that day in Northeast Harbor. Instead of making a case against the individual owners of the liquor that had been seized, Higgins made a case against the storeowners where it was found: “Otis M. Ober and his wife, Josephine Ober, whom I believe to be equally guilty,” he wrote. Local smugglers supplied the liquor to the Obers to distribute to the summer people of Northeast Harbor. It was then brought back to the Ober premises for storage during the winter months, he noted. “Marks indicate that most of this liquor was deposited with the Obers in 1923.” Josephine Ober, known to the summer people of Northeast Harbor as “The Empress Josephine,” was just as guilty as Mr. Ober in supplying the needs of the summer people, Higgins argued.

“I feel that the prosecution of these people will have a very good effect in that particular town, as there is undoubtedly a strong feeling for strict enforcement in Northeast Harbor.”

But while the liquor was not returned, no arrests were ever made.

In 1923, Higgins secured a warrant to search the vault of the Bar Harbor Banking and Trust Co., where he found and seized a sizable amount of liquor belonging to several Bar Harbor summer residents, namely a Miss Coles, Arthur C. Train, Dr. Ludwig Kast, and Mrs. Joseph Pulitzer. However, a judge ruled the liquor was pre-Prohibition, and was being stored in the bank vault for the winter, and ordered the liquor returned to the vault.

In one of his letters, Inspector Higgins wrote that Bar Harbor had more bootleggers and rumrunners than any other town in the county. He listed the names of 36 men, detailing their prior convictions and noting that many had no plans to stop smuggling any time soon. Higgins felt like a wanted man and carried a revolver as it was rumored that the Bar Harbor rumrunners had contracted with someone in Boston to take him out.

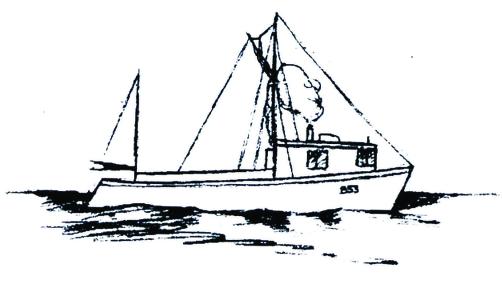

Howe Higgins made this sketch of Beatrice, a motorboat that he suspected to be involved in smuggling operations, and included it in a 1922 letter to the Deputy Collector of Customs. Courtesy Ralph W. Stanley

Taking the scofflaws to court was one thing but securing a conviction was another. Rum-running involved so much money that bribery and corruption were rampant. If a conviction was secured, imposing fines or seizing boats was not a great deterrent. A rumrunner could easily earn enough in one night to more than pay his fine or even buy a new boat.

Howe Higgins made this sketch of Beatrice, a motorboat that he suspected to be involved in smuggling operations, and included it in a 1922 letter to the Deputy Collector of Customs. Courtesy Ralph W. Stanley

Taking the scofflaws to court was one thing but securing a conviction was another. Rum-running involved so much money that bribery and corruption were rampant. If a conviction was secured, imposing fines or seizing boats was not a great deterrent. A rumrunner could easily earn enough in one night to more than pay his fine or even buy a new boat.

Fed up with his inability to obtain convictions for rum smuggling, Higgins resigned from the customs service in 1930.

“I have done more to enforce the laws relating to the unlawful transportation and possession of liquor than any other officer in Hancock County, and possibly more than any other customs officer in Maine,” he wrote in his resignation letter. He cited one incident in 1929, when he seized 250 quarts of assorted liquors, along with a lobster car that contained 3,000 lbs. of legal lobsters and 95 short lobsters.

“At the time I made this seizure, I was told by several citizens that the offender had ‘too many friends’ and would never be prosecuted,” Higgins wrote. “To date this man has not been tried on the illegal possession of liquor, though there were six government witnesses. In other words the Government failed to back me up in my enforcement work.”

He went on in a similar aggrieved vein. “When the various enforcement agencies in this county, Federal, state, and local fail to take any intelligent action toward stopping the estimated 10,000 cases of liquor that are smuggled annually into and through this county, and when the government fails to give me the support in my enforcement work which I feel I have a right to expect, then my interest in a government job ends.”

Higgins concluded that he left the job with a clear conscience that he did his best, “but with very little respect for those enforcement agencies, which are doing practically nothing to enforce the law.”

In 1933, Higgins ran for sheriff of Hancock County on the Socialist ticket and was defeated. Prohibition was repealed in that same year. He later became an artist, starting a cottage industry during the Depression creating plastic souvenirs, including lighthouse paperwieghts and lobster lamps.

Ralph W. Stanley has built more than 70 wooden boats over his career. He lives in Southwest Harbor.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.