The Fixers - Fred Murphy, Waterville's Cobbler

Fine craftsmanship is in demand, now more than ever

By Greg Rössel

Fred Murphy, 30-year veteran Waterville cobbler

Fred Murphy, 30-year veteran Waterville cobbler

and proprietor of Babe’s shoe repair. Photos by Greg Rössel.“With the start of the maple sap run, so come the customers” said Fred Murphy, 30-year veteran Waterville cobbler and proprietor of Babe’s shoe repair. And so they do.

One brought a pair of L.L. Bean boots to have its heel re-stitched. Bill Card traveled all the way from Damariscotta to have three-quarter soles put on his Johnson and Murphy dress shoes. Nice shoes. Said Card “Fred does great work! I buy the best shoes I can afford and have had Fred re-build 4 out last 6 I’ve bought. It’s less wasteful and saves money, too.” Bill is a happy customer and a fortunate one as well to find someone who does this kind of work. Murphy does other leather work too--another fellow in a leather Civil War-style cap came in for a heavy duty custom built holster for a utility tool.

It doesn’t seem that long ago when a cobbler or “orthopedic repair’ shop was a staple in almost any town of size. In such shops there would be gray haired guys with names like Eddie who would put a tag in your shoe and assure you that in no time at all you would be back in business with a new non-slip, triple grip, Cat’s Paw rubber heel, a Neolite sole, or a pair of distinctive sounding taps. Not so anymore. Inexpensive, “throw-away” shoes and a paucity of skilled hands have reduced the number of cobbler shops in the state to around eleven or approximately one for every hundred thousand Mainers. One has to wonder if the shoe industry would be just as glad if the trade went the way of gargoyle carvers and buggy-whip makers. Yet, here on Elm Street in Waterville, Babe’s is doing a thriving business.

The 56-year-old Murphy came to the leather-working trade in a roundabout fashion. After leaving the service in the early 1970s, he did a short stint at a school for nursing, but that didn’t work out. From there began a series of eclectic, self designed apprenticeships with trades people where he would work for room and board for six months at a time.

This vocational odyssey eventually led to the Bucksport/Orland region where he found employment at the h.o.m.e. co-op. (h.o.m.e., founded by Sister Lucy Poulin, started as craft cooperative, and has since expanded to be involved in economic reconstruction and social rehabilitation).

It doesn’t seem that long ago when a cobbler or “orthopedic repair’ shop was a staple in almost any town of size. In such shops there would be gray haired guys with names like Eddie who would put a tag in your shoe and assure you that in no time at all you would be back in business with a new non-slip, triple grip, Cat’s Paw rubber heel, a Neolite sole, or a pair of distinctive sounding taps. Not so anymore. Inexpensive, “throw-away” shoes and a paucity of skilled hands have reduced the number of cobbler shops in the state to around eleven or approximately one for every hundred thousand Mainers. One has to wonder if the shoe industry would be just as glad if the trade went the way of gargoyle carvers and buggy-whip makers. Yet, here on Elm Street in Waterville, Babe’s is doing a thriving business.

The 56-year-old Murphy came to the leather-working trade in a roundabout fashion. After leaving the service in the early 1970s, he did a short stint at a school for nursing, but that didn’t work out. From there began a series of eclectic, self designed apprenticeships with trades people where he would work for room and board for six months at a time.

This vocational odyssey eventually led to the Bucksport/Orland region where he found employment at the h.o.m.e. co-op. (h.o.m.e., founded by Sister Lucy Poulin, started as craft cooperative, and has since expanded to be involved in economic reconstruction and social rehabilitation).

His instructor there was Stanley Grindle, who impressed upon Murphy an appreciation of the dignity and honor of the working trades. H.o.m.e. was an exciting place to be in those days, with a constant flow of progressive visitors like Helen and Scott Nearing and Dorothy Day. Stanley had a shoe repair and leather making shop in Bucksport where Murphy worked for a year, staying in a cabin the woods and living cheaply.

In 1977, Murphy started as an apprentice at a leather shop that specialized in making fine leather bags and clothing in Unity, Maine.

After a year, he came to Waterville. Next to the Smoke Shop, a small shoe repair shop known as Lincoln Shoe Repair was for sale. Murphy purchased the business for $2,500 from two women who were moving to Colorado, took on the $200 monthly shop rent, and changed the name to Harmony Shoe Repair. In the process of cleaning out the store he discovered a backlog of work that brought him $500 in the first two weeks he was open.

He was there for ten years – long enough to build up a loyal trade and start a family. Then came word that Babe’s Shoe repair, just down the road on Elm Street, was for sale. Babe was ready to retire so Murphy bought the business and Babe agreed to stay on for a while. Although it’s many years later, “Some people still think my name is Babe,” said Murphy.

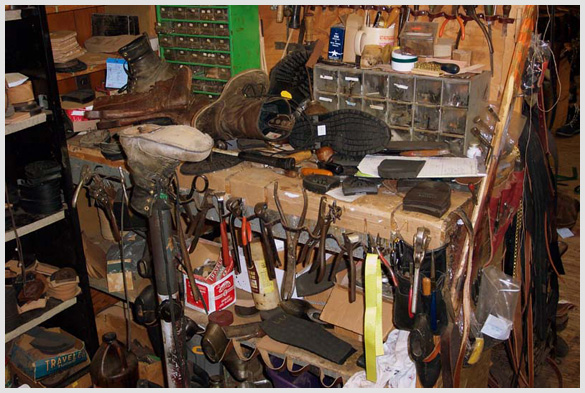

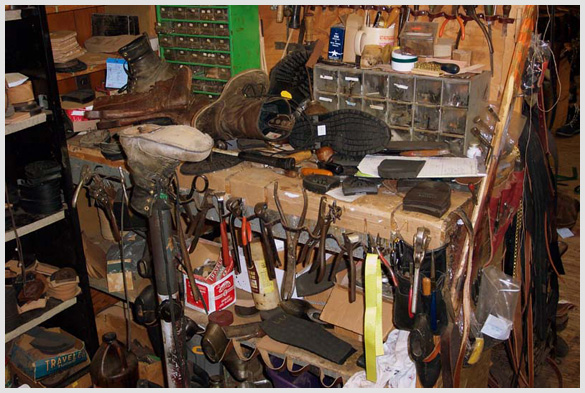

The secret to being a successful cobbler is to be willing to tackle any project. Murphy does custom orthopedics, molded shoes, and designs and builds boots, chaps, and jackets specifically for the needs of his customers.

He told me, “I am always studying why I am doing what I am doing” when creating a product.” It helps too, that Murphy is a bit of a contrarian. He’s willing to tackle “jobs that people say can’t be done.” That was what led to working with heavy material repair and fabrication – leather, plastics, and canvas. On Monday mornings when the store isn’t open (officially), the visitor will find Murphy cranking out industrial contracts like making long face wraps used by metal turners at Mid Maine Machine or building enormous paint brushes that will be used to paint the edges of the chunky “Chinet” paper plates produced by the Huhtamaki factory on the Fairfield side of town.

Interestingly, cobbler’s tools are still available. “You can still get what you need – but it is expensive,” Murphy said. Industrial sewing machines are still being built. But inevitably many of Murphy’s workhorse tools are antiques found in someone’s shed.

His instructor there was Stanley Grindle, who impressed upon Murphy an appreciation of the dignity and honor of the working trades. H.o.m.e. was an exciting place to be in those days, with a constant flow of progressive visitors like Helen and Scott Nearing and Dorothy Day. Stanley had a shoe repair and leather making shop in Bucksport where Murphy worked for a year, staying in a cabin the woods and living cheaply.

In 1977, Murphy started as an apprentice at a leather shop that specialized in making fine leather bags and clothing in Unity, Maine.

After a year, he came to Waterville. Next to the Smoke Shop, a small shoe repair shop known as Lincoln Shoe Repair was for sale. Murphy purchased the business for $2,500 from two women who were moving to Colorado, took on the $200 monthly shop rent, and changed the name to Harmony Shoe Repair. In the process of cleaning out the store he discovered a backlog of work that brought him $500 in the first two weeks he was open.

He was there for ten years – long enough to build up a loyal trade and start a family. Then came word that Babe’s Shoe repair, just down the road on Elm Street, was for sale. Babe was ready to retire so Murphy bought the business and Babe agreed to stay on for a while. Although it’s many years later, “Some people still think my name is Babe,” said Murphy.

The secret to being a successful cobbler is to be willing to tackle any project. Murphy does custom orthopedics, molded shoes, and designs and builds boots, chaps, and jackets specifically for the needs of his customers.

He told me, “I am always studying why I am doing what I am doing” when creating a product.” It helps too, that Murphy is a bit of a contrarian. He’s willing to tackle “jobs that people say can’t be done.” That was what led to working with heavy material repair and fabrication – leather, plastics, and canvas. On Monday mornings when the store isn’t open (officially), the visitor will find Murphy cranking out industrial contracts like making long face wraps used by metal turners at Mid Maine Machine or building enormous paint brushes that will be used to paint the edges of the chunky “Chinet” paper plates produced by the Huhtamaki factory on the Fairfield side of town.

Interestingly, cobbler’s tools are still available. “You can still get what you need – but it is expensive,” Murphy said. Industrial sewing machines are still being built. But inevitably many of Murphy’s workhorse tools are antiques found in someone’s shed.

Murphy notes that his business is probably a reliable economic indicator. “After 9-11, my business spiked as folks were unsure what was going to happen. Recently, it has shown a similar spurt. Repairing things seems again like a good idea.”

The small number of cobblers concerns Murphy, since there is simply more work than can be done by him and his colleagues. For example, when Bangor’s Yankee Shoe Shop burned down, much of that city’s work was referred to Babe’s. Previously he would sew 350 to 400 coat zippers a year. That year, those repairs zipped up to 150 a month.

Statistics on the trade roll easily from Murphy’s tongue. “In 1947 there were 100,000 cobblers in the US, in 1967, there were 21,000, today the estimate is 4,000. There are but 3 schools that each turn out about 20 students a year. They can’t keep up with the demand.” To that end, he takes on students on a regular basis (including the cobbler from the new Bangor Yankee Shoe Shop) and he hopes to start a cobbler school at his 49-acre farm in South China. His students would have a year-long course of study and hands-on work, including keeping the store, as part of their practical internships.

Murphy notes that his business is probably a reliable economic indicator. “After 9-11, my business spiked as folks were unsure what was going to happen. Recently, it has shown a similar spurt. Repairing things seems again like a good idea.”

The small number of cobblers concerns Murphy, since there is simply more work than can be done by him and his colleagues. For example, when Bangor’s Yankee Shoe Shop burned down, much of that city’s work was referred to Babe’s. Previously he would sew 350 to 400 coat zippers a year. That year, those repairs zipped up to 150 a month.

Statistics on the trade roll easily from Murphy’s tongue. “In 1947 there were 100,000 cobblers in the US, in 1967, there were 21,000, today the estimate is 4,000. There are but 3 schools that each turn out about 20 students a year. They can’t keep up with the demand.” To that end, he takes on students on a regular basis (including the cobbler from the new Bangor Yankee Shoe Shop) and he hopes to start a cobbler school at his 49-acre farm in South China. His students would have a year-long course of study and hands-on work, including keeping the store, as part of their practical internships.

Like his mentor, Stanley Grindle, Murphy believes in the value of skilled craftsmanship and hands-on work and despairs at the current short-term thinking that devalues the work of the tradesman and shoddy quantity over quality. To that end, he has recently opened the other half of his building up as a locale where craftspeople can market their wares be they wood, metal, bone, or fabric.

Reflecting on his 30 years in the trade, Murphy is philosophical “I have reached the stage that I am a good cobbler – I want to be an excellent one.”

Babe's Shoe Repair

40 Elm St.

Waterville, ME 04901

207-873-1355

www.shoerepairer.com

Like his mentor, Stanley Grindle, Murphy believes in the value of skilled craftsmanship and hands-on work and despairs at the current short-term thinking that devalues the work of the tradesman and shoddy quantity over quality. To that end, he has recently opened the other half of his building up as a locale where craftspeople can market their wares be they wood, metal, bone, or fabric.

Reflecting on his 30 years in the trade, Murphy is philosophical “I have reached the stage that I am a good cobbler – I want to be an excellent one.”

Babe's Shoe Repair

40 Elm St.

Waterville, ME 04901

207-873-1355

www.shoerepairer.com

Fred Murphy, 30-year veteran Waterville cobbler

Fred Murphy, 30-year veteran Waterville cobbler and proprietor of Babe’s shoe repair. Photos by Greg Rössel.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.